What is it to spend 15 months in a room with—let’s just speculate—the most influential filmmaker of all-time on his final project, a work for which they did not survive to elaborate upon and left in a forever-obsessed-over state? The man who could answer this question is Nigel Galt. As far as I could tell from a Zoom call, however, Galt is not the shadowy figure some would surely expect of Stanley Kubrick’s key collaborator on Eyes Wide Shut, but—fitting for a movie that yields new connections, intonations, meanings, and possibilities (logical or otherwise) from each viewing—30 minutes hardly felt like enough time, each comment spring-loaded with significant insight.

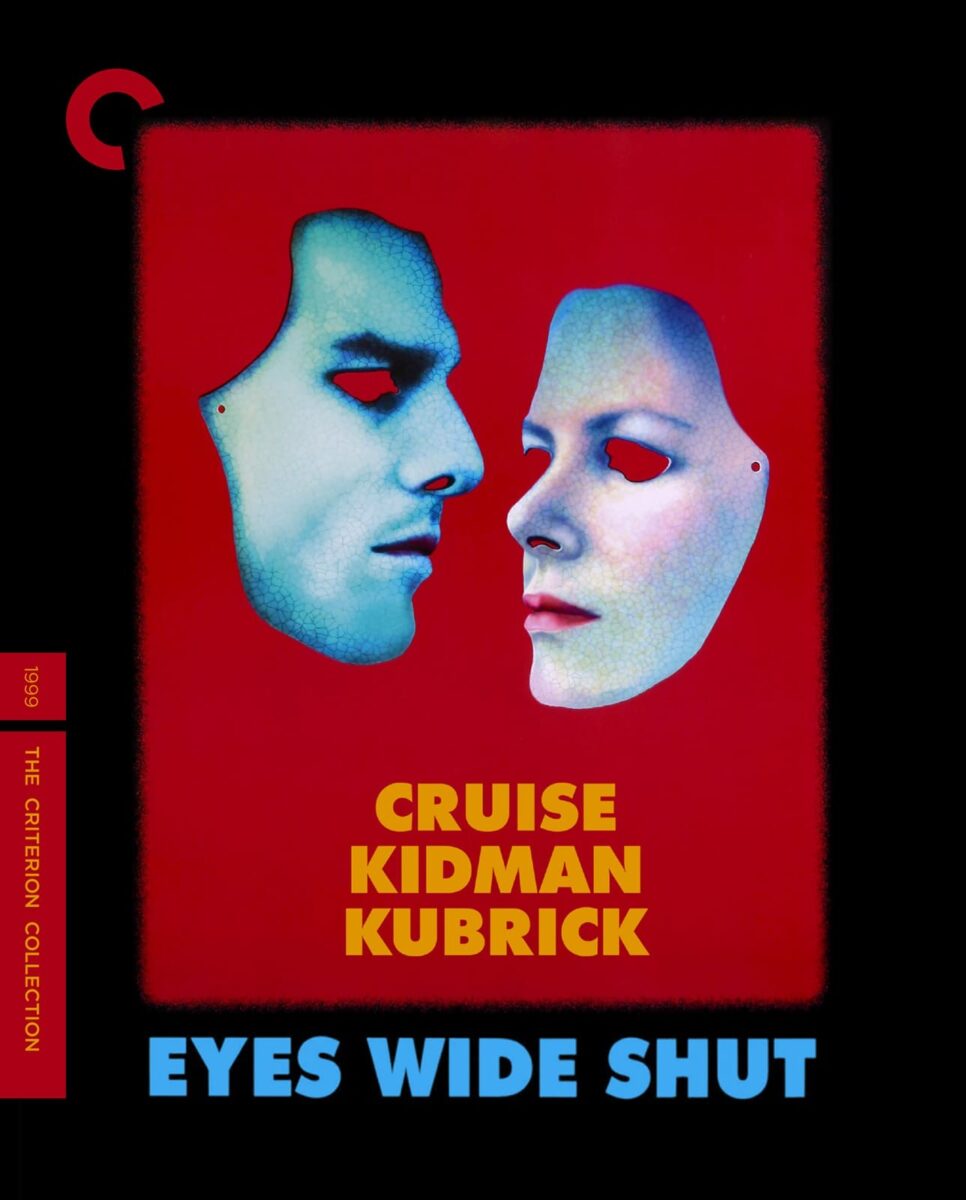

Galt spoke to me on the occasion of Criterion’s 4K UHD release of Eyes Wide Shut, which has already engendered some controversy for a color grade that isn’t quite in keeping with most people’s reference (a 2007 Blu-ray) but, to my eyes, is nearly hypnotic, and directly transposed memories of seeing the film on 35mm just last year. Galt consulted on Eyes‘ initial sound mix and color grade, and seems pleased by the opportunity afforded to cinematographer Larry Smith on this release. But that’s just one strand of our conversation, presented in full below.

