Though she was popular nearly a century ago, Florence Foster Jenkins feels particularly relevant to modern art’s ongoing dialogue with awfulness as a version of the sublime. In another world, Xavier Giannoli’s prickly tragicomedy Marguerite could easily be an exercise in self-loathing in the same fashion as Rick Alverson’s films, but instead it’s a film whose virtues lies in a fierce neutrality towards its own subject. Even the characters who appear to be the most transparently kind or evil contain multitudes, and the film becomes a constant examination of its own tone.

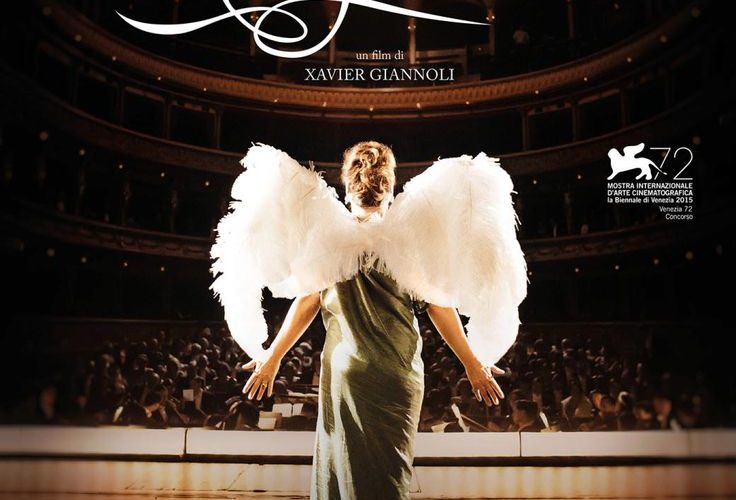

As such, Marguerite is frantic and compellingly unpredictable, even as it heads into comfortable territory. Loosely based on the life of Jenkins, a ’20s-era socialite and Opera singer renowned for her supernaturally abhorrent voice (here’s a recording of her murdering every poor note of Mozart’s Der Hölle Rache), Marguerite follows Marguerite Dumont (Catherine Frot), a European socialite whose considerable wealth enables her to sing behind closed doors at charity events even as spectators are more hostages than willing listeners.

The real-life Jenkins became a global oddity, persistent in the belief that she was as talented as the contemporaries of her time. Marguerite doesn’t let its protagonist reach these heights of ignorance, instead telling a story that places Marguerite into a late dada movement as a form of political resonance. She’s a fool in the vein of Sunset Blvd.’s Gloria Swanson — willing to spare no expense at her illusory chance to be a star, even as nobody has the heart to tell her the truth about her singing. But Marguerite is also not afraid to give its lead a begrudging respect for her overwhelming efforts.

Played by veteran French actor Frot — who, for her tremendous performance, received one of the film’s four César awards — Marguerite is positively luminous in her effusive reaction to the art of Opera and her unrelenting enthusiasm, but Frot walks a far more perilous tightrope in bringing across a combination of obliviousness and deep realizations about her failings as a singer.

Any number of points in the text could be used to prove Frot’s alternating awareness or ignorance, and that’s’ what makes Marguerite such a hypnotizing figure: she’s convinced herself so thoroughly of her own passions that the truth would literally break her entire sense of existence. Surrounded by a phalanx of (somewhat) well-meaning yes men, the people around Marguerite coordinate their actions to support the ruse, even going so far as to hide damning reviews in local papers and blackmailing singing teachers into trying to improve her impossible craft.

Her small-scale ambitions soon expand with the intervention of Lucien Beaumont, a reporter, and his radical artist friend, who sneak into one of her events and write a glowing review of her voice, which charitably could be described as like a dog whistle meeting a dying monkey’s last shriek. Flattered by the review, Marguerite teams up with the two men as they hatch a more grandiose scheme to push Marguerite onto larger stages for their amusement.

The story is mostly told through Marguerite’s perspective, though the story will sometimes switch to Beaumont, the Joe Gillis-type who first reviewed Marguerite’s show. Played by Sylvain Dieuaide, Lucien refuses to be pinned down, stoking the fires further of whether the film’s laughing with or at Marguerite. In between, he’s hashing-out his feelings for Hazel Klein (Christa Théret from LOL), a struggling Opera singer who actually deserves the larger attention, but is continually slighted by him in favor of spending time with Marguerite.

Meanwhile, Marguerite’s husband, Georges Dumont (André Marcon), is so ashamed of his wife that he’s sabotaging his own car’s engine in order to have an excuse not to endure his wife’s singing. Georges isn’t merely a farcical punchline about the lengths people around Marguerite go in perpetuating her delusions. Georges routinely walks out on his wife to sleep with a local gallery owner, but their conversations are pained exchanges about his wife — a person he loves but can’t like anymore. Delivered with a brusque sigh, his line delivery is slyly funny, but never fails to communicate the undercurrent of tragedy. All the while, she’s encouraged by a fiercely loyal butler, Madelbos (Denis Mpunga), who, in a second touch to Sunset Blvd., strongly resembles Erich von Stroheim’s character in more than just his broad haunches and the regal stiffness of his facial expressions.

Giannoli’s ease with sugary, poisonous dialogue and the cumulating orbit of characters can’t quite mask the crowded plotting, however. Fundamental characters slip in and out of the film with such frequency that the story could be knocked off-balance every time a new character returns from a long absence. In particular, the latter half of the story centers the characters into the most conventional narrative structure as Marguerite prepares a grandiose, eighteen-song show. That scenario lends itself to plenty of wry comedy as a hapless Opera has-been (a standout Michel Fau) deliberates over his life choices and unleashes his regrets on Marguerite. Still, while these moments are deeply entertaining, and serve as a parallel to Marguerite’s own crisis; this second half of the story feels particularly disengaged with all else.

But compared to fraudulent, pandering, recent films such as Eddie the Eagle, which want to give their main characters a participation prize even as their passions won’t respect them, Marguerite doesn’t automatically hold its main character as some diamond in the rough. Its feeling are more complicated — as if it wants to embrace the main character so tightly that she’s suffocated in the film’s grasp. As Madelbos says with the subtlest of sneers near the end of the film, “It’s not about doing something great, it’s about doing what one does with greatness and beauty.”

Marguerite opens in limited release on Friday, March 11th.