For our final year-end feature, we’re providing a cumulative look at our favorite films of 2013 here at The Film Stage. Over the last few days a variety of contributors have published their personal top 10 lists, resulting in over 75 films being mentioned, and we’ve pared it down to an even 50. To calculate the list we gave 10 points to everyone’s #1 pick, 9 points to their #2 pick, and so forth, with a half a point going to honorable mentions — in the case of a tie, the film that placed higher on a respective list was given the nod. So, without further ado, check out our last rundown of 2013 below, our complete year-end coverage here, and return in the coming weeks as we look towards 2014.

Contributors (click each name for their top 10 list): Raffi Asdourian, Nathan Bartlebaugh, Forrest Cardamenis, John Fink, Bill Graham, Danny King, Dan Mecca, Nick Newman, Jordan Raup, Christopher Schobert, and Ethan Vestby.

50. The Past (Asghar Farhadi)

Should we forget the past in order to better our future? This existential question is at the core of The Past, Asghar Farhadi‘s follow-up film to the Oscar-winning Iranian film A Separation. Strikingly similar in tone, The Past deals with a trio of characters all groping with personal problems that interconnect in sometimes unpredictable ways. This unfolding drama plays out like a soap opera in terms of the details resting inside each character’s relationship and personal dilemma, yet the material is elevated by Farhadi’s carefully nuanced direction, allowing performances to take center stage. The end result is an effective examination of how past lives can sometimes dictate future selves. – Raffi A.

49. The Bling Ring (Sofia Coppola)

Arriving after her most abstract work, Somewhere, Sofia Coppola’s The Bling Ring is a darkly comedic send-up of reality TV and the culture of Twitter (which creates the illusion you can be BFFs with Paris Hilton or Lindsay Lohan). Starring Emma Watson as the ringleader’s co-hort and Leslie Mann as her mom (who eggs them on with “vision boards”), The Bling Ring perfectly captures (to a literal extent, figuring in the late Harris Savides‘ gorgeous, final work) an American subculture gone too far. – John F.

48. Blancanieves (Pablo Berger)

Pablo Berger’s Blancanieves may be a silent film in form and function, but the delivery method is more than a fashionable gimmick. Berger adorns his bewitching black and white fairy tale with the kind of alluring, direct poetry that cinematic descendants Luis Buñuel and Jean Cocteau specialized in and the result is a fantasy masterpiece as transporting as their best. Spain may take over for enchanted English forests, Snow White has become a matador, her stepmother a withering dominatrix, and the dwarves diminutive circus bullfighters but the mystery and magic of the original tale is magnified here in a true feast for the senses. If you’ve tired of contrived big-budget wonder, seek out Blancanieves and watch it cast its formidable spell. – Nathan B.

47. At Any Price (Ramin Bahrani)

After floating around the 2012-2013 festival circuit, this Sony Classics release should have made director Ramin Bahrani a household name, but At Any Price remains a remarkable American indie that sadly failed to find an audience. Starring Zac Efron as a free spirited racecar driver who rejects his family business, an agriculture supply and farm in crisis, Dennis Quaid plays the patriarch of the family, squeezed under investigation for his seed practices. Co-starring Kim Dickens, Heather Graham and Clancy Brown, At Any Price is a family drama-thriller that offers up a fascinating and entertaining look at modern agriculture. – John F.

46. The Place Beyond the Pines (Derek Cianfrance)

Here is an epic American crime drama, one that takes a narrow-eyed look at class, and how the circumstances of our birth dictate the rest of our lives. It’s boldly told, ambitiously plotted, and often verges on collapse. But Derek Cianfrance and his cast keep it together. Ryan Gosling has never been better as a motorcycle daredevil turned bank robber, Bradley Cooper is nicely flawed as the beat cop who finds himself on Gosling’s tale, and Eva Mendes gives her best performance as the woman who gave birth to Gosling’s child, but knows he’s on the road to nowhere. Few films this year matched this one’s verve and ambition. – Christopher S.

45. The Counselor (Ridley Scott)

One of the most entertaining movies of the year, Ridley Scott’s collaboration with writer Cormac McCarthy marks a brave, creative and ambitious Hollywood film featuring some of the strangest turns from some of the most well-known faces in the game. McCarthy’s script is as cold and cynical as they come. It’s also one of the funniest movies of the year, the kind of comedy that’ll loop in hell. – Dan M.

44. Laurence Anyways (Xavier Dolan)

Having not seen any of Xavier Dolan‘s previous work, I wasn’t sure the best starting point would be his third film, a three-hour drama that was little-seen in the United States. However, I’m glad I snuck it before the end of the year, as Laurence Anyways proved to be one of my favorite films of the year. Tracking the ten-year relationship between Laurence Alia (Melvil Poupaud) and Fred Belair (Suzanne Clément), Dolan’s film explodes with passion and color, perhaps the best ode to French New Wave in recent cinema. – Jordan R.

