Sometimes it isn’t enough to simply portray the type of eternal love that Shakespeare wrote about in Romeo and Juliet. Watching two star-crossed lovers attempt to fight the injustices of this world to be together, only to sacrifice themselves, can still ring hollow because it hinges upon the naiveté of children not looking for another solution regardless of whether the result would be the same. To take the poison is to admit defeat against external forces that are too strong to fight. Love therefore becomes our sole reason to exist once everything else is shown to be false. Until then we still possess hope and the possibility of improving our circumstances so that our love may be fostered beyond a fleeting fantasy.

Love becomes the byproduct of futility, the single tangible concept we can hug when everything crumbles around us. Love doesn’t therefore kill; it sustains when the rest burns. It comforts in the face of horror, consoles when alone in jail to pay for our sins, and provides clarity towards betrayal insofar as reminding ourselves that we’d have done the same in our betrayer’s shoes. It’s necessary in a society driven by greed for dog-eat-dog justice to the point where an acceptance of consequences is the only feasible response to them. That greed supplies a transparency of motive making it so there’s nowhere left to hide. And punishment becomes an ultimatum wherein those in power leverage our fears and dreams against us as a means for recruitment.

This is The Gentle Indifference of the World as Adilkhan Yerzhanov’s film’s title and the Albert Camus quote on which it is based describes. We’re at the edge of a cliff that delivers apathy upon reaching the ground below as opposed to death. Our lives are an infinity loop of dominoes standing on end that topple and recover until exhaustion and frustration elicits a derisive smirk instead of tears. We shrug at death, our emotional response one of jealousy that the deceased can finally be at peace while we’re left to suffer under the weight of mistakes left behind. We shrug at exploitative propositions, our innocence long-gone and since replaced by a necessity to take one more breath despite its payment being another rock holding us precariously underwater.

And we justify it with love. We tell ourselves it’s only a quick fix we will soon rid our memories of upon reaping the benefits of the sacrifice with the one we made that sacrifice for. We say this knowing full well that it is a lie because the few seconds of freedom it provides is worth the trouble. Some believe they can avoid this line of thinking, but that too is a lie. Just look at Saltanat (Dinara Baktybaeva) and Kuandyk (Kuandyk Dyussembaev) living their provincial lives without a worry about the future. Their peaceful façade proves to be just that when the police come to collect Saltanat’s father’s debts. One mistake brings their house of cards down to reveal the first of many unavoidably “easy choices.”

Guilt enters as her mother speaks of a city uncle (Yerken Gubashev’s Haim) who can help. The trepidation is an obvious tell as far as what that “help” will be and Saltanat’s arrival to a request for marriage on behalf of his business partner (Arken Ibdimin’s Zakir) cements as much. But she decides to refuse — an example of free will that’s less empowering as it is crucial to learning she has none. The same can be said for Kuandyk using his fists to serve his new employer (Teoman Khos’ Aman) so that he can in-turn use his wages to support his unrequited love. Its sense of accomplishment is short-lived too, however. Eventually another domino falls to present another impossible choice to shrug at once self-preservation overpowers morality.

It’s this shrug that will haunt you while watching. It’s the sudden ease at accepting one’s fate with a disapproving glance back or defeated nod of agreement rather than anger that exposes how bad things have gotten. Depravity is one thing, but consent towards one’s own destruction is another. That awareness is what makes us cringe because we know it too well. We constantly find ourselves in situations where keeping our mouths shut or throwing someone else under the bus presents a windfall. At first we reject the idea that we could do such a thing and then we do with back against the wall. It only becomes easier afterwards — a realization that either confirms we’re too far-gone or smacks us awake to take a stand.

Yerzhanov and Roelof Jan Minneboo’s script is full of these forks in the road for Saltanat and Kuandyk to choose a path. Sometimes they pick the right one and other times they don’t. The former allows them to risk getting closer while the latter makes it hard to even look the other in the eye. We watch as Kuandyk’s confidence falters, his strength dissolving into quiet apology. Parallel to that is Saltanat chopping up her soul to trade pieces for those she loves, each loss pushing her closer to the callousness necessary to laugh in the faces of those who’ve stolen her innocence while wringing their own hands in self-loathing. We learn to care for these two only to watch how such feelings ultimately bring nothing but pain.

But that pain arrives on the back of a beautifully shot, subtly funny picture meticulously composed to juxtapose Kazakhstan’s rural expanses with its claustrophobic urban landscapes. Characters move within static frames to add suspense whether two villains moving towards the darkened interior of shipping container behind Kuandyk or Saltanat coming into view to approach her cornered mother on a jail cell bench. Oftentimes action occurs completely off-screen so that we only see the bloodied result — what truly matters since our coldness towards human life besides Saltanat and Kuandyk is quickly formed. By the end we willingly stand-by as they do what they must to escape. It may render them unrecognizable alone, but their youthful exuberance remains intact when together. Romance doesn’t need a kiss when unyielding devotion exists.

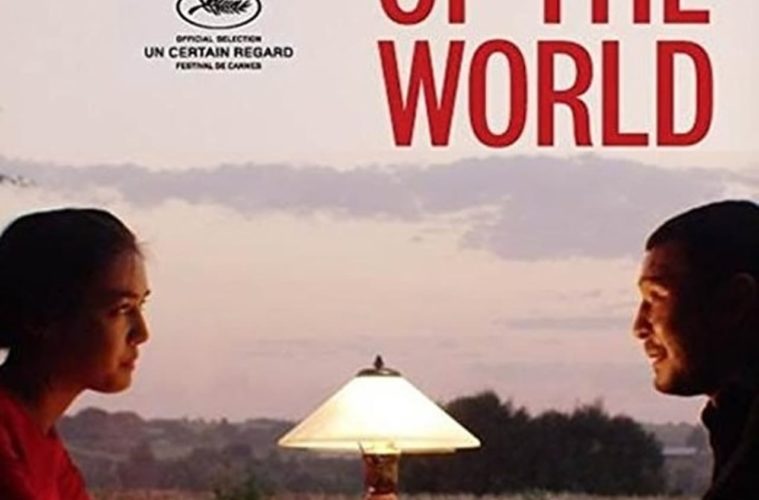

The Gentle Indifference of the World premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. Find more of our festival coverage here.