In Wes Anderson‘s seventh film Moonrise Kingdom, the quintessential quirkiness that’s made the filmmaker a household name is in full effect. Unlike his last live-action and somewhat somber film The Darjeeling Limited, this is a return to the youthful vigor and real emotion on display in his earlier work. The film acts as a metaphor for the innocence of childhood, while also embodying and distilling what it feels like to be in love for the first time. These are universal traits that will undoubtedly appeal to the cinematic multiverse of global audiences. That said, the grin-inducing charm that Anderson seems to elicit so effortlessly here feels like little more than “par for the course” in his pantheon of quirky filmmaking.

After a virtuous series of dolly shots vividly paint a family portrait over the opening credits, our Narrator (Bob Balaban) sets the stage for a fictitious island off the coast of New England in 1965. A troop of khaki-wearing boy scouts led by Scout Master Ward (Edward Norton) awaken to find that one of their troops has disappeared, leaving behind only a note of resignation from their group. The scout in question is a resourceful orphan named Sam Shakusky (Jared Gilman), who has embarked on a mission to reunite with a girl he’s smitten with, one Suzy Bishop (Kara Hayward).

