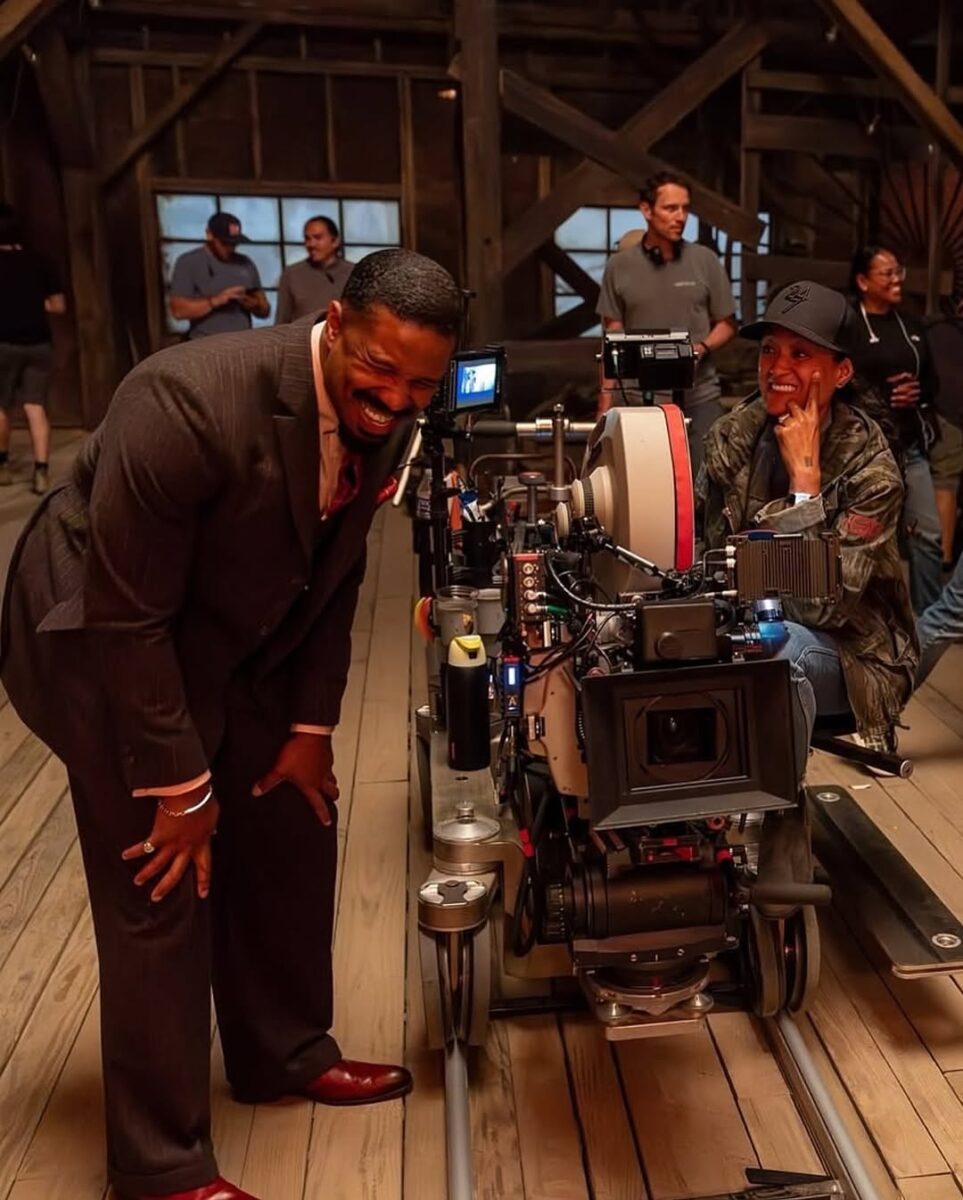

Exceeding all expectations, Sinners became a critical and box-office hit when it was released this past spring. Written and directed by Ryan Coogler, the film stars Michael B. Jordan as twins Smoke and Stack, who set up a juke joint in the deep south in 1932. By challenging racial norms of the time, they unwittingly unleash deadly forces.

For Sinners, Coogler collaborated with cinematographer Autumn Durald Arkapaw, continuing a relationship that began with Black Panther: Wakanda Forever. They decided to shoot on film, employing two formats: IMAX 15-perf and Ultra Panavision 70. Arkapaw became the first woman to shoot a large-format IMAX feature film. Arkapaw’s previous feature, The Last Showgirl, was her third with director Gia Coppola. She has also shot documentaries, television series like Loki, and extensive music videos.