43. The World’s End (Edgar Wright)

What initially presents itself as a (slightly) dark comedy about bar-hopping evolves, scene by scene, into something satisfyingly ambitious and devastating. It’s an even greater accomplishment when taken in proper context: while sticking the landing on a trilogy initiated by Shaun of the Dead and continued with Hot Fuzz — very possibly the 21st century’s two great comedies — is no easy task, to simply rest on one’s earned laurels has proved as common an option for cappers. Full credit must be paid, then, to director / co-writer Edgar Wright and co-writer / star Simon Pegg for concluding with bared hearts, subverting what we’d expect of their science fiction turn by using homage as a direct means of addressing a deeply, terribly sad tale of addictions, personal failures, and the scars of lives only half-lived. Featuring extended bar fights with extraterrestrial robots, mind. – Nick N.

42. Drug War (Johnnie To)

This rock-hard procedural hits you in the mouth and leaves you bleeding for the duration of its runtime. Flashes of To’s comedy work can be glimpsed here and there (the HaHa character, for instance), but the powerhouse intensity is the dominant force. The cocaine/ice-bath sequence can stand toe-to-toe with any of the year’s other most immaculate set-pieces, while the climactic shootout is a peerless orchestration of sound, space, clarity, and cinematic balance. Even better than this film is the realization that I’ve still got, oh, over 40 other Johnnie To films left to see. – Danny K.

41. Borgman (Alex van Warmerdam)

The less you know about Borgman, the better. All that matters is that it’s Dutch, it was the most bizarre film to play in the main competition of Cannes this year and it’s coming out next year courtesy of Drafthouse Films. Oh, and it’s a devilishly good time for fans of black comedy shenanigans. If any of that sounds at all intriguing, then definitely seek this film out and you’ll be sure to be both bewildered and delighted. All that’s left to say is: Gotta go Borgman. – Raffi A.

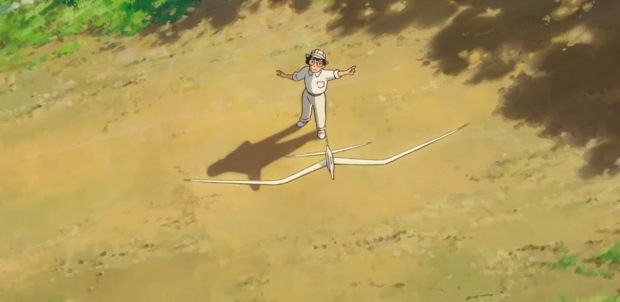

40. The Wind Rises (Hayao Miyazaki)

While I don’t consider myself a Hayao Miyazaki superfan, I’ve enjoyed his animation, but always felt at a distance to his work. With his final feature, The Wind Rises, the director loses the fantastical elements his career has been built upon (aside from a few dream sequences) and the result is an emotional connection I’ve rarely felt in the field of animation. Tracking the life passions of Jirō Horikoshi, a man best known for designing the Zero Fighter plane used in bombing Pearl Harbor, the film deals with obsession, guilt, and loss more effectively than any live-action film I’ve seen this year. Unfortunately, if you missed its one-week run in NY/LA this fall, you’ll have to wait until a home release to screen it with its native Japanese with subtitles, as Disney’s February release will be dubbed. – Jordan R.

39. Ginger and Rosa (Sally Potter)

There were a number of strong coming-of-age dramas this year (the aforementioned Something In The Air, Mud, purportedly The Spectacular Now, and even The Bling Ring), but none fused the creation of period details with a direct script as well as Ginger and Rosa. Director Sally Potter gets a career-best performance out of the always-improving Elle Fanning, and her use of costumes gives us all the backstory we need. The films move from one brilliantly observed moment to another (as when the two girls read magazines and shrink their jeans, of when Rosa takes Ginger to a club), and a great cast of adults add distinct supporting characters to the mix that amplify Ginger’s confusion. – Forrest C.

38. Norte, the End of History (Lav Diaz)

It’d be nice to discuss Lav Diaz’s latest without mentioning its runtime; four hours and ten minutes, which while reasonably short by his standards, will still likely scare off even a number of adventurous cinephiles. Yet the passage of time comes inevitable in actually engaging with it, as it’s intentionally most felt in the film’s strongest passage, in which its narrative strands stop at their seeming rigorous narrative and thematic development to simply depict life occurring at its own pace. Of course, considering the apocalypse it ultimately reaches, in which good and evil; a wrongfully torn-apart peasant family for the former, an existentially corrupted law student the latter, don’t see just ends, it comes easier to understand the film’s ultimate virtue; it’s lack of obsession with racing to its own ideological conclusions. – Ethan V.

