According to Kenji Katagiri’s debut feature Room Laundering — and I have no reason to disbelieve him — Japan has a law stating that landlords must divulge whether a previous tenant died or suffered a violent crime within any newly vacated property to all prospective replacements. But while this rule makes sense considering people are sensitive to the notion of supernatural hauntings and evil spirits, lawmakers never stipulated how long before that history can be “cleaned” off the books. No one setting the duration at “x-amount of years” is an obvious oversight, but that lack of concrete interpretation allows owners to simply agree to a loose understanding hinged upon the basis of the tenants themselves. If someone moves in and leaves afterwards, whomever follows won’t technically have to know.

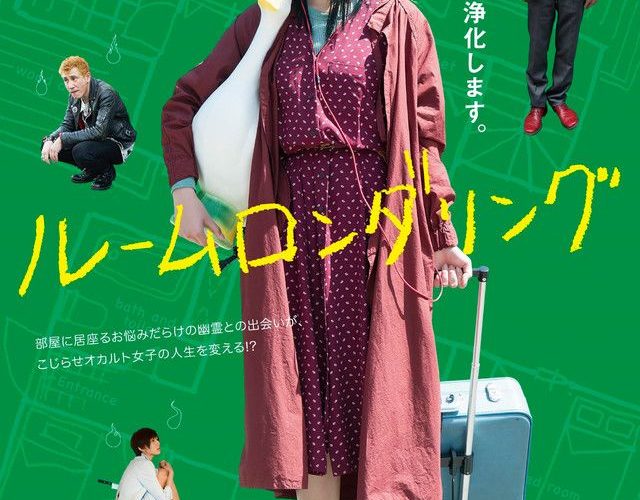

It’s a wild loophole that makes for a captivating premise to set a sweetly funny and surreal coming-of-age tale centered upon a twenty-year old, introverted young woman named Miko (Elaiza Ikeda) who just so happens to be able to see ghosts. After losing her father in a car accident and enduring her mother’s disappearance, a grandmother ultimately raised her before passing away a few years later. With nowhere to go, Uncle Goro (Joe Odagiri) arrives to try and pick up the pieces. He’s also an opportunist, though — one able to turn a new ward into an employee that allows him to become one of their city’s self-proclaimed “room launderers.” So he moves her from suicide flat to suicide flat, wiping the bureaucratic slate for a nice, harmless payday.

What better person for the job? Miko has no friends and possesses no inclination towards making them with a mantra of “no fraternizing with neighbors” constantly upheld on the job. She’s content to sit in silence and draw her roommate spirits in a notebook. There’s little more she can do about them anyway. We assume they left her alone and she reciprocated the favor until her latest cohabitant discovers her ability and refuses to pretend he can’t finally have a conversation. Kimihiko (Kiyohiko Shibukawa) is a punk rocker that slit his wrists and can’t move on, either from regretting the act itself or regretting what he didn’t accomplish before picking up the knife. An affable guy with a funny personality, he slowly chips away at Miko’s fortified defenses.

This then becomes the film’s main thrust. We’re watching as life creeps up behind Miko until she can no longer ignore it. First it’s Kimihiko’s loquaciousness. Then it’s her first murder victim’s (Kaoru Mitsumune’s Yuki) justified rage about why anyone would want to do her harm. And finally it’s a (real) neighbor (Kentarô’s Akito) whose own brand of awkwardness pushes him towards her as she falls back on her default desire to escape. After believing for so long that she was someone people leave, these fresh faces (dead and alive) refuse to let her have a single breath in peace. It unsurprisingly proves an extremely annoying situation for her initially. But their interest and tenacity soon opens her eyes and heart to brand new possibilities.

Katagiri and co-writer Tatsuya Umemoto include a ton of character quirks right down to the waiter at Miko’s local diner resigning himself to just making her usual order since he knows she’ll never speak to him or anyone else with alterations. There are secrets (Does Goro know what happened to his sister and should he tell his niece?), mysteries (Who killed Yuki and can Miko discover his identity?), and gorgeously simple visual cues from the flickering light of her goose lamp marking the appearance of a ghost to her somberly fanciful reaches into the sky to pluck planes out of the clouds with her fingertips. Ikeda portrays Miko with a wealth of embarrassed shyness that endears her before gradually revealing the inherent compassion beneath her otherwise cold façade.

The score is playful and Katagiri’s use of periodic montages a delight that only increases the comedy within Room Laundering‘s underlying, darker themes. Miko may find herself begrudgingly embroiled in an adventure to free the souls of her new friends and come to grips with her ability being a gift rather than a curse, but her general ambivalence (whether an act or not) is welcome as the perfect foil to Kimihiko’s over-eagerness and Yuki’s loud desperation. And if she doesn’t eventually embrace her powers completely by the end after all, the set-up for a young adult (the couple instances of the f-word are audibly bleeped and asterisked in the subtitles) franchise of cases with Miko the detective ghost whisperer is there to follow in Veronica Mars‘ footsteps.

Don’t assume the intentional demographic skew towards teenage audiences makes the whole any less enjoyable for adults, though. Odagiri’s cynical Goro and his nefarious associates keep things interesting while the never-ending stable of rooms to choose from (a stat is shared about how almost one hundred people a day die of suicide in Japan) shroud things with a macabrely melancholic veil since we can always expect authentically tragic circumstances to be unearthed from every boisterous or attention-starved spirit met along the way. Katagiri therefore delivers a wonderfully measured mix of horror-infused police procedural and fairy tale conventions lending a cutely romantic and inspiring tone. Anyone who considers him/herself anxious and withdrawn should appreciate Miko’s tentative evolution from self-imposed isolation to the hard-won acceptance of those earning her trust.

Room Laundering is now playing the Fantasia International Film Festival.