Ahead of an IMAX 70mm re-release at select theaters beginning Dececember 12, I spoke with Arkapaw at this year’s EnergaCAMERIMAGE in Toruń, Poland, where Sinners screened in the Main Competition. Generous and outgoing, Arkapaw participated in panels and Q&As at the festival, spending time with both fans and colleagues.

The Film Stage: First, let’s talk about the formats for Sinners. The film switches from 1.43:1 IMAX to 2.76:1 widescreen.

Autumn Durald Arkapaw: It was a pretty bold choice from Ryan. I mean, it’s never been done before. I think we’re the eleventh film to shoot on Ultra Panavision 70, so it’s not a format that gets used often. It’s also difficult to preserve your aspect ratio in theaters. Some 2.76 films shot digitally in the past often had the sides chopped off. When Tarantino did the roadshow for The Hateful Eight, he had projection specifications for theaters.

We love IMAX, and we felt that the different formats could say different things. We put together a test reel and watched it at IMAX headquarters. It felt right. It felt beautiful. It didn’t feel like the wrong choice.

Did you have specific plans for jumping from one format to another?

It’s not about the jump; it’s about the format. When we’re planning out our shooting schedule, looking at full scenes, that’s when we make decisions whether we’ll be on IMAX or 2.76.

What are you aiming for by switching formats?

It’s something they played with in the edit. As a storyteller, Ryan’s working with [editor] Michael [Shawver], figuring out when to be more aggressive or not, you know? So there’s a montage at the end where Ryan does do a little bit of more back and forth. Ryan’s choosing these shots because they tell the story emotionally. He cannot make a 2.76 shot be an IMAX shot, so ultimately it has to jump because that’s how it was filmed. I feel it’s more about the emotional quality of the image than looking at the ratio.

Moviegoers who see it in 2.76, they don’t feel this question you’re asking me, right? Because there are no jumps. The only person who’s going to feel this montage jumping back and forth is someone who sees it in IMAX.

The first time you see Remmick [Jack O’Connell], that’s an IMAX shot. There’s a lot of foreground to the frame; the camera moves are disorienting. As a viewer, you’re suddenly in a different world. I wasn’t sure what I was supposed to be looking at.

Well, you’re supposed to be looking at everything. It’s a big frame. It feels like a medium-format photograph, something we’re familiar with. It’s boxier; it has very shallow depth of field.

In an IMAX theater, you have a hundred-foot screen. Your eye has to be intelligent enough to look around. There’s so much to see, so much depth to the image, that when you look at the foreground—where the focus is—you also see the house in the background. The house isn’t in-focus, but you’re aware of it. Because the resolution is so large, you can see both layers.

Your eye does have to travel; it has to move around to see everything. And your eye does move differently for a 2.76 image. Part of the IMAX experience is that there is so much to look at and absorb. It causes you to have a relationship with the format, to choose what you want to look at. Which is part of the fun.

Some IMAX DPs don’t want to move the camera that much.

We love to move it around. That was important to Ryan. He got advice from Christopher Nolan to treat the camera like a Super 8 camera. Move it around as you normally would and tell your story; don’t feel restricted because it’s bigger or louder. Ryan and I followed that advice. We put it on Steadicam a lot. We put it on cranes a lot. To be able to do that, you have to have amazing focus-pullers. I’m very proud of my camera assistants for their impeccable work.

