There are surely few sweeter delights in this troubling world of ours than seeing Willem Dafoe politely escort a group of storks off a motel driveway. It is, perhaps, the best of a number of striking visual flourishes in Sean Baker’s The Florida Project, an aesthetically rich but narratively slight film that sees the writer-director (along with cinematographer Alexis Zabe) switch from the saturated and much-celebrated iPhone camerawork utilized for his last film Tangerine to the crackle and unmistakable warmth of celluloid.

Indeed, it proves a perfect tool for capturing the bizarre imitation-Disney hotels in which the film plays out, but could it be too beautiful for its own good? Baker indulges just a little too much time shooting his young hyperactive actors in off-key locations and perhaps not enough on their character development or narrative arcs.

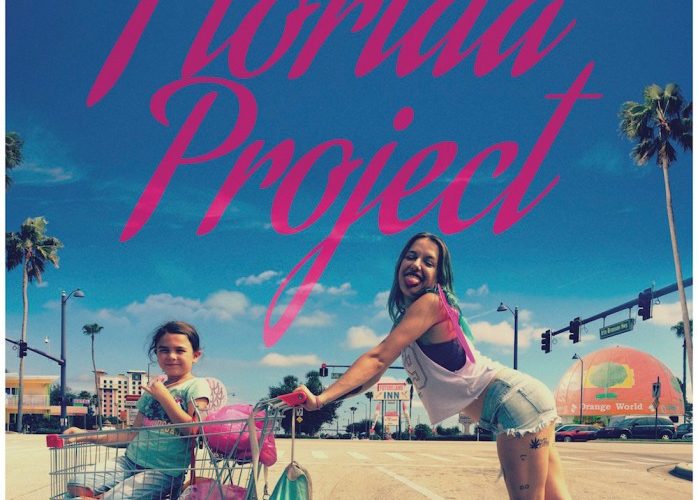

Newcomers Brooklynn Prince and Bria Vinaite play Moonee and Halley, respectively, a 6-year-old live wire and her young mother who live in an obscenely purple hotel called Magic Castle in the tourist-heavy district just south of the Magic Kingdom resort in Orlando. Her friend Jancey (Valeria Cotto) lives down the road in another motel called Futureland. The names are not without their ironies. The Florida Project opens to the beat of Kool & the Gang’s classic hit “Celebration,” a wry wink to the once Disney-owned town of that same name where Moonee and her friends cause much of their havoc.

The trio of Moonee, her downstairs neighbor Scooty (Christopher Rivera), and Jancey spend their days covering Jancey’s mother’s car in spit; hustling tourists for tips; eating whatever ice cream they can get their hands on and, on one occasion, accidentally burning down a foreclosed house. Indeed, Baker’s film runs off that very havoc but it’s primarily concerned with how it contrasts with Halley’s adult life (an intergenerational theme that recalls Baker’s earlier film Starlet). Moonee is forced to join her mother as she hustles tourists, selling discount perfumes, and even asked to stay quiet in the bathroom as Halley entertains her clients. Moonee’s obliviousness to the various semi-legal situations is basic exploitation and we’re offered little reason to sympathize with her out of work mom.

Indeed, this struggle can feel like real life at times so it’s a shame that no apparent effort has been made by the director to give the viewer cause to empathize. Halley is crass; unapologetic; selfish; a terrible mother; a bad friend; the list goes on. Moonee, of course, takes after her. What’s more, the motel manager Bobby (Dafoe), whose son wants nothing to do with him, feels responsible for their well-being and repeatedly puts his neck out to save them, even if he’s never thanked for it. The resulting lack of any connection with the film’s supposed protagonists is the Achilles’ heel of The Florida Project, and you might just find yourself rooting for the child protection services when they finally arrive.

All that said, however, there appears to be deeper things at work here, even if they aren’t fully realized. The fact that Halley and Moonee are almost literally living in the shadow of Mega-Corp (in the form of the Mouse House) — almost living off its scraps at times — is a strong visual metaphor for the nation’s staggering wealth divide. The burning down of the foreclosed house also leans towards contemporary concerns but neither diversion is ever truly explored. Indeed, there is certainly a great film in there somewhere, it’s just a shame that the The Florida Project never quite compensates for those fundamental inadequacies.

The Florida Project premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and opens on October 6. See our coverage below.