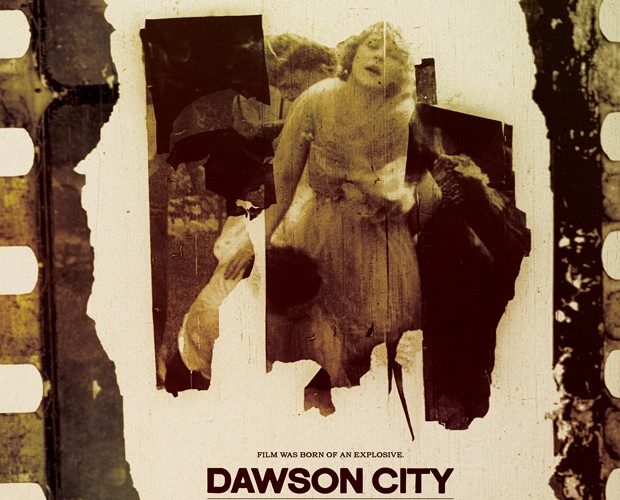

There is a scholarly theory that proposes films are always telling the story of their creation, singing an endless song about their own history. That seemed to have been literally the case in 1978 when Frank Barrett, a construction worker in Dawson City in the northern Yukon, discovered strips of nitrate film poking out of the earth in the site of a new recreation center — like stubborn blossoms trying to defeat the harshness of winter. Children had taken to lighting the visible strips on fire unaware that in the joy of the pyrotechnic display they were erasing history. Barrett’s unique discovery led to the unearthing of over 500 reels containing films made in the 1910s and 1920s, and considering that it is believed that 75% of all silent films were lost, this might have been the most important finding in the archaeology of film. Taking clips from these reels and solving the mystery of how they ended up buried in the Yukon, director Bill Morrison made Dawson City: Frozen Time which might just be the ultimate found footage film.

Morrison tells three parallel tales: one in which prospectors expel the Hän people from their land upon discovering gold and start the township of Dawson, another in which the glories and failures of the inhabitants of Dawson help jumpstart Hollywood, and a third one which is nothing less than a history of cinema itself. In the first one we see how at the turn of the 19th century, American prospectors made their way up to the Klondike River territory and drained it from its mineral riches, while displacing the original inhabitants. We learn that over one-hundred thousand people tried making their way up to the Yukon, with over seventy thousand either returning gold-less or perishing on the road. One of those who gave up on the way, but found a way to make money off people’s basic instincts was an ancestor of the current American president, who opened the brothel that started their fortune. Talk about prescience.

In fact, Dawson City seems to have emanated this strange energy that should have made it one of the most influential cultural hubs in modern history, but its distance and the way it was so quickly forgotten once the gold ran out gave it a different future. The small town inspired Jack London to write his books of adventure in the snow. It was also the place where Alexander Pantages opened his first theater before becoming one of Hollywood’s biggest impresarios, and Dawson City paved the road for a young Sid Grauman who realized he had a knack for entertaining people and led him to open one of the most iconic movie palaces in history home to the very first Hollywood movie premiere. It’s as if everyone touched by Dawson City went on to lead a notorious life — and in the case of actor William Desmond Taylor, who worked briefly at the Yukon Gold Corporation before leaving to find fame in Tinseltown, also a notorious death.

The ice and earth of the Yukon held much more stories than the reels of film themselves contained, and one of the most impressive feats in the documentary is how Morrison is able to always find his way back to the central narrative. He’s such an astute filmmaker that he creates dialogues that could very well warrant films of their own, such as the depressing notion that the flammability of nitrate film, which caused fires that burned down Dawson’s entire business district nine times in nine years, was also the reason behind filmmaking pioneer Alice Guy-Blaché’s early retirement. After her studio burned down, she simply gave up. Or how photographs of Dawson City inspired Jim Low and Wolf Koenig to make City of Gold, the 1957 documentary short that originated the “Ken Burns” style of panning and zooming on photographs; therefore originating the form Morrison works with in this very film. The short was nominated for an Oscar and the ceremony that year was held at a Pantages theater.

Morrison proves that there is no better way to tell the story of movies than with movies, and it seems almost spooky how the Dawson City reels supplied him with the material he needed. It’s as if the films had been aching to speak to the world. “Speech” is key here, since all the films are silent. In fact Morrison discovers it was talkies that led so many silent films to be discarded. Dawson City was at the end of a distribution line which meant that films had been out for a very long time before they arrived there, and once their engagements were over nobody wanted to pay the cost of shipping the films back to the studios. In telling this shameful story, Morrison allows the images to speak for themselves. He avoids voiceovers or heavy narration choosing, instead to go with simple title cards, supertitles, and musical accompaniment from Alex Somers’ haunting score. Those who believe in fate might believe Morrison was born to tell this story and perhaps these reels were meant to surface only when he was around to share with the world. Those who prefer pragmatism will undoubtedly be captivated by this tale of progress and its relation to art, but both sides will agree that the stories contained here are nothing if not stranger than fiction.

Dawson City: Frozen Time is now in limited release.