It’s been humanity’s dream since the dawn of time to find the fountain of youth: immortality. To live forever is the ultimate success for humanity’s optimistic idealism. We witness the pain and suffering death creates, constantly trying to distance ourselves from it by forgetting how our lifespans’ brevity makes them special. It’s in death that we see who truly loves us and whom we hold closest. For someone like Marc Jarvis (Tom Hughes) death can even become a celebration. The sting and sorrow a terminal diagnosis delivers sets an expiration date so he can live like there’s no tomorrow after reconciling his reality since there literally is none. Fear often drives our instincts to endure in this moment, but sometimes it also has us hoping for more.

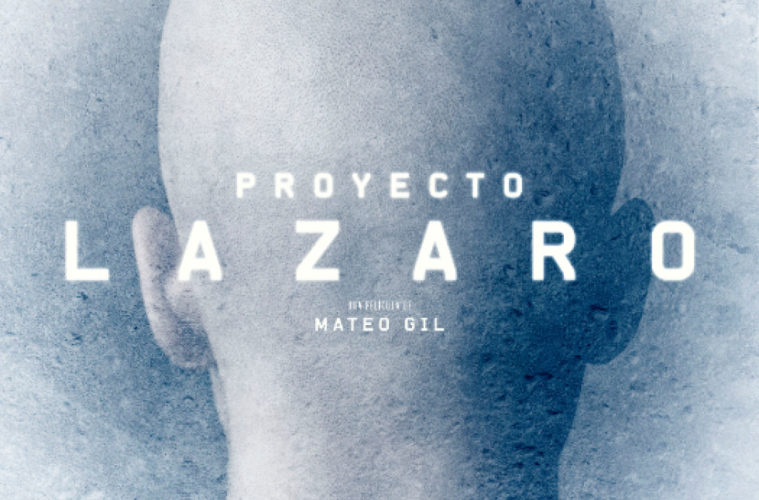

The fact Realive‘s tale of life and death in the face of technological improvement and emotional stability’s existential clash comes from writer/director Mateo Gil should be no surprise to a fan of his work with Alejandro Amenábar. Like Amenábar, whose latest film bowed in 2015, the commercial failure of their last collaboration Agora pushed Gil to the sidelines for half a decade. Why wouldn’t he go back to his greatest successes (Abre los ojos and Mar adentro) for inspiration? Those two films dealt with cryonics and suicide respectively — the pain of living an unwanted life. Marc Jarvis fits perfectly alongside César and Ramón, his vision of perfection impossible when compared with his reality. Death may be an ending, but what if its emptiness is still better than the alternative?

Jarvis has faith that it won’t — or at least the version of him we’re privy to at the start does. He’s seen what cancer and chemotherapy does to a body thanks to his father’s lengthy battle with the disease and wants nothing to do with experiencing the same hardship. Already in 2015 scientists have reanimated flies and shot stem cells into animal organs with success. So why not roll the dice and believe the same things aren’t far away for humans too? He’s as healthy as he will ever remain with inevitable degeneration on the horizon so the time is now to be cryogenically preserved for the future. His girlfriend Naomi (Oona Chaplin) begs to remain by his side throughout the illness, but he’s ready to say goodbye today.

By wielding control over his mortality Marc protects himself from fate. Doctors gave him a year? Screw that, he’s giving himself a month. If he takes his own life now with the cryogenics company on call to pick him up, his cells will be as viable for regeneration as possible. This is his choice and he embraces it. Does he know that in six decades he will actually open his eyes again? No. No one could. Dr. West (Barry Ward) hoped he’d find success after a lifetime of his own struggling to make it happen, but the shock and joy of seeing this once dead cadaver breathe oxygen proves he wasn’t certain he could. Marc’s back: twenty percent authentic with cloned tissue and bio-robotic enhancements supplying the rest.

What does that mean and what truly is the definition of life? These are the questions Gil asks by giving his character exactly what he wanted in a way that he never took the time to realize might be the result. The life West returns to him isn’t the life Marc lost. I don’t mean this physically considering the breadth of artificial tissue composing his body or the mechanical umbilical attached to his stomach. I’m talking the psychological ramifications of being a man out of time. The emotional tumult that comes with assisted living loneliness. Only now that he’s back does he realize the time he lost with Naomi. Possessed by a broken heart that cannot be mended, his soul and love are beyond any laboratory’s reach.

This direction risks Realive becoming a sappy melodramatic romance out of time with regret and guilt, but Gil never lets it get lost in such contrivances. By unfolding Marc’s story simultaneously through the present (2084) and memories of the past (1982-2015) we’re made aware of what is necessary to the plot at-hand. We must understand the life he’s giving up to understand his anger. We must understand the journey taken to acquire Naomi’s long-gone love to understand the pain of heartbreak. We endure the disorientation of new life as Marc does, experiencing the quick flashes of recollection recorded on a “mindwriter” without rhyme or reason until honing his focus. We appreciate his interest in a future devoid of monogamy while relating to his frustration towards irreparable health.

Gil’s utilizing a pragmatic science fiction filter wherein his future retains our present’s hubristic shortcomings of pure fantasy. Just because reanimation is possible doesn’t mean it’s advisable. It’s great to watch Marc’s eyes flutter upon the smiling faces of West, Dr. Serra (Julio Perillán), and nurse Elizabeth (Charlotte Le Bon), but nothing this dangerous and seemingly impossible could ever become a reality without years of disappointments and failure. At what cost to the human race has Jarvis returned? At what cost to his own identity? We yearn to believe in a world where anything is possible and continuously forget about the other side of the scale. Marc sees the futility of his remaining days and looks to cheat it only to discover he cheats life instead.

This is a film of philosophical rumination as its hopeful characters find themselves living in an imperfect world of their own creation. Happy endings aren’t so happy and impossible discoveries arrive as nightmare. Science is about sacrifice much like life and to a certain extent both must learn to embrace the tragic truth of a finite existence in order to sleep at night. The mysterious unknown is mysterious with reason. We cannot anticipate what’s on its way and therefore shouldn’t try and mess with the natural progression of things. To play God is to inherently dissatisfy — just look outside. Life is for the living. All meaning is erased as soon as you lose sight of what you have now to reach for a future that may never be.

Realive screened at Fantasia International Film Festival and opens on September 29.