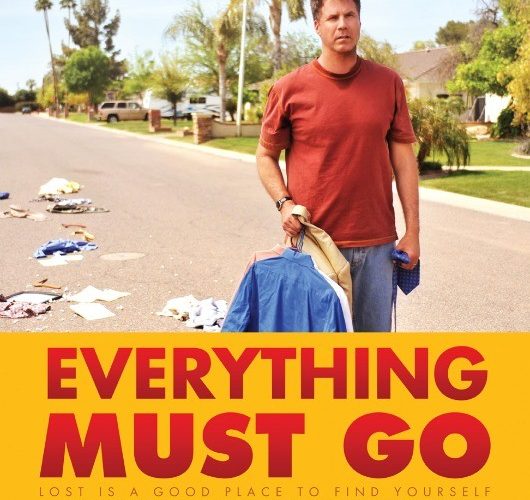

Like Will Ferrell’s last dramatic turn Stranger Than Fiction, Everything Must Go is a bittersweet tale of an Everyman’s redemption with the curly-haired comedian in the role of flailing antihero. Sadly, despite a few moments of well-captured tenderness, Everything is ultimately a bland affair.

Based on Raymond Carver’s short story “Why Don’t You Dance?” Everything centers on Nick Hasley, a man who loses his home, job, car, savings, wife, cell phone, and dignity before the film hits the ten-minute mark. He’s an alcoholic struggling to get sober while begrudgingly living on his front lawn after his estranged wife locked him out of their home. Now, Nick has three days to pull himself together before he’ll be dragged off to jail for vagrancy. While festering in his yard surrounded by his discarded material possessions, Nick strikes up an unlikely friendship with a sweet latchkey kid named Kenny (Christopher Jordan Wallace) as well as an unwieldy flirtation with his new neighbor, a pregnant beauty played by Rebecca Hall. These two intensely indie creations cajole Nick into change that includes an emotionally charged yard sale. It’s a tale of losing everything and finding yourself, and in concept it’s beautiful, simple, even poetic. Sadly, in this execution it flounders, due to first-time director Dan Rush’s unsteady hand.

Ferrell, who proved poignant and compelling in Stranger Than Fiction, offers an uneven performance here that veers from oddly endearing to limp. Michael Pena, who plays his friend/AA sponsor, is so dead-eyed and lifeless in his performance that it’s hard to feel the two have any connection, leaving a third act twist to fall flat rather than prove dramatic. Hall, who dazzled in Vicky Cristina Barcelona, fizzles here, where Rush’s direction repeatedly results in forced dramatic turns. Even exemplary character actor Stephen Root is wasted in a small and cartoonish role as a neighbor/bully.

While the film does offer some beautiful examples of visual storytelling, it lacks nuance overall, coming off amateurish and ham-fisted. The performances lack development, but it’s difficult to blame the actors as the story itself abandons several plot lines, including the budding bond between Nick and Kenny. Rush splinters the focus of his hero’s journey, making it hard to follow which is to be the path of his salvation: the friendship with a boy who (despite Nick’s obvious character flaws) looks up to him? Making amends with his wronged wife? Selling off his things, and thereby freeing him from his troubled past? A romance with his married and pregnant neighbor? Or a reconnection with an old high school crush played with a beautiful effortlessness by Laura Dern? So many half-pursued ventures leads to a meandering narrative that slows to a crawl as Nick staggers along. And it’s a shame, because like it’s protagonist – there is something great at the film’s core: a tale of a man forced to rebuild his sense of self after all its signifiers have been stripped away. Some moments shine, like those between Ferrell and Wallace, and certain delicate dialogues between Ferrell and Hall, but overall Everything proves too much for Rush to handle, shamefully leaving its characters’ arcs to fall away as collateral damage.