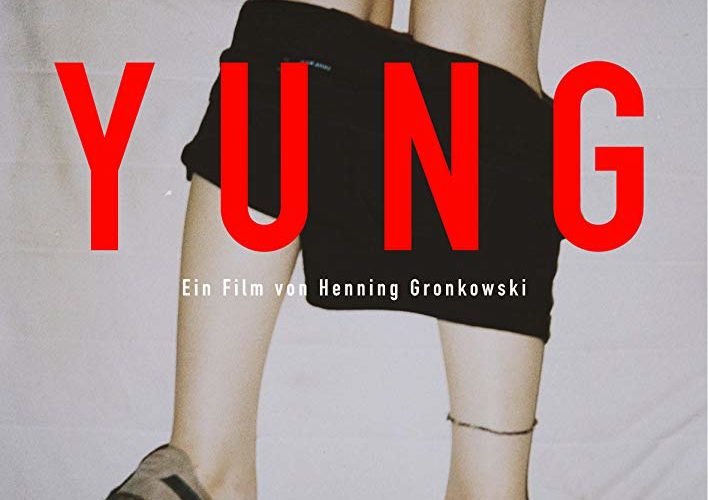

Bodies twirl to maddening EDM tunes and wobble home at the break of dawn; nostrils are pierced, snort coke and puff smoke; mouths chew, bite, and meet in voracious kisses; legs squat, twitch, and thrust against naked bodies. Every frame of Henning Gronkowski’s electrifying feature debut Yung exudes a raw physicality, a primal and bodily beauty that springs out of an orgiastic tour de force into the drug-, booze- and sex-propelled lives of four Berlin-stranded teenage girls. Dancing between fiction and documentary until the distinction becomes irrelevant, this manic dream of a film conjures up an uncompromising ethnography at once hallucinatory as a drug-fueled trip, and hyperreal as its bodily aftereffects.

Unfurling like a plotless Bildungsroman caught halfway between Larry Clark’s Kids and Michal Marczak’s All These Sleepless Nights, Yung zeroes in on a quartet of 16 to 18-year-old best friends united by a sense of drift and different forms of self-destructive behavior. Janaina (Janaina Liesenfeld) works as a webcam girl and escort; Joy (Joy Grant) cuts and sells her own drugs to mates and ravers; Abbie (Abbie Dutton) daydreams of moving to LA in between a party and another; and Emmy (Emily Lau) is so addicted to drugs by the time she admits to “have done enough stupid stuff for three lifetimes,” the confession sounds like an understatement.

Very little is said about the rationale behind their troubled life choices, partly because–save for the occasional sixty-somethings who pick up Janaina aboard SUVs, pay to have sex with her, and dispense the sort of mindless small talk you’d expect from an estranged father (“Did you have a good weekend?” “What kind of music do you like?”)–Yung’s is a virtually adult-free world. Parents are squeezed off frame, and only pop up in a coda that–95 minutes of raving and drug intake later–feels disturbingly cozy.

To be sure, Janaina–whom Gronkowski lingers on with greater intensity than any of the other three–does articulate her sex work as a means to gain independence from her mother, but the explanation hardly accounts for the near pathological substance abuse the quartet happily indulges in, gulping liquid ecstasy with the strenuous commitment Hong Sang-soo’s characters put into soju. “Most kids don’t want to admit they’re addicts,” warns a male friend of the four, and the statement rings achingly true: Gronkowski’s lead characters may well be aware that what they are doing “is not good”–as one of them euphemistically puts it–but there is an insouciant nonchalance in the way they readily justify the extremes as “just part of life,” and a sad naïveté in the shared illusion that, like any other temporary stage in one’s adolescence, this too shall naturally run its course.

Even so, Gronkowski steers clear from parceling out simplistic judgements. That the four girls’ addictions are lethal and drugs are bad is Yung’s starting premise, not a lesson we are spoon-fed ad nauseam throughout it. What matters here is not just how much and what is consumed onscreen, but how unexpectedly endearing and compassionate Yung ends up treating its four heroines, and how intelligently Gronkowski avoids to either patronize or glamorize their aimless drifting.

