Last week we saw a film from Pawel Pawlikowski that crossed continents and spanned decades and lasted a mere 84 minutes. With the exception of a devastating climax that skips a few years, the majority of The Wild Pear Tree takes place over just a few days. It is more than twice as long, and, I would wager, has ten times as many lines of dialogue. We are being rather flippant here (it’s been a long week), especially given the fact that the director, of course, is Nuri Bilge Ceylan, hardly a filmmaker known for his concision. He is, however, responsible for Once Upon a Time in Anatolia — a work that seems, as the years glance by, to be gaining the aura of a modern classic. He also made Winter Sleep, which was even longer. It also won the Palme d’Or.

So: in short, this is something certainly worthy of three hours of your life, not to mention the time you might need to digest. We mention Pawlikowski because one could be within their rights to argue that he thinks like a filmmaker, visually speaking, whereas Ceylan thinks like a novelist or a playwright. The protagonist of The Wild Pear Tree is himself a novelist, a young man at a crossroads in life who appears to be grappling with a lot of big ideas.

We are not amongst the rolling hills of Anatolia but in the northwestern Turkish city of Çan. The young man is Sinan (Aydın Doğu Demirkol), an aspiring writer of fiction who is just about to finish university where he, like his father before him, is studying primary teaching. He’s smart, but a bit of a know-it-all and with a personality that’s very much on the serious side. As Ceylan quickly suggests, this might be because his dad does not. The elder, named Idris and played by a sporting Murat Cemcir, is a primary school teacher with an absurd laugh who has a taste for bad practical jokes and, unfortunately for Sinan and his family, the racetrack.

As with much of Ceylan’s work, the majority of The Wild Pear Tree is heavy on dialogue — not in the meandering Richard Linklater sense, but in a more impenetrable, academic way. It is essentially cinema as conversation, and these conversations come in dense chunks, as when Sinan meets a popular local writer and exasperates and antagonizes him with questions about his work or, later (in what is the film’s most exhausting sequence), as Sinan and two old friends walk around eating apples and talking about faith. A lot of the time, this feels like self-reflection. Sinan is constantly attempting to get his book funded by local officials, only to be continuously denied because his work, as they see it, has little value for tourists. Ceylan is Turkey’s most celebrated living filmmaker; we can only imagine similar pressures have been placed on him.

The pear tree is both the name of Sinan’s book and the tree that stands beside a small farmhouse the family owns outside of Çan. We learn that Idris has been attempting for years to dig a well despite the insistence of people from the area that he will not find water. This acts as a neat metaphor for Idris’ dreaming, but perhaps his foolishness, too. This weighing up of life’s expectations and realities will prove to be the film’s devastating key theme.

Pear Tree is nothing if not demanding. I would go so far as to recommend that anyone viewing it should perhaps do so in the early evening so as to leave apt time for digestion, not least if you, like I, happen to not have any grasp at all of the Turkish language. I can hardly think of another instance in the cinema when I had to make an asserted effort to look away from the subtitles simply to see the expressions on the actors’ faces. It is best to have your wits about you, but do not be deterred by that running time. The staggering emotional payoff — a transcendental moment so beautiful in its simplicity that the previous three hours of seriousness appear to melt away — is worth every last minute.

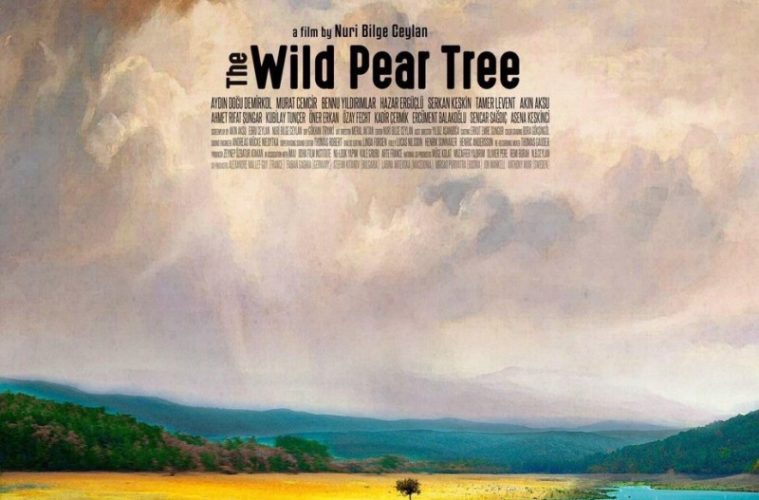

The Wild Pear Tree premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and opens on January 30. Find more of our festival coverage here.