37. The Grandmaster (Wong Kar-wai)

I was rather fond of The Grandmaster’s theatrical form, finding both majesty and irrepressible beauty throughout the supposedly “dumbed-down” iteration of what was once a longer, knottier international item. The memory of an American release still relatively fresh in my mind, visiting Wong Kar-wai’s homeland edition proved a startling experience — not necessarily in viewing some exponential improvement on that which was already strong, but in encountering an entirely different narrative that befits a more resonant, true-to-the-auteur examination of time’s unstoppable force and its tragic shaping of romantic fates. (The year’s finest action sequences — the train-platform fight stands out, but Tony Leung‘s blank-faced “one more kick” is the stuff of dreams — certainly do no harm to my appreciation.) While one may wish to seek out the 130-minute cut in lieu of The Weinstein Company’s outing — I’ve felt it necessary to make a distinction between those two, after all — in either form does Wong provide a ravishing, formally radical work that refuses to be dismissed. – Nick N.

36. Spring Breakers (Harmony Korine)

Harmony Korine‘s bizarre trip to Florida feels like the cinematic equivalent of taking drugs. Featuring dizzying cinematography from the lens of Benoît Debie, the DP of Gaspar Noe‘s Enter the Void and Irreversible, the film is less a traditional narrative and more a fever dream that encapsulates, similarly to The Wolf of Wall Street, the escapism inherent in the American Dream. But where Scorsese is more interested in the dangerous potential of unfettered freedom, Korine is all about embracing it. Spring Breakers is a hallucinatory journey into the vices of American culture without trying to tackle any one them too seriously, it’s just an odd amalgamation of a film. – Raffi A.

35. Passion (Brian De Palma)

In interviews for his comeback film, Passion, Brian De Palma stated his disdain for shooting on digital, its lack of ability to properly light beautiful women standing as the chief reason. The irony, of course, is that laptop screens and surveillance cameras were seemingly present at every point of the film, often capturing his leading ladies in bizarre, unflattering compositions that render them as concrete objects of the mise-en-scène. This is perhaps why adjectives that are all essentially variations on each other have been constantly thrown Passion’s way: “ridiculous,” “campy,” or, even more likely, “laughable” — though, to me, the right one might just be “brazen.” This isn’t just patting Mr. De Palma’s ever-present self-awareness on the back, but rather pointing out that, behind the smirk, there lies a genuine questioning of images themselves. – Ethan V.

34. Blue Jasmine (Woody Allen)

Woody Allen‘s finest drama since Crimes and Misdemeanors was a dark, unsettling character study centered around one of the finest performances the director has ever brought to the screen. Months later, it is easy to forget how frantically unhinged Cate Blanchett‘s woman-on-the-verge of a lead actually is; rewatching at home may, if anything, make Blanchett, and the film itself, even stronger. – Christopher S.

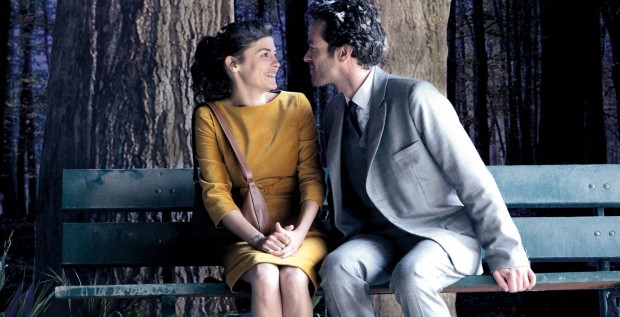

33. Mood Indigo (Michel Gondry)

There is an absolute whimsy to Michel Gondry‘s Mood Indigo and it becomes infectious. If you’re familiar with Gondry’s previous works, you might understand what it means when I say this is his film without restraint. Every piece of the world seems to be alive with vivid color or animated in ways you wouldn’t expect. But the story is, at times, absurd.. I felt like I was actually Alice in Wonderland while watching Mood Indigo; at times I even wondered if I was dreaming. To experience this in a theater was transformative because I was absolutely engrossed. But that’s when things change, and the story becomes something else entirely. The whimsy of the world is like a shiny, freshly painted veneer that covers the darkness just underneath. In this world, there are also weapons, sickness, death, and depression. They aren’t nearly as fun to look at, and sometimes downright devastating against the backdrop of the whimsical world of Colin. When we are in love, everything seems right with the world. But the world keeps living, and there is darkness all around us as well. Mood Indigo, as an experience, is one I’ll never be able to shake—because of the whimsy, yes, but also because of the way that can become dulled without the color we are used to. – Bill G.

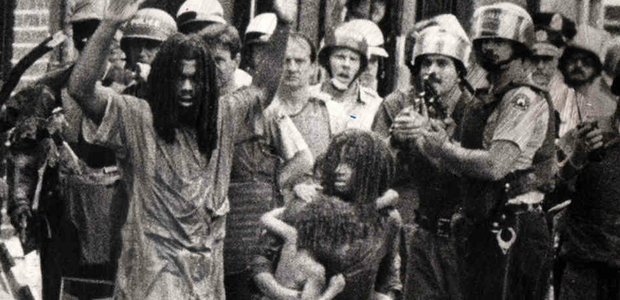

32. Let the Fire Burn (Jason Osder)

Let the Fire Burn tells the incendiary story of multiple bad decisions made by the City of Philadelphia which lead to the destruction of a densely populated neighborhood in attempt to “evict” the extremist African American liberation group MOVE. Told entirely in archival footage, Osder masterfully captures time and place; we know exactly what was known then, as muddy as the facts are. Framed by testimonials given before a commission investigating the day, the chips fall where they will. A powerful, thrilling, engaging and essential documentary, it’s fresh, speaking to us in the present tense from 1985. – John F.

31. Everyday (Michael Winterbottom)

This small miracle of a film concerns a young father in jail desperately trying to keep his family together. Director Michael Winterbottom gets raw, personal performances from everyone on screen, the film never coping to tearjerker moments or manipulative narrative turns. Of all of the films on this list, this is one you haven’t heard of, which is why it should be the one you go out and see. – Dan M.

30. Like Someone in Love (Abbas Kiarostami)

On their own, the first three sequences of Kiarostami’s Certified Copy follow-up—the long conversation in the Tokyo bar, the infinite-voicemail nighttime cab ride, the initial meeting between Rin Takanashi and Tadashi Okuno—comprise some of the best pure filmmaking of the year. The chemistry between what’s on-screen and the space and sound that’s lurking just beyond the frame is irresistibly playful and, often (as in the cab sequence), profoundly sad. Far from diluting his auteur value, Kiarostami’s ventures outside his native Iran have solidified the universal resonance of his thematic interests and inimitable formalism. – Danny K.

29. Fruitvale Station (Ryan Coogler)

What could have been an exploitative look at an instance of police brutality and the unfathomable outcome wrought from fear and abuse of authority in an incident more complex than simple racial undertones might describe, writer/director Ryan Coogler’s Fruitvale Station decides instead to show how integral each life on this earth is to those he/she loves. It isn’t about vilifying the white murderer or turning the black victim into a hero; it’s about showing the life of a complicated man with faults and a checkered past finally understanding what matters above selfish wants and desires. And with some of the year’s best performances—Michael B. Jordan, Octavia Spencer, Melonie Diaz—we’re made to understand both the good and bad results of our actions and that things are never as cut and dry as we’d like to believe. – Jared M.

28. Jealousy (Philippe Garrel)

Due to the constant influence May ’68 has on his work, Philippe Garrel’s films often concern a fruitless pursuit of something lost — and, with Jealousy, maybe the simplest human concept: happiness, is the object of this typically talky trek. Amidst the festival circuit’s plentiful offerings of bloat, whether through glibly provocative subject matter or tired recycling of arthouse aesthetics, the relaxed 77 minutes comes as not only a relief, but a reminder of the power found in simple expressiveness. The best way to say it is that Jealousy feels like a story told only through the very images it requires, the multiple perspectives drawing from Garrel’s own life as a father, lover, and child all made wholly clear. – Ethan V.

27. Finishers (Nils Tavernier)

Finishers is a wonderful, crowd-pleasing tearjerker, inspired by the real life Hoyt Family. Starring Fabien Heraud as Julien, a 17-year old with congenital palsy, he gravitates towards his mother (Alexandra Lamy) while his relationship with his father Paul (Jacques Gamblin) has remained distant. After several attempts, Julien convinces Paul to carry him on his back for the grueling Iron Man France triathlon. Packing a physical and emotional punch, Finishers (currently without a US distributor) is a first-rate family sports drama that left not a dry eye in the house when it premiered at TIFF. – John F.

26. The Hunt (Thomas Vinterberg)

Premiering at Cannes Film Festival back in 2012, Thomas Vinterberg‘s The Hunt received a minor theatrical release this past summer. A gripping character study exploring what can happen when one lie spreads throughout a small community, Mads Mikkelsen delivers his finest performance in this harrowing drama. With a final sequence that still haunts my mind, The Hunt is one of the most powerful films of the year. – Jordan R.

25. The Great Gatsby (Baz Luhrmann)

As grand as they come, Baz Luhrmann’s sweeping adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic novel is perhaps the sloppiest film to ever grace a year-end best-of list. When it misses (ill-advised bookends) it misses by a mile, but when it hits (DiCaprio’s Gatsby, that party scene, that music along with much else) it hits the bullseye. – Dan M.

24. Wadjda (Haifaa al-Mansour)

Haifaa al-Mansour’s Wadjda is a small miracle of a film. The first Saudi Arabian feature directed by a woman, it’s a humorous but tremendously moving story, both universal in its larger themes and microcosmic when it comes to observing the lives of females within the male-dominated culture. The subversion is subtle, excluding the men from its inner circle of characters, while focusing on one of the community’s youngest, Wadjda, a little girl whose big act of rebellion is that she wants to buy and ride a bicycle. At first glance, the observational style of the film recalls fables like Bicycle Thieves and the Iranian gem Children of Heaven, but Mansour rises to the occasion of her film and makes it stand on its own as a sensitive and joyful portrait of these women. She shepherds an amazing child performance from Waad Mohammed, and through breathtaking compositions, generously turns the camera towards her female brethren, letting their lives speak for themselves. – Nathan B.

23. Nebraska (Alexander Payne)

Alexander Payne’s latest feature is his best, a wonderful film that does so much right from its unique tone (shifting quietly from parody to melancholy) and its relationships. The story is centered around the life of Woody Grant (Bruce Dern, in a brilliant performance) and potentially his alternative life as he returns to rural Nebraska on his way to claim a prize. Enabling the stubborn old Woody is his son David (Will Forte), a lonely stereo salesman. June Squibb also gives a hilarious performance as Woody’s wife. Nebraska is a rough, yet lovable movie, hitting notes so rarely seen. It is one of the best road comedies ever made, embodying the old notion that road movies are about the journey, not the destination. Here is a film that reflects on journey in truly profound and often heartbreaking ways. – John F.

22. American Hustle (David O. Russell)

David O. Russell’s latest success has been brushed off as “Scorsese-lite” in some circles, but that’s a silly, baseless criticism. In fact, American Hustle feels as wonderfully free-form as Soderbergh or Altman, a character study more interested in mise-en-scene and dramatic fakery than plot. Christian Bale, Amy Adams, Bradley Cooper, and, especially, Jennifer Lawrence have never had such meaty parts, and all have never been stronger. It’s a glorious high, and one can imagine Russell smirking on the sidelines, as exhilarated as we are. – Christopher S.

21. Short Term 12 (Destin Cretton)

There are two bookend moments in Destin Cretton’s Short Term 12 that highlight this warm yet hard-hitting indie drama’s immense appeal. In both, John Gallagher’s shaggy, likable Mason is regaling his fellow foster home workers with colorful anecdotes from his tenure, each sunny myth interrupted by the reality of the job. Cretton, once a foster care worker, has much of Mason in him, illuminating the power of what a shared hug, hand on the shoulder, or simple impromptu birthday card may do for those who feel rudderless and alone. For all of that, he’s also got a quality that Mason, and his pregnant girlfriend Grace (Brie Larson), the real focus of Term, learn along the way; that the harsh reality of life is just as integral to our journey’s meaning as the brighter moments. Term is filled with brilliant performances, undeniable truths and an unwavering—and yes, brave—belief that there’s boldness in optimism and sophistication in unconditional kindness. – Nathan B.

20. Gravity (Alfonso Cuarón)

I don’t watch many films again — let alone in theaters, four different times, with four different sets of friends or family, all in 3D — but Gravity was a special case. Director Alfonso Cuarón has crafted the modern blockbuster masterpiece. It’s entirely engaging on a surface level, with the terror of space and its infinite vastness alongside the unpredictability of orbit that can become predictable chaos (just set your watch to it). But Cuarón has clearly enjoyed infusing the film with themes of religion, evolution, and more. – Bill G.

19. You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet (Alain Resnais)

A twilight masterpiece that gleefully eschews old-man reflection and nostalgia, and through expertly deployed digital cinematography instead strives to contribute toward a future its own maker only has so much time left to see. While the meta-cinematic gambit is best discovered for oneself, narrative (even this, [technically] one of the most studied in human history) is of less importance than the act of observing faces and voices that have shaped generations of cinephilia. I’m immensely glad to know Alain Resnais has one more film premiering in only a couple of months’ time, but, for all intents and purposes, You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet is a final statement par excellence. – Nick N.

18. Stories We Tell (Sarah Polley)

Sarah Polley’s Stories We Tell, the actor-director’s documentary exploration of her family and lineage, is one of the finest works about family and memory in recent years. Yet it’s a difficult film to discuss, as every detail seems like a spoiler. I noticed, in the time between the film’s TIFF 2012 premiere and my seeing it, that almost every review or piece about the film referenced “spoilers” or included a “spoiler alert.” I found that rather obnoxious, but now I see why that was so important. There are unforgettable moments throughout, including one that left me confused, breathless, and exhilarated, and that is the feeling that has lingered for me. Even discussing what Polley is actually up to here as a storyteller feels like a reveal, and that makes for an incredible cinematic experience. – Chris S.

17. Ain’t Them Bodies Saints (David Lowery)

Another love story—there appears to be a trend here—David Lowery’s subtle and quiet portrait has a tad more dysfunction than the rest considering the crimes we witness Rooney Mara and Casey Affleck commit before she’s made to raise their daughter alone while he serves a stint in jail. Stunning cinematographer and a sure hand from the director paint this 1970s-era Meridian, TX landscape with complexity and danger as an undissolvable love risks ripping them apart when the distance proves too much for Affleck’s Bob to simply take laying down. A brilliant character study wherein every person on screen is faced with a hard choice resonating beyond the law, Ain’t Them Bodies Saints is a gorgeously bittersweet romance where survival is forever intertwined with tragedy. – Jared M.

16. Closed Curtain (Jafar Panahi)

I can’t say much more now than I did in my full review, but Jafar Panahi’s Closed Curtain is a thrilling meditation on—literally—the liberating powers of cinema, an exploration of where hope comes from, and a chilling cry for help. What begins as a fiction slowly reveals itself to be a visualization of one filmmaker’s creative process, as well as a more fleshed out exploration of what constitutes a film and how digital technology can impact filmmaking that Panahi examined in his previous work, This Is Not A Film. That this one still doesn’t have a distribution deal is a travesty. – Forrest C.

15. Frances Ha (Noah Baumbach)

There’s a sequence about thirty minutes into Noah Baumbach’s Frances Ha that captures a feeling of real joy. Frances, played by Greta Gerwig, runs down the street, twirling, leaping, and smiling, in a Carax-appropriating scene set to David Bowie’s “Modern Love.” The sequence seems, well, perfect, and in some ways, so is Frances Ha. It’s a simple, funny, moving story that captures the experience of drifting through your twenties, growing apart from friends, and discovering who you are as well as any film I’ve ever seen. A perfect film? It sure feels that way. – Christopher S.

14. At Berkeley (Frederick Wiseman)

A rich, behind-the-scenes look at academia, Fredrick Wiseman studies his largest institution yet while barely scratching the surface. Berkeley is a challenging subject, a laboratory of many issues percolating in higher education, however, administrators interested in transparency give Wiseman tremendous access. Each scene never overstays its welcome as the film captures many fascinating moments from the bottom up. Juxtaposing administrators crafting a public safety and PR response to a planned protest, with a classroom where freshman undergraduates struggle to define their roles in society, At Berkeley, the 38th institution-centered documentary by Wiseman, is not only one of his best, but his most accessible, despite its four-hour running time. – John F.

13. Stray Dogs (Tsai Ming-liang)

Presumably Tsai Ming-liang‘s final feature, Stray Dogs appropriately sees slow-cinema, an art film “movement” of which he’s considered one of the defining members, at its most extreme. With shots lasting around ten minutes in length — and, more often than not, displaying acts ranging from mundane to outright inactive; in particular, an extended “climax” that’s simply two people looking at a mural — the film could easily be described as “difficult.” Yet while it becomes an even trickier narrative piece by the final third, venturing into the obtuse (or as my interpretation sees it, the afterlife), the film’s emotions are always crystal clear. Tsai’s form doesn’t adhere to the tenets of stylized realism with some distancing anthropology, but displays an intimacy of character, setting, and, above all, time. No wonder we come to look at two still figures as a living, breathing version of the very mural they’re turned to tears by. – Ethan V.

12. Blue is the Warmest Color (Abdellatif Kechiche)

When this film premiered at Cannes earlier this year, it caught most festival audiences off guard by the raw emotion and heartfelt performances from it’s two leads Adèle Exarchopoulos and Léa Seydoux. It’s for good reason as well, since watching the electric chemistry between these two actors makes for one of the most exhilarating and draining love stories in years. Director Abdellatif Kechiche elegantly captures the various movements in the symphony of an emotional relationship, from the initial spark to the sweeping swell of carnal pleasure before disintegrating into a sea of heartbreak and sadness. Despite all the controversy post-release, Blue is the Warmest Color remains one of the most emotionally resonant testaments to the beauty and pain of falling in and out of love. – Raffi A.

11. To the Wonder (Terrence Malick)

The incalculable sorrow conjured by To the Wonder is evinced in a four-word line scribbled by Darren Hughes: “Where’s all the shit?” That this is Malick’s first fully contemporary film isn’t just some vague piece of intrigue or juicy bit of trivia for auteurist die-hards—it’s the absolute essence of what makes the film impossible to dismiss. Malick and DP Emmanuel Lubezki’s view of the contemporary world (particularly, that of suburban America) is so foreign and alien that it’s hardly comparable to anything else, even despite the technique’s fervent similarity to that of the other films in Malick’s 2000s period. Olga Kurylenko (in one of the year’s most luminous performances), Ben Affleck, Rachel McAdams, Javier Bardem—to see these people roam around in 1950s Texas or in The New World would be one thing (a poetic revision of history/memory, an aesthetic rendering of a bygone era, etc.); to see them do it in Oklahoma in 2012, in empty houses and barren streets, is strange, paranormal, beautiful, kind of fucked-up, and definitely unforgettable. – Danny K.

10. Leviathan (Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel)

Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel could have earned a position for no more than the transcendent ballet between underwater gliding and soaring seagulls — a show-stopping sequence that forced yours truly to elicit something as awestruck as “oh my God” several times over a few minutes — but, even as a moment of overwhelming beauty, it’s only a portion placed amidst the most natural (yet entirely foreign) images captured this decade. I have a strong distaste for considerations of “game-changing” cinema — a strong distaste for anything that claims to forecast the medium’s future, really — but Leviathan, a first-person view equal-parts terrifying and ethereal, tests that personal preference to extreme degrees in promising a previously unthinkable terrain for documentary and experimental cinema. I can’t wait to see what follows. – Nick N.

9. Her (Spike Jonze)

I expected a lot of things from Spike Jonze’s quirky tale of an emotionally vulnerable man dating his computer, but what I wasn’t prepared for was just how gently accurate it is when dealing with the reality of human relationships, both on small, personal levels and at larger social ones too. Without ever really stopping to explain exactly how this near future operates, or what the parameters of its technology actually are, we are dropped into Theodore’s (Joaquin Phoenix) life and made to feel the loneliness and vulnerability while expressing our own wonder at new wrinkles in this reality. Phoenix gives one of his finest and sure to be most underrated performances as a guy who is trying to recover from a broken heart while learning that he’s not nearly as connected to others as he expected. Awards or no, Scarlett Johansson is astonishing in what she accomplishes with only voice-work. Samantha, the operating system that nabs Theo’s heart, is an original and compelling creation and Jonze does her justice by structuring his film around the various evolving stages of her awareness. This is a brilliant and complex tale about the future of our technology, a spiritual exploration about what makes us tick as humans in the act of being. – Nathan B.

8. A Touch of Sin (Jia Zhangke)

Jia Zhangke’s films often depict an easy overlap between politics and pop culture, whether it be the entertainers of Platform or The World, or the seeming overabundance of accessibility in Unknown Pleasures. This certainly holds true for A Touch of Sin, which — while loosely based on four real stories of violence fuelled by capitalism in contemporary China — plays with the tropes of past popular cinema as many characters come to embody modern Wuxia knights, the brandishing of Zhao Tao’s knife easily recalling the heightened sword strokes of King Hu. But as a public opera of one these classic Wuxia stories directly poses at the end, “Do you understand your sin?” As easy as it may sometimes prove to cheer on these acts of violence, every one comes with their own set of repercussions. – Ethan V.

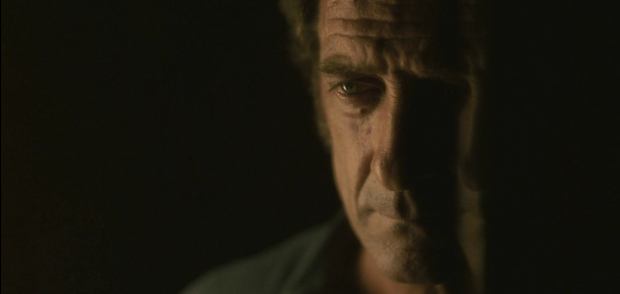

7. Bastards (Claire Denis)

Modern-to-the-hilt noir submerged in the unforgiving blackness of digital photography, emotional currents sparked with a tactile cinema appealing directly to the senses. In retrospect, it (sometimes) seems these two edges could sufficiently define Claire Denis’s Bastards, but her films can never be boiled down to a few descriptors — which might be a tinge ironic, given the immense power of a narrative system that consists of absolutely no more than each crucial component, like a cinematic razor blade slicing its way through all that’s pure. The crescendo would prove unbearable if the pleasures weren’t so extreme, and Bastards’s final moments are the most viscerally shocking of 2013: just as the final piece is about to snap in, the roving, low-resolution images dart away from an act of savagery — not for the sake of respite, but only as a promise that cycles of violence, corruption, and systematic failure are bound to continue. As Tindersticks carry into the end credits, we’re left with no choice but to embrace the darkness. – Nick N.

6. The Act Of Killing (Joshua Oppenheimer and Anonymous)

The most affecting documentary to come out in some time, Joshua Oppenheimer’s film puts a very real and very frightening face on evil. Here we are introduced to the monsters we’ve been afraid of our whole life, and it is impossible to look away. – Dan M.

5. Inside Llewyn Davis (Ethan Coen, Joel Coen)

Take out True Grit, which I still haven’t come around to, and the recent run of the Coen brothers—No Country for Old Men, Burn After Reading, A Serious Man, Inside Llewyn Davis—is as spotless as anything in American narrative cinema right now. The new film is an indelible portrait of an artist who’s both musically talented and professionally doomed. When Oscar Isaac sings “Hang Me, Oh Hang Me” in the opening scene, into the smoky residue of the Gaslight Café circa 1961, it’s a performance I’d pay good money to see in person. And yet, when Isaac’s later, equally moving rendition of “The Death of Queen Jane” is met with devastating financial skepticism by F. Murray Abraham’s Bud Grossman (“I don’t see a lot of money here”), we don’t bat an eye. That these two things—crystal-clear talent and terminal obscurity—are intertwined so flawlessly into Llewyn’s scenario is some kind of miracle of performance, tone, and worldview. The movie rejects easy nostalgia for the Greenwich Village folk-music scene and instead presents the trade as arduous, stark manual labor—an endless cycle of songs, deals, feuds, junkies, cargo, cats, cars, and couches. – Danny K.

4. Upstream Color (Shane Carruth)

Easily 2013’s most original film, Upstream Color combined the year’s best editing and sound design to create the most transcendent cinematic experience in quite some time. 10 years after Primer, a sci-fi film that was more concerned with being a mindbender than utilizing cinema’s natural language, Shane Carruth has moved forward by leaps and bounds, proving that he is fully aware how disparate elements, from sound to color to editing, can operate individually and/or together to craft an utterly unique and meaningful viewing experience. Trying to give a plot of even thematic summary of Upstream Color in a few short sentences is a fool’s errand, so in lieu of attempting to do so, I’ll simply say that you should watch it. Now. – Forrest C.

3. Before Midnight (Richard Linklater)

As I exited a Sundance Film Festival screening of Before Midnight this past January, I knew it would be hard for another film to match up in the eleven-plus months to follow. And indeed, even after a rewatch, this trilogy-capper is the finest film of 2013. Departing from the dreamlike mood of first (and renewed) love of Before Sunrise and Sunset, but retaining their deceivingly brilliant dialogue, Richard Linklater‘s Before Midnight takes an honest, difficult look at the realities of marriage. If the trio decide to return in 2022, I’ll be waiting with open arms, but if not, they’ve created one of the finest trilogies cinema has to offer. – Jordan R.

2. The Wolf of Wall Street (Martin Scorsese)

The debate over Martin Scorsese’s masterpiece already feels tired. No, The Wolf of Wall Street does not glamorize the antics of Jordan Belfort. But it does revel in them, just like the bloodsuckers who loved him. Leonardo DiCaprio gives his best performance as one of cinema’s great irredeemable assholes, a Quaalude-popping destroyer who, in some ways, feels like the ultimate American businessman. When Wolf finally comes to a close, at nearly the three-hour-marker, this feeling crystallizes. We watch a post-prison Belfort work his magic to a new group of wannabes, and as Scorsese’s camera lingers on their wide-eyed expressions, realize why this film, the director’s later-period classic, is so important: because it captures the allure of money and power in a manner that feels fresh, vital, and now. Everyone involved — Scorsese, DiCaprio, Jonah Hill, Thelma Schoonmaker — are at the top of their game. And the result is a film that will feel as relevant in 20 years as Goodfellas does today. What filmgoer could have hoped for more? – Chris S.

1. 12 Years a Slave (Steve McQueen)

It may have evolved into the “safe choice” for movie of the year, but 12 Years a Slave remains the one that I seem to compare all others to ever since seeing it this fall. Steve McQueen is at the top of his game getting amazing performances from Chiwetel Ejiofor, Michael Fassbender, Lupita Nyong’o, and a ton of recognizable faces from start to finish; orchestrating unsettling scenes such as falsely enslaved Solomon Northrup hanging from a tree by his neck in an excruciatingly long take; and meticulously ensuring that the look and feel of the era comes through in all its brutal injustice. People say it’s excessive, but it’s merely authentic. This is the pain and suffering far too many have forgotten. This is our nation’s darkest day, uncensored and in your face, no longer ignored but seen for its blight on our history as “land of the free.” – Jared M.

What’s your favorite film of 2013?