The Words, written and directed by Lee Sternthal and Brian Klugman, is an unabashed piece of romantic cinema. It’s central romance? The written word; the idea that sometimes, for better and worse, art overtakes everything else.

Bradley Cooper stars as Rory Jensen, a recent college graduate determined to make his way and make his mark as a writer. Unfortunately, Rory doesn’t have any source of income, still asking his dad (J.K. Simmons) for money.

His new wife (Zoe Saldana) completely supports the dream. That’s about all we learn of this underwritten character. Once again, another Zoe Saldana performance wasted completely on her looks, which, though impressive, only breach the surface of the girl’s abilities. On their honeymoon in Paris, Rory comes across an old leather suitcase at an antiques shop, which Dora insists she buy for him.

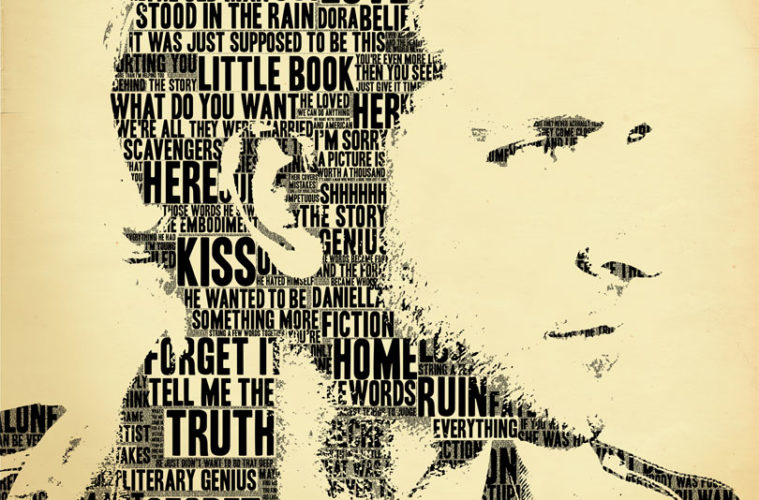

Inside the suitcase is an yellow-tinted handwritten manuscript. A brilliant novel in fact, which Rory can’t resist to copy. Before he can blink, he’s the literary darling of the moment, the book he’s found published in his name. The literary ability/success he’s always aspired to be has come true for him, thanks to something he didn’t write.

What follows isn’t as “Tell Tale Heart” as it would appear. While guilt does play a part into the narrative a bit, it’s one piece of a much bigger puzzle. A puzzle fueled by the idea of the person telling the story and who the person had to become to write such a story. Dennis Quaid opens the film as an accomplished novelist, reading from a new book entitled The Words, about a book stolen by a young man named Rory Jensen, and the Old Man (Jeremy Irons) who wrote it.

Irons, who seems to only get better with age, revives the film just as it’s getting a little stuffy and melodramatic. His Old Man is a bitter, honest soul eager to tell his story to anyone, even the man who stole it from him. As Irons begins to recall the past which inspired the book, we travel further back into both time and story. A narrator narrating the words of a narrator.

The filmmakers don’t do quite enough with this post-modern device, using the story-within-a-story-within-a-story through-line simply as a storytelling device of their own, something that’s both ironic and fascinating in many respects. Luckily, the high drama and high dramatic acting on display here (most distractingly from Quaid, who feels like he doesn’t belong) is aided by a beautiful score from Marcelo Zarvos. It’s soon revealed, minutes into Irons’ introduction, the largest piece of this film’s puzzle is that of love lost.

As Irons transports Rory and the audience to 1940s Paris, after the war, Zarvos’ strings and soft piano the tone Klugman and Sternhal are trying to achieve, that of the star-crossed tragedy of an artist, his work and his muse. As Irons so eloquently puts it at the end of his tale: “I cared about the words more than the woman who had inspired me to write them.” The regret seeps through his stained skin and grizzled beard. Cooper, while strong enough and the technical lead here, nearly disappears off the screen during Irons’ onslaught of performance.

And for all of the film’s flaws – most of which revolve around the script’s reliance on constant narration and question-popping cyphers with no foreseeable motivation (Olivia Wilde) introduced solely to move the plot forward – it wears its heart on its sleeve. This is the kind of movie about artists that artists hate to love, but love anyway. I’ll bring the tissues.