For way too long now, the concept of #girlpower in comedies has been dominated by white female narratives in which women of color are an afterthought, either playing an assortment of nondescript characters or sassy sidekicks who are always a call away from the white heroine, just waiting to help her solve her problems and win the man. For every How to Be Single, Bridget Jones sequel, He’s Just Not That Into You, and Bridesmaids there are approximately 0.05% (not a real statistic, but it feels like one doesn’t it?) women of color-led comedies out there starring women who aren’t J.Lo. Therefore, Malcolm D. Lee’s Girls Trip feels like the first of its kind: a raunchy, endlessly entertaining comedy written by and starring black women.

Even though it doesn’t seem like Girls Trip is up to much — it has a by-the-numbers plot and a lesson we see coming five minutes into the running time — it’s a reminder of the snail pace with which progress arrives in American culture when it comes to art about women. Seven years ago, male and female critics alike got their claws out to destroy Sex and the City 2, a film which they suggested celebrated excess, debauchery, immorality, and all the qualities they had admired the Golden Globe-winning The Hangover for. If the Sex film wasn’t inventing hot water, it was never meant to either. It was supposed to be a love song to fans of the HBO show who wanted to keep up with their Fab Four as they mourned the void the show had left in popular culture.

Watching Girls Trip, I couldn’t help but have bittersweet, mixed feelings about Sex, which happens to be my favorite TV show of all-time, but which evidently has not aged well in terms of racial dynamics. The four protagonists were all white, and except for the rare exception in which the characters would sleep with a random black man, or a Brazilian woman in the case of Kim Cattrall’s Samantha, people of color were absent. We can still celebrate the show for the way it tackled female sexual empowerment and celebrated the importance of friendship, but take into account how little regard it had for anything not related to white feminism.

That buildup is only to say that Girls Trip is, in a way, the Sex and the City movie we were promised when the show was over. It’s a celebration of strong women, who have the reins of their professional lives, feel comfortable in their own skin, and are so at ease with their sexuality that they can say that “daily penetration is medicinal” without as much as blinking. In a way, screenwriters Kenya Barris and Tracy Oliver have made a film that reclaims the space the landmark HBO show denied black women.

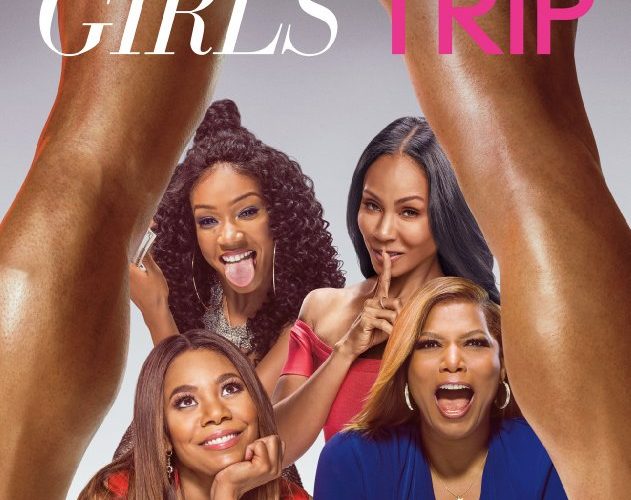

The four leads in the film seem like extensions of the archetypes from the show: we have the Carrie, Regina Hall’s Ryan, a successful writer living the dream life with her football player husband Stuart (Mike Colter); the Miranda, Queen Latifah’s Sasha, a no-nonsense businesswoman running a popular gossip blog; the Charlotte, Jada Pinkett Smith’s Lisa, a divorced mother of two who isn’t sure how to get back into the dating game; and the Samantha, Tiffany Haddish’s irreverent Dina, who wears her libido on her sleeve, but proves to be not only the most confident of the women but also the most loyal friend as well.

The plot, in which the four friends — known as the Flossy Posse — are reunited for the first time in years at the Essence Festival in New Orleans, follows all the conventions we’ve come to expect from trip movies. They accidentally end up in dingy accommodations, get a little too drunk which leads to hilarious situations, and also realize they need to do some severe healing in order to sustain the bond they share. Lee doesn’t seem to intrude in the work of his ensemble. He allows the actresses to give the film its flow and heart. Structurally the movie takes us from comedic situation to situation, with moments in between in which the four friends talk about life, love, work, and relationships that ache with longing and unbridled joy.

Perhaps what’s most telling about how the film riffs on Sex and the City is how they all wear a “Flossy Posse” gold necklaces, reminiscent of Carrie Bradshaw’s iconic piece of jewelry. Perhaps the film is suggesting these women too watched the show and wanted to be able to have what the white protagonists did. Even though race doesn’t specifically show up as an issue the film is trying to discuss, everything made in America is inherently tinged with racial politics. That the film gives its protagonists a space of respite in the form of a festival that celebrates “black girl magic” (at one point Ava DuVernay appears as herself discussing the concept) is both generous and also an important reminder of how the rest of American culture needs to catch up when it comes to cultural appropriation and the way black women are talked about and portrayed. The women in Girls Trip wear a necklace celebrating community, rather than individualism — even when they each have distinct, unique personalities — and considering the important role black women had in the 2016 election, Girls Trip is a timely reminder that when the Flossy Posse wants to celebrate and go on a vacation, we better be there to hand them a welcome cocktail, move out of their way and, if they’ll have us, join them on the dancefloor.

Girls Trip opens on Friday, July 21.