Martin Scorsese made one of the first English-language (and one of the very first American) pushes for Hong Sang-soo by recording an introduction for the South Korean helmer’s fifth feature, Woman Is the Future of Man. The video is brief, but he amply described Hong’s perpetually mysterious, endlessly inventive eye and ear for narrative construction by quoting Manny Farber’s words on Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope: “Hong Sang-soo’s pictures unpeel like an orange.” These films are populated by familiar constructs — the two leads are often a man and a woman; the man is usually a narrow-minded dork who’s traveling through a new land and always uncomfortable, particularly within the vicinity of the woman he inevitably likes — and its scenes consist of everyday activity: drinking, walking, conversation — often ending as the man reveals himself a selfish, creepy, and / or pathetic dope — and, in his earlier films, lots of sex. In other words, they’d sound massively uninteresting if described on a point-by-point basis. But when his patient visual style and narrative form — one built on exclusion as much as inclusion — begin working their usual spell, it seems unquestionable that he’s one of our greatest living filmmakers.

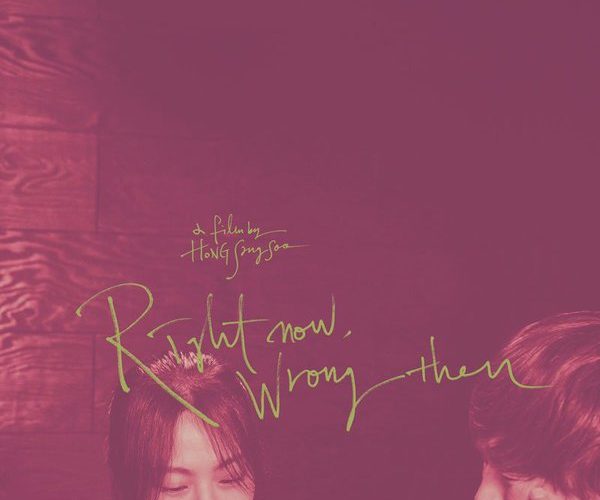

Right Now, Wrong Then is a terrific example of Hong’s talents, which means it also sounds massively uninteresting: visiting an unknown city to present a screening of his film, a director, Ham Cheon-soo (Jeong Jay-yeong) meets a woman, Yoon Hee-jeong (Kim Min-hee), who he immediately takes a liking to. They go to her house, where she shows him a painting of hers and the conversation highlights personal interests; they go out for coffee and tea, where the conversation is mostly surface-based; they go out for sushi and Soju, where the conversation reveals intense personal pain; they go to her friend’s house, where the conversation shifts in some way that makes Yoon distressed — Hong’s trademark zoom isolates during a critical moment in the conversation between Ham and the friends; a catalyst is inferred, but not laid out in any exact terms — and causes her to cut the evening short; she goes home. The next day, Ham attends his screening, makes a few bizarrely angry remarks about being an artist, castigates the moderator outside — “So shameless and ignorant! How can he be a critic?” — and leaves.

And then the opening title card reappears, but what was initially referred to as Right Then, Wrong Now becomes Right Now, Wrong Then. What we saw is more or less happening again, but, for whatever reason — perhaps something, in so many words, mystical, given the prevalence of Buddha, their meeting at a Buddhist temple called The Blessing Hall, and the meditative, sleep-like state preceding each meeting would further indicate as much — progressing in a different key: Ham is saying other, better things, and Yoon thus responds in a more emphatic, open sense. While there’s the impression that every event that’s previously occurred has replayed, entirely new sequences emerge from Ham and Yoon’s improved interaction.

Because the new tenor of conversation sometimes reverses person-to-person power dynamics — itself an additional form of revelation — this second look doesn’t reshape character profiles; it simply expands them. The first Yoon’s vague ambivalence and discomfort is (potentially) explained by the second Yoon’s revelation of a poor mother-father relationship — by all means a standard character detail, yet one that here blossoms into a practically unheard-of legitimacy because of the unheard-of context under which it is revealed. Soon enough, it’s impossible to tell how or why a scenario might change in its second run through, and the fun of it — because this is a very fun, funny movie, no matter the embarrassment or ugliness of the emotions — is a mental back-and-forth game with no clear end point.

All of that’s a lot of space to describe single-shot dialogues, I know, but Right Now, Wrong Then is so deeply invested in this, and mines so much from this — mines so much thorough means I’ve never even seen a film attempt — that it’s sometimes hard to talk about anything else. The simple lack of a proper exposition makes it one of Hong’s more mysterious pictures. What does it mean when we see one aspect of a conversation the first time, only to have simple editing completely excise it during a second run through? Is it unnecessary because some decisions and emotional registers are so set in stone by the kind of people we already are?

Through this, Right Now, Wrong Then stands among his most immediately relatable endeavors. To say nothing of Hong’s ear for believable, layered dialogue and his intelligent eye for conversation — playing out in single shots gives them a thoroughly lifelike pace that’s then dramatically highlighted by a use of isolating zooms — running through the first-this-now-that process may cause audiences to reflect back on their own foolishness. Whether or not Ham realizes it, he’s living out the ultimate in wish-fulfillment. Who hasn’t mishandled a conversation and soon run through a scenario where the right thing is said? Hindsight is always 20/20, and this film’s clarity eventually emerges from our own connection to the larger emotional truth of a scene, a line, a gesture, or a pause, all of which seem calculated from the outset and only accumulate in significance the deeper we go.

It speaks to Hong’s near-uniform excellence that, all this prostrating about the central conceit’s effects notwithstanding, Right Now, Wrong Then is perhaps his weakest film since 2010’s Hahaha. (There have been six since then. The Day He Arrives manipulates the perception of time and emotional registers to stand among the decade’s greatest works, and few films in recent memory are as conceptually playful or structurally tight as his previous feature, the still-undistributed Hill of Freedom.) Knowing how it’s all to proceed, the first section was marked by a certain tedium — the anticipation of what’s to follow. More than that, though, it’s worth asking if the two-sided structure is conceived and written in favor of the moments we’re inevitably forced to reconsider — in other terms, if what we’re watching is, emotional honesty and keen observations aside, mostly rooted in the quality of being set-up.

But if hindsight is 20/20, the final effect of a work this knotty is far and away the most significant to even speak of. In building a mystery, comedy, romance, occasional melodrama, and even a study of the artist’s foolishness that defies expectations well after we’re familiar with its brilliant conceit, Hong has yet again proven the vitality of his voice. At this point, it seems unlikely he’ll ever make a bad film.

Right Now, Wrong Then plated at TIFF and opens on June 24.