The Film Stage: I rewatched the film this weekend on Criterion’s new disc.

Nigel Galt: I haven’t actually seen it yet. It’s arrived, but I haven’t seen it.

Since you worked on an initial color grade, I’d be very curious to hear what you think, because I saw a 35mm print of it last year, and I think this makes a fantastic approximation.

That’s rewarding to know. I haven’t seen a print for a long time.

I programmed one in New York, and for as often as it shows, it was still almost sold-out. It’s a movie that people are just coming out to, I think, because it always grows and metastasizes on each viewing.

Well, I was on it for three years. Because I was on it for the beginning of shooting—or before the beginning of shooting.

I imagine you hold certain secrets to Eyes Wide Shut, or you understand things about it that nobody else does. And I wanted to talk to you about that a little bit.

Yeah, sure.

It wasn’t your first experience with Kubrick.

Yeah, I worked on Full Metal. That’s how I met him—as a sound editor. That’s how I started with him.

Robert P. Kolker and Nathan Abrams’ Kubrick biography says you were on the film as early as December of 1996.

Yeah, we started shooting in the middle of November. I started on the film in the middle of October because we were doing lens tests and stuff like that. Stanley had this process of shooting endless lens tests which were made into slides, and then he would look at them on a slide projector to… we tested something like 70 lenses—this is standard Stanley procedure [Laughs] when picking a film—and whittled that down to the primes and variables that he liked and that were correct. So yeah: I was on from the very beginning to the very end.

Nigel Galt

It’s known that he would do so many takes; it’s said that he would demand a lot from actors. The same biography claims that, towards the deadline for presenting Eyes, you were in there for as much as 17 hours a day.

Pretty much. Stanley lived on New York time when he wasn’t shooting. We never saw him before midday, so my working day was midday to midnight. Seven days a week.

Well, thank you for your service.

[Laughs] That’s all right. I knew what I was in for.

I wonder if there was a habit in the editing room of gravitating towards the more recent take? Did you always have a sense of where to go with that? Or were you still watching everything?

What you have to realize—or what you have to appreciate—with Stanley is that if he wasn’t present, nothing happened. Stanley’s process was completely methodical. And no: we looked at everything. At a million-and-a-half feet of film or something [Laughs] and the only advantage we had on Eyes was that Avid was established or becoming established by then. So we didn’t cut on film. Full Metal was obviously cut on film. Although they used a system called the montage system, which is a tape-based system which they did the basic edit on, and then did the final cut on film. But on Eyes, we did it all on Avid, and he had an elaborate process by which the assistants had to collate all the material. But we looked at everything. I mean, Stanley cut in scene order—always. So scene one was the first thing that was cut. He didn’t go, “I want to cut this scene. I want to do that scene because this is so important.” He never deviated from his process, which always helped. It made it more strenuous at times.

And yes: he shot a huge amount of material. But if he shot 60 takes, we looked at take one and we looked at take 60 and all the ones in between. And it was a process of whittling down—particularly when you came to the intense dialogue scenes. That’s when it started to get interesting. Because with Avid—which is a nightmare for the assistants—he could have every single line in the film broken down into a sequence so that he could see: if you had 60 takes of a set-up or 50 takes, you could have 50 readings of the line in sequence and listen to them.

So the process with him was very much wanting to see everything, know everything, and then we whittled it down. And I can honestly say, as his editor, I learned more about the filmmaking process with Stanley than with anyone else I’ve been working with. I’ve been in business for over 50 years as an assistant editor and I worked with some great editors and directors, but Stanley was the supreme teacher—only because his perspective and mine were very much in tune of how filmmaking should be.

And so then, if you take a scene like the bedroom scene after the party when they come back from the party and get stoned and have… well, for me, it’s the catalyst of the entire film. That scene is a film in itself. That took a long time to cut because we had, we call it, an A/B setup when she sits down, and there were a lot of takes. Stanley tended to do what’s known as “rolling resets” in the camera because he didn’t want to stop and start the camera—because he always said it risks more scratching on the negative—so he would shoot the whole thousand feet and just do rolling resets, so you’d get halfway through the take and he’d say, “Go back to this line and start again.” And so it also made the process of looking at all the material quite complex, because you would have multiple readings of the same line in the same take. But this was his way of how he gets what he gets out of actors. And then, you know, the process of editing becomes one of a… it’s like digging for gold, I guess. [Laughs] It’s the best way to describe it.

But it’s a fascinating process because he always believed that editing was the most important part of filmmaking. He said, “This is why we shoot this stuff: so we can make it work in the cutting room.” And I’ve always believed editing is… not diminished with new technology, but its process has been devalued, I think. Because of the way people edit films. I hate most films I see because they’re brutally cut. [Laughs] Shots that are too short, you know—you just don’t have a chance to register them. This is determined to be “more exciting.”

Previous Blu-ray edition [left] and new Criterion Collection restoration [right]

In different takes and different iterations, was there anything you remember being significantly novel about performance style or visual rhythm? You might be among the few who’ve seen Harvey Keitel’s scenes, some of which had been shot.

There was only one scene we shot with Harvey—that was all that was done. That was unfortunate circumstances. It becomes complex. It was more to do with the person who played his wife, that everything got turned on its head because she made an exposé story to the Sun newspaper about supposedly being groped on set.

Oh.

And so it’s… it’s complex with Harvey.

Okay.

I mean, I think people take it the wrong way or interpret it the wrong way. It didn’t have anything to do with his performance.

Interesting. I didn’t know that. But in general: with Cruise, Kidman, Alan Cumming—whoever—do you remember things being different about certain approaches to the character and the material between take four and take 29?

Oh, yeah. Stanley treated everything as, you know, “This is another part of the process of construction.” So every scene, he was set about them in different ways, but he was magnificent with artists—he was so patient—and I think he drove them mad because he sometimes would not be able to convey specifically what he wanted them to do; he just wanted them to do something that caught his eye. He wanted to be the one to be surprised, you know, by what they did. Because it was an evolutionary process; every day was an evolutionary process in making the film. Nothing was cast in stone in his head. I don’t think he ever thought that way. He wasn’t that kind of person; he wasn’t that rigid. I think there’s one thing I’ll just say about Stanley and that.

Yeah, please.

I always remember seeing some of the documentary footage of a Full Metal Jacket documentary that never got finished, but I think it’s in Life in Pictures, and it’s Joker coming in when Pyle is about to shoot him. And he’s walking in through the door and you hear the directing cues going on and Matthew [Modine] saying, “Well, what do you want me to do, Stanley?” Because it’s obviously the 50th time he’s walked through the door. [Laughs] And he said, “I don’t know, Matthew—just do something different.” And I think that seems flippant on the surface, but he’s looking for something that he hasn’t seen—that’s all it is—and I think that was very much his way when he was directing: he’s looking for the unexpected. I think that’s what makes him unique in many ways. Because he had time. That was the thing he bought himself, the greatest luxury he bought himself: time.

Previous Blu-ray edition [left] and new Criterion Collection restoration [right]

Something that gives Eyes Wide Shut its long-lasting effect is that, of course, Kubrick passed away before it released, so he never talked about it, what he meant by it.

No, absolutely.

And it’s sort of been established—at least in that biography—that he had wanted to do select interviews when the film was going to come out.

I doubt that.

Well, that’s the thing: it’s great that you say this, because that’s just one legend that persists.

Oh, I mean, there’s a lot of myths. And it is myth.

A lot of your process with Kubrick was of a very literal, technical, “go back here, cut here, orient yourself towards here.” In the time you spent together, I wonder if there were ever longer discussions about certain deeper meanings.

I mean, when you sit in a room for 15 months with the same guy every day, you have discussions about all sorts of things. And not always about the film, you know, because you want a distraction. But inherently, the process of editing in itself is subjective to both people—both the editor and the director while they’re doing it. But there’s only one director. So the editor is totally objective to the director’s desires and wishes. But you sit there with your own subjective feelings because it can’t be any other way, and it’s not for me to tell Stanley how to cut the film.

He would ask my feelings all the time, and I think I mentioned this when I did the Paris Kubrick exhibition, in the Q&A: the other thing he did when we were editing—which probably seems obvious when you see his films now—we listen to the same piece of music, basically, for 15 months while we were editing, because that’s where he got his tempo from. He chose a piece of music that he found at the beginning and decided, “This is the rhythm or tempo I want to use. So when I’m watching things back, this is in the background and I can use it as my common metre.” And when I found this fascinating—apart from the fact I constantly tried to hide the CD [Laughs] because I got so fed up with it. Especially as it was a composer I didn’t like. I refuse to name the composer out of decency to them.