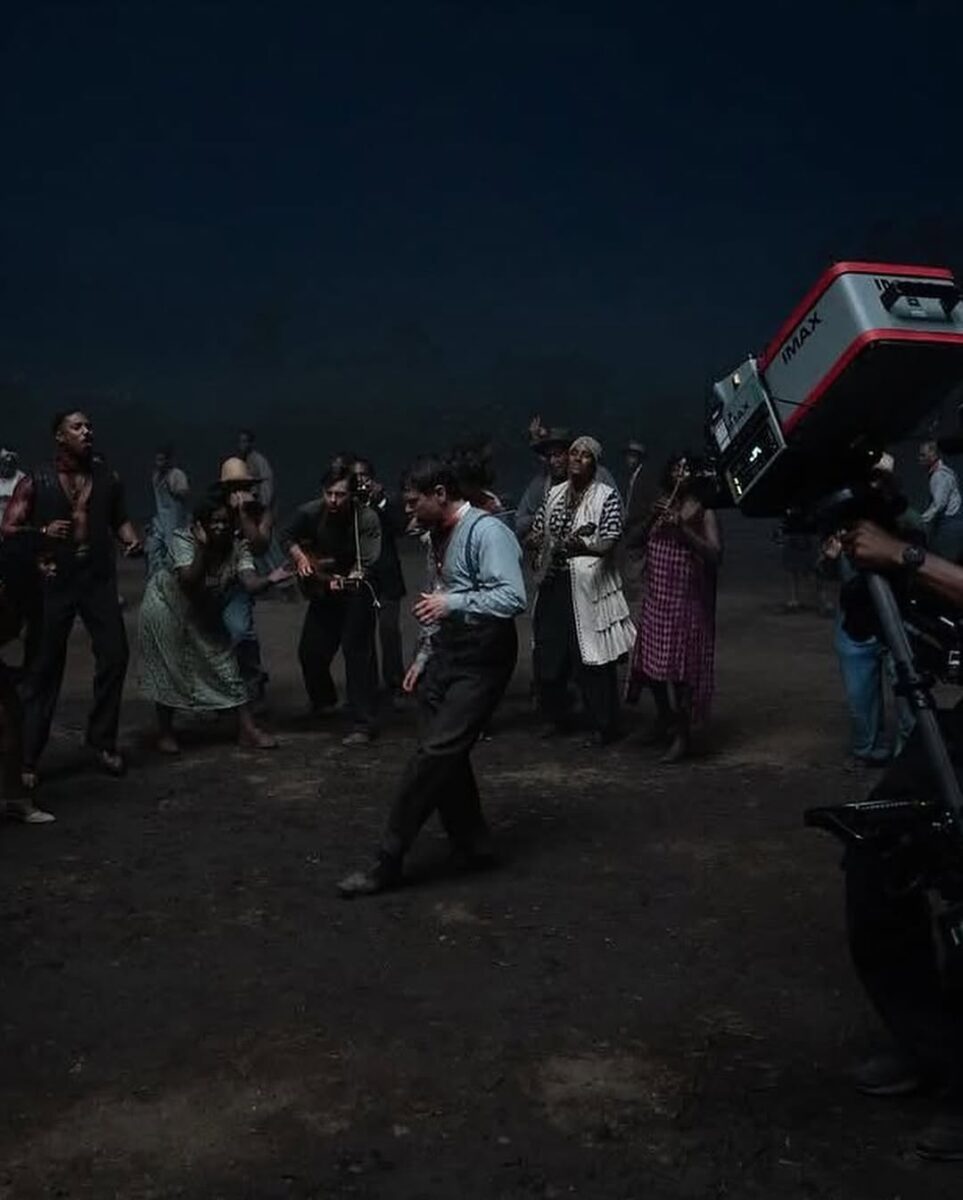

Did you know what music Ryan was going to add to scenes? Did that affect how you shot?

I didn’t know all of the music for every scene, but I did know the tracks to our musical sequences. For those, we shot with the track playing. It was great to have Ludwig [Göransson] on set. When Remmick is doing his jig outside at night or Sammie [Miles Caton] is performing “I Lied to You,” the camera movements are planned with the music in mind.

The music gives you tempo and pacing, especially during that remarkable one-shot tour of world music in the juke joint.

That’s the shot that I get asked about the most, something people really responded to. No one’s ever seen anything like that before, especially shot on IMAX. On the page, it’s a beautifully written and complex scene. Once we get on the ground with Ryan during prep, once we figure out what it means to him and how he wants to execute, then it’s a lot of logistical meetings with all the departments. We shot it with Steadicam, and in order for the operator to hold it, you can only run 75 seconds before you have to switch the magazine. Since the song is over three minutes, we have to figure out where we will transition from one shot to another, and then the second half of the shot takes place in a different location, shot on a different day.

It’s a lot of very smart minds coming together to figure out how to execute. Still, at the core, you always want to be telling the right story. You don’t want to draw the audience away from what the story’s really about. I think why that shot is so successful is because all departments really worked together beautifully to pull it off. I think Ryan was very happy with it. It’s very emotional, it’s a departure from what you’re normally seeing, and it introduces these new characters. It also provides so much history in one fluid scene. With the sound mix, you really feel it in the theater. Especially in IMAX theaters, the sound reverberates and fills the room.

Can you talk about how you compose shots?