To be sure, part of the credit goes to the film’s autobiographical vibe. In a surprisingly emotional Q&A after Yung’s international premiere at the Tallinn Black Night’s Film Festival, where the film competed in the First Features’ lineup, Gronkowski referred to the project as a cathartic experience–a means to come clean after years lived dangerously close to the four characters’ own deranged existence. A protégé of German Indie icon Klaus Lemke–starring in his Finale (2007), Berlin für Helden (2012), and Unterwäschelügen (2016)–the 30-year-old actor-turned-director prepared for the film by revisiting old spots of the Berlin club scene and digging up from his and the cast’s own antics. If the portrait ends up feeling so authentic, that’s because it’s been patched together someone who wends his way through clubs and concerts with the confidence of an aficionado.

But the heartfelt sense of empathy Yung shares for its four girls also owes to the way Gronkowski pens them as multi-dimensional characters, and gives them ample time to just be and speak for themselves. I mentioned All These Sleepless Nights as a reference point for Yung’s themes and visuals–if anything, the loose meandering and ongoing partying do make for a terrific double feature. But while Marczak’s film managed to create a time-space continuum of Malickian beauty in which the drugs and EDM-peppered peregrinations of his cast merged into a boundless, uninterrupted odyssey, Gronkowski interpolates all the partying and drifting with several talking-head shots, during which the girls sit down and open up to the camera.

It’s a series of confessionals wherein the four take turns to share their musings about life (from their love for “giant K-hole” Berlin to their history of substance abuse) with an effortlessness that graces the monologues with an improvised, unscripted vibe. And although the unadorned setting and the chats’ content may make the scenes look like a protracted AA session, there is nothing explicitly extractive or oppressive about them. Far from placing the girls in a glass box for them to be scrutinized and scolded, the talking heads serve as interludes for the quartet to share their fears and expectations for the future, as much as to elaborate on their commitment to the hedonistic life they’ve chosen to follow. There is hardly ever a hint of an apology in their confessions, and even when the topic turns to the dangers their lifestyle carries, the four readily shrug the fears away, hiding behind vague promises and future resolutions.

After all, they do live up to the full meaning of “yung” as that preternaturally cool mode of being in the world: Gronkowski respects them for who they are, and invites us to do the same. They may be imperfect and severely troubled, but there is something disarmingly charming in the way they are able to express themselves freely and unapologetically–reclaiming a right to be young, messy, and self-destructive.

Nothing feels more oppressive than the realization that there are no limits to what you can do with your life, but what makes Yung so painfully nostalgic is that it follows four teenage girls as they discover the opposite–that there are in fact limits to how things will play out. The people we love may not like us back; our bodies can only take so much ecstasy before pleating to the ground; and friends who need our help will do everything they can to escape it. Drugs are a prêt-à-porter panacea to forget about all that for a few hours; life–in its substances-propelled variations–an emotional rollercoaster stashed with moments of unrealistic intensity and short-lived thrills.

And Yung understands it all too well. This is a film of snapshots instead of large canvasses, of unassembled memories as opposed to three-acts plots, of episodes rather than long-form stories. EDM music bleeds it all together–courtesy of the beats of DJs as varied as MC NZI, DJ Hell, Abblou, Vegas, Fango, Malakoff Kowalski, Benjamin Lysaght, and Cameron Avery–so omnipresent to turn into a hum perpetually reverberating across rooms. Director of photography Adam Ginsberg adjusts to the cacophony with a free-floating camerawork that works just as well for the frenzied party scenes as for the sobering walks home. Tenderness may be hard to come by in the quartet’s fast-paced, frenzied lives–but it is here, in the few moments of intimacy the friends share along the way, that Gronkowski and his terrific cast nail some scenes of heartwarming stupor.

For all its raving, Yung remains an ode to four friends. It feels moving and compelling precisely because it manages to celebrate them in all their complexities, refusing to either glorify or condemn their excesses, and taking them instead for what they are: the escape mechanisms of a few teenagers who, as one of them so eloquently observes, “have grown up too fast.”

Yung screened at the Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival.