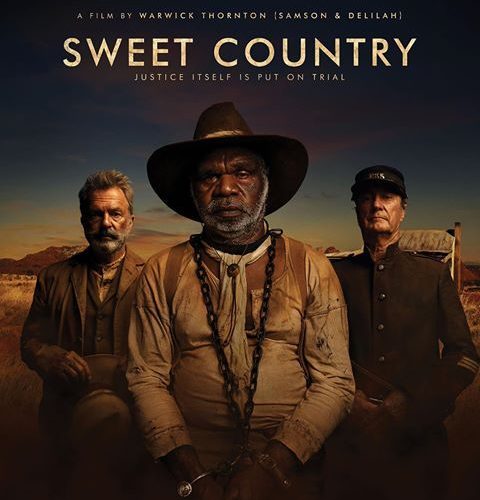

At the very end of Sweet Country, director Warwick Thornton’s stunning, somber outback western, an emotionally devastated cattle rancher played by the great Sam Neill offers two questions to the clouds: “What chance have we got? What chance has this country got?” It’s the sorrowful capper to a powerfully upsetting film. And it’s entirely fitting. Sweet Country is many things — a stark western, a gripping chase story, a tale of slavery and self-defense, and a searing drama in which the stakes are horrifically high.

Set in Australia’s Northern Territory in the late 1920s, the film is anchored by Hamilton Morris, a non-professional actor who gives a simple, tremendously engaging performance. Morris plays Sam Kelly, an aboriginal stockman who works for Neill’s Fred Smith. The latter is a vocal Christian and one of the few onscreen whites who does not openly discriminate. Thus he is the opposite of Harry March (Ewen Leslie). A cruel war veteran and drunk, March is in need of helping hands. Smith makes the mistake of sending Sam and his wife, Lizzie (Natassia Gorey-Furber), to work for March, and the effects for all concerned are seismic. (A nightmarish scene of March assaulting Lizzie in a pitch-dark room is particularly effective.)

Once work is done, Sam is forced to kill March in self-defense. Doing so likely saves his life, Lizzie’s, and that of a young aboriginal boy named Philomac (Tremayne Doolan). But Sam has a keen understanding of his place in Australian society. He and Lizzie are voiceless, and their lives expendable. Hot on their trail is Sergeant Fletcher (big-screen vet Bryan Brown), a merciless authority figure intent on finding the killer. He is the leader of a motley posse that also includes Smith — a scene in which Neill poorly sings a Christian song around the campfire provides the only notable laughs — and an Aboriginal tracker named Archie. The latter is one of Sweet Country’s most interesting figures. Archie knows his role, yet also offers one of the film’s standout lines: “It’s not my country. My country’s far away.”

Indigenous Australians, like Sam and Archie, are referred to here as “blackfellas,” and they are treated with little more than contempt. This makes the makeshift trial of Sam particularly fascinating. And the presence of aboriginal voices makes Sweet Country a more profound and memorable western than, say, John Hillcoat’s The Proposition. Some of Country’s most sadly insightful scenes feature Sam and Lizzie alone around the campfire, remarking on the “troubles” that are coming.

What Sweet Country lacks in surprises is more than compensated for with emotional power and haunting images. The outback has rarely looked so harsh and unforgiving. Australian director Warwick Thornton, whose debut feature Samson and Delilah earned the Caméra d’Or at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival, achieves something rather noteworthy here. He has created a film set in eerie, wide-open spaces that also feels utterly claustrophobic. There is nowhere for Sam and Lizzie to hide, and no place that feels the least bit welcoming.

Never is this truer than during the film’s final moments. And while the conclusion feels a bit predictable, it is indeed potent. As Neill cries out in sadness, it is hard not to feel overcome by Sweet Country’s grim strength. Thornton establishes himself as a director to watch, and with fine performances from Neill, Brown, Gorey-Furber, and, especially, Hamilton Morris, also reveals an ability to make an epic tale feel deeply personal.

Sweet Country screened at the Sundance Film Festival and will be released on April 6.