I’m operating the camera, so Ryan and I are physically next to each other when we’re shooting a take. He loves to be right next to the camera. We do a rehearsal; we like to vibe off the space and how the actors are moving in it. When the actors come back from hair and makeup, Ryan and I have talked about what we want out of the scene, and what shots we need to tell the story. I’ll set up the first shot and show it to Ryan, and then we have a discussion about it.

I’ve known Ryan for a while now––Wakanda Forever took a year to shoot, a very, very complex movie where sometimes we’re shooting two cameras, sometimes we’re shooting six cameras. You really get to know somebody and what they want out of camera when you do a picture like that. I have a clear sense of how he wants to tell the story emotionally, and there’s one camera position that captures that feeling best. It’s my job to find that and then offer that up. We storyboard everything. That gives us a structure, but it doesn’t mean we can’t change on the day we’re shooting.

So you don’t feel locked into storyboard or pre-vis? Is there any wiggle room?

Wiggle, yes. Pre-vis is a tool to figure out logistics for some complex shots. Big action sequences need to be planned as far as how many shots they will need, where the transitions will be, how to work out the VFX elements, what has to be timed to music.

Pre-vis is a great tool that allows you to prep for all of that, but also know exactly where you want gear to land. What’s great about Ryan is that we can prep all day long, but when we’re on set, we’re always reacting to what’s in front of us. If there’s an emotional response or the light is hitting a certain way or Michael wants to go in a different direction—we lean into the emotion that’s already there. That’s what produces the most compelling image.

Your shots seem so precise, so beautifully composed, I can’t believe you’re suddenly grabbing something.

No one’s “grabbing” anything, but you have to be open to change if the previous plan doesn’t feel right. For something like the oner, it has to have seams in it because the camera can’t run for the entire length of the song. That requires you to work out the logistics—solve the problems—based on pre-vis. With a simple dialogue scene, you can plan to shoot a wide shot, a two-shot, and overs. But if the actor all of a sudden decides not to sit in the chair, or you see that sitting in the chair is not appropriate for the scene, you want to be able to be reactive, to change it, to work with what’s in front of you and what feels right in the space.

When I’m watching a film, I can feel when the camera becomes one with the actor. When they’re in sync, it’s the most beautiful thing. So if you’re ever on set and something feels off—maybe you boarded the shot one way, but once you’re in the space you realize the camera shouldn’t be there—then it’s your job as a DP to move it.

That only works if you’ve prelit the set. You can’t suddenly shift all these lights.

A good DP knows how to make decisions quickly. I like to light the space because I want Ryan to be able to move the camera freely and not have to constantly tell him, “Um, I didn’t light over there, so I need more time.” So yeah: I tend to light the space. Also, I don’t want a lot of stuff on the floor that will prevent actors from moving around. It’s like poetry in a way. Sometimes it has to ebb and flow in a nice way so you don’t restrict the actors or the director. You want them to be able to find it, when it needs to be found.

The production designer and I are also very good friends. I love working with Hannah [Beachler]. Together we can make sure we have sets with motivated lights, where we can put bulbs where we know scenes will need them. So thinking ahead with the designer is very important.

We haven’t talked about “twinning” effects with Michael B. Jordan playing two roles.

We used every trick in the book, from programmable camera heads to a TechnoDolly to body doubles. The credit really belongs to Michael for playing two distinct characters so effortlessly and beautifully.

Do you worry about framing for Blu-ray when you’re shooting?

We do our Blu-ray pass in post after we do our theatrical formats. For the theatrical, you also QC it in 2.76, because that’s how the majority of the audience will see it. The 2.76 is the grade that you’re kind of hinging all the other deliverables on. Then you do your IMAX framing pass. I’m looking at how to adjust the IMAX frame for 2.76. You have so much top and bottom you can shift to make sure you have perfect framing. Because I like to center punch my compositions, the IMAX pass isn’t that difficult. When you center punch your images, everything has a nice center line. Then the Blu-ray pass is its own thing, because Blu-ray has a 1.78 container. So you’re making sure that the 1.43 image sits well inside the 1.78 container.

You don’t want to bog yourself down with all of the logistics of deliverables. You don’t want to make a movie about deliverables. As an operator, you want to make sure you’re doing a good job storytelling. You stay aware of all the aspect ratios, but they live in the back of your mind. What matters most is creating an emotional image.

Sinners returns to select IMAX 70mm theaters on December 12 for one week only, and is now on disc, digital, and HBO Max.