There’s ease to idolizing the IRA for rising against their British oppressors because the number of Irish descendants retaining a piece of nationalism at heart is huge. Movies deify them, bartenders make “Irish Car Bombs”, and the group remains in existence still hoping for the Irish Republic they proclaimed in 1916. To some the revolution and subsequent civil war were fought by heroes. To others the IRA is nothing more than terrorists. Either way, there’s substance to the effort that keeps it in our consciousness as something to know about and choose a side in no matter how seriously we care. We don’t do the same for Quebec, though. No, they’re merely “brats” to revile and accuse of wanting too much in their willingness to break-up a country for “freedom” from a life that already is.

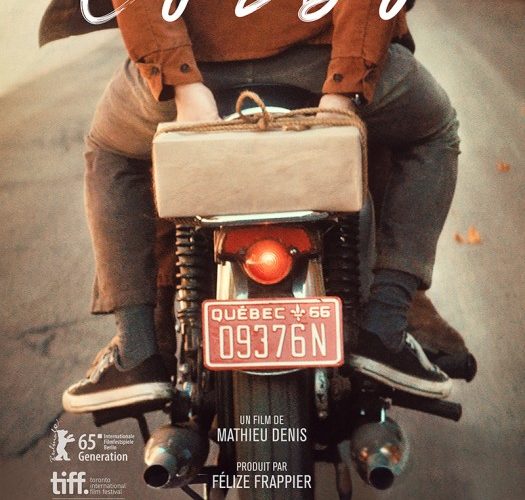

I make this comparison because Mathieu Denis‘ solo directorial debut Corbo—portraying a few months in 1966 when the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) was ratcheting up their violent protests en route to the infamous October Crisis in 1970—reminded me so much of the Irish Civil War-centered The Wind That Shakes the Barley. Both are beautifully shot, brilliantly acted, and unfold at a gradual pace to increase the emotionality and tragedy befalling those involved. Neither looks to construct a hero either, instead showing us the depressing truth that even the “winners” ultimately prove losers in the end. Yes the drive for independence is admirable and the fight these young souls possess inspiring, but at a certain point the anger and rhetoric do become indoctrination as activists lose their way into all-out terrorism.

Despite Montreal being only a six-hour drive from my hometown of Buffalo, I know absolutely nothing about its history or its desire to become an independent state other than joke. The aforementioned October Crisis got so bad that the Canadian government utilized the War Measures Act for only the third time in its history—the other two being WWI and WWII—instating a quasi-martial law to scoop up the FLQ and end their destructive ways. It’s said the violence this group of extremists wrought actually galvanized the Provence of Quebec’s efforts to be political rather than militant. Where they hoped they would instill a hunger in the Québécois to join their ranks and drive out the Anglo colonizers, the FLQ ultimately drove support towards sounder minds unwilling to murder senselessly.

Denis’ film seeks to explain why people would join in the first place at a time of defeat for the Rassemblement pour l’Indépendance Nationale (RIN) through a family with multiple allegiances and a history of oppression. Born wanting nothing to a lawyer who worked hard to reach his status in the community, both Jean Corbo (Anthony Therrien) and his brother Claude (Jean-François Pronovost) can’t help but idealistically want their nation to be run by French speakers with French Canadian rights paramount. Their father (Tony Nardi) sees such ideas as an affront to what he’s built—a life Quebec has afforded him despite the horror of an internment camp stint in the 40s due to his Italian descent. Whereas Claude embraces argument and politics to one day see nationalization, though, Jean impatiently desires action.

Based on true events, we witness this sixteen-year old boy turn rebellious against his father into the life of a willing participant of bombings and murder. Like all teenage boys there was of course a girl involved (Karelle Tremblay‘s Jules), but not quite like you’d think. Sure there were feelings, but Denis never allows love or lust to become a reason for what Jean does. While she gets him to read a copy of the FLQ leaflet The Axe, it was the words he read that mobilized him into action. From foot soldiers like Jules and François (Antoine L’Ecuyer) he meets generals in Jacques (Simon Pigeon) and Alain (Maxime Mailloux). From there it’s their FLQ wannabe leader Mathieu (Francis Ducharme), a man not much older than the rest and yet completely on-board with the innocent blood on his hands.

Just as Jean learns the FLQ way via secret meetings concerning inferiority complex, colonization, and political radical Frantz Fanon’s teachings that violence is the only way to regain even footing with your oppressors, so do we. Parallels between family life and the movement subtly inject themselves into the proceedings and we eventually understand Jean’s reasoning for diving into the fight goes beyond Quebec. He seeks a place to belong—something he’s never felt in his bourgeois neighborhood or private schools full of teachers who’d rather say nothing than admit crimes against humanity that haven’t “officially” been rendered as history yet. The FLQ gives his frustration an outlet, friends, and equals. He is Marius from Les Mis only the violence here isn’t quite as just. Yet even when he knows this to be true, there’s no turning back.

Corbo therefore proves a telling look into how easy it is to lose your way no matter how righteous the cause. It shows us the clinical precision of the FLQ’s utilitarianism, the yearning on behalf of Quebec’s youth to make a difference, and the guilt-ravaged souls unable to reconcile their morality with their beliefs. We can see ourselves in Therrien’s depiction of Jean—scared, lost, and angry. But there’s more in the grief and second-guessing of Tremblay, Pigeon, and especially L’Ecuver breaking our hearts. Because at a certain point tragedy mounts so high that escape is impossible. To leave would mean all they’ve lost was in vain. The only way to honor those who sacrificed themselves to the cause is victory despite knowing the price is too high. At the end of the day, one innocent death is one too many.

Corbo is playing TIFF as part of the Discovery program. See our complete coverage below and a clip above.