Oh, I was going to ask if this was Shostakovich music.

No, no, no. It wasn’t a classic—it was a film composer.

I see.

So, as he’s alive and well, it would be unfair to castigate or label him. [Laughs]

Magnanimous of you.

Yeah, well, I try to be.

Previous Blu-ray edition [left] and new Criterion Collection restoration [right]

But were there certain things that he talked about as something he really wanted to emphasize, especially in the choice of takes? A certain kind of emotional tenor. The movie is so multivalent in its offerings.

I mean, the film is about trust and jealousy and the interpretation of a piece of information that gets misinterpreted when she tells the story of the naval officer. So is it a film about trust, betrayal, sense of betrayal? It’s so many things. I think… Stanley never went that deeply into his own interpretation. I mean, one of the things I’ve always loved—Stanley has always been one of my favorite directors—is that he zeroes in on the human condition. It doesn’t matter which film you take, whether it’s Strangelove or Barry Lyndon or Clockwork: they’re all about different types of human condition. And Eyes Wide Shut was no different. I think it’s a much more personal issue, or much more an issue we’re familiar with, because it happens in everyday life in all relationships. And I think Stanley was fascinated by this.

I think that’s what fascinated him about Traumnovelle—you know, the book is based on this—and that’s only a short story. And so he would talk about it, but not so much intently on the psychological or theoretical side of it. It’s just, you know: does this feel real? I think more his approach was: do you accept this as being genuine? I think that’s one of the appeals of the film—it really scratches under the surface of the nature of the story—and I’ve always said that the thing I found most fascinating was to go and watch the film in a full theater and see how uncomfortable it makes men. Because it does. You see them rustling in their seats and getting sort of nervous at certain points in the film where men are being men.

No comment.

[Laughs] It’s one of the things I love about the film. I think that’s why, you say, you go to it and it seems to bring out something new every time you watch it—because it delves into areas where it’s very difficult to go to on film. I think his biggest concern with the film, the thing that worried him most, was what problems we were going to have with the nudity and the sex. And he thought there was too much sex in it; I told him I thought there’s not enough.

Really?

Well, because I think the trouble was: people were going to the film expecting to see Tom and Nicole in some kind of situation which never materializes in the film, and so they felt a little bit let down by that. Although Nicole gave everything she could. [Laughs]

Every time, I think that if I just sit at a different angle and look around the corner a little bit, I’ll discover the hidden meaning—the truth of the cult or certain intentions or… I could just keep going on and on. But you know what I mean.

Yeah.

I’m almost hesitant to even bring this up because it’s so stupid, but I don’t know if you’re aware that there’s this long-persisting rumor—“rumor” is being generous—that about 25 minutes were cut from the film that involve, like, Nicole Kidman reading from a book about the Illuminati, and that this was cut after Stanley Kubrick was murdered for exposing the Illuminati.

[Laughs]

It feels undignified to even ask you to clarify that it’s not true.

Well, it’s completely untrue.

Okay. Unless you’re part of the cult, but I don’t know.

I can tell you that nothing in the film that happened—and this includes after his death—involved anything that Stanley wasn’t aware of, or wasn’t aware that was going to happen. The difficulty that happened with Stanley’s sudden demise—and this was, remember, three days after I showed the film in New York: shown it to Terry Semel and Bob Daly at Warners and then, same night, showed it to Tom and Nicole—when I got back to London, Stanley was jubilant with the reaction. And we had a long, long-ish conversation, and the only thing that had to be done was mundane editing stuff. We had establishing shots to put in the film—you know, exterior buildings—and that was it.

There was nothing missing. That cut is Stanley’s cut the day he died. And nothing was over-edited. There was no Illuminati. [Laughs] I mean, I don’t know where these things came from, these ideas or concepts—because they’ve always built up around Stanley. It’s just the fact.

Previous Blu-ray edition [left] and new Criterion Collection restoration [right]

He was such a genius of film form, which only a select few people truly understand—and almost nobody understood like him—that some need to gravitate towards something that’s more spectral and conspiratorial because that’s something that they think they understand. I don’t need to psychoanalyze these people too much, but I think that’s what it is: they want him to be this envoy of a secret meaning. I mean, there’s this idiotic story that Roger Avary tells about how Kubrick got into some big argument over the editing, then was killed a few days later. I find it so irritating because Eyes Wide Shut is one of the smartest films ever made—Stanley Kubrick gave us this gift, and now people have to be like, “No, but it’s actually about something else.” It scares people, in a way.

Well, yeah, I mean, I can say Stanley and I had our arguments or disagreements, but it never led to me being fired, so it can’t have been that serious. [Laughs]

That’s a good point.

I think people, because of the circumstances that the film came out in… and you can imagine. I mean, like I said: I got back from New York on the Thursday; on the Friday we had this meeting; and on the Saturday night he died. You can imagine how I felt when I got a phone call about Stanley on Sunday morning.

Yes, of course.

And our duty, or my duty, was quite clear: you do exactly what we’ve been told to do. I’ve always been loyal to Stanley. I’ve been loyal to his privacy. And I’ve always respected him because he was loyal to me, and I own that loyalty. The only difficulty we really had with the film after him—because there was no plan B—was dealing with the MPAA. We were just a pain in the backside because they can’t cope with a bit of pubic hair. [Laughs]

And Kubrick loved pubic hair, too! It’s in so many of his films.

Well, it’s natural.

Yeah, that’s right. Human condition.

The Japanese waived their rules on pubic hair to the film rating.

I didn’t know that.

I took the film to Japan for the censor screening, and normally they would have insisted on blurring it all out. But they said, “You know, Kubrick is like Kurosawa—we can’t touch his film.” The MPAA didn’t have the same attitude. [Laughs]

Previous Blu-ray edition [left] and new Criterion Collection restoration [right]

There’s the enduring question of whether Eyes Wide Shut is a finished film. You lean towards: yes, it is a finished film, even with certain things that have to be put in. But I wonder what your exact perspective on it is with regards to things like color-grading and sound-mixing, which you had done a temporary version of.

The whole problem with those is—like I say—that’s a subjective part of the process. Regarding the color-grading with the DVDs in particular, my own personal feeling is: there was an error of judgment. Larry wasn’t available when we needed him, which I think was detrimental because he had stood next to Stanley while they lit the film. And with this process of force developing all the negative rather than just selective scenes, everything was forced to develop. It meant miscalculations were made when the grading was done—not so much in the film version, because the film was easier to deal with, but in the DVDs, especially the first DVD release. I was not party to that. That was not considered my department; that was Leon’s department. But I feel that this new grade of the DVDs is much closer to what it should have been originally.

I imagine so.

Stanley always graded the film himself. I remember it well on Full Metal Jacket. I may have been a sound editor, but I was at the house and, you know, he went through the same process: they would do test clippings and stuff with the lab, and he would analyze them and have slides and stuff, and he really thought about every aspect of it. But of course, on Eyes, not having Stanley was far more critical because we’ve gone through this process of force developing all the negative material, which has a bigger effect on the daytime stuff than the nighttime stuff. It was force developed, really, for the nighttime stuff. But the daytime stuff becomes too bright or becomes brighter by default, because it’s already properly lit rather than under-lit, which is the part of the process of force developing: you’re under-lighting, effectively. But in daytime, when you’ve got natural light, you don’t suffer from that problem.

It always concerned me, because I always felt the DVD was never right. And I think Criterion, it’s great that they’re doing this, and Warners agreed to it, and Warners did a new scan of the negative, apparently. So it’s a clean sweep, and I had lunch with Larry after he finished the grade to talk about it. It’s just unfortunate. And the sound: there’s only one person who can be held responsible for that, and you’re looking at him [Laughs] because obviously I’d been sound editor on Full Metal. And when I did this, I knew Stanley… we picked a sound editor on the film who had worked with me on Full Metal, but Stanley always, I knew, I was the one who was going to get the bollocking. [Laughs] Not anyone else. So taking care of the sound was not an issue.

You know how he found that piece of Ligeti music, the piano? He found that the week before I went to New York. And we did a full temp mix of the film before I went. But I had never seen him so excited as when he came down the stairs, waving a CD, saying, “I found it, Nigel! I found it.” The first time he put it up against the film, it was just magical.

No, it is. I mean, every time it pulverizes me.

You know what it is? It’s actually a piano exercise by Ligeti.

And now your work in bringing it out can be heard better than ever. I really do mean this when I say it was an honor to have your time after you’ve done so much to create one of the greatest films ever made.

Thank you.

Yeah, no, I mean—I don’t say that to everybody, I promise. I hope you can watch this Criterion disc and take a bit more pride in your work, because I think they did it right. Thanks for talking.

I hope it’s helpful to you.

Eyes Wide Shut will be released on the Criterion Collection on Tuesday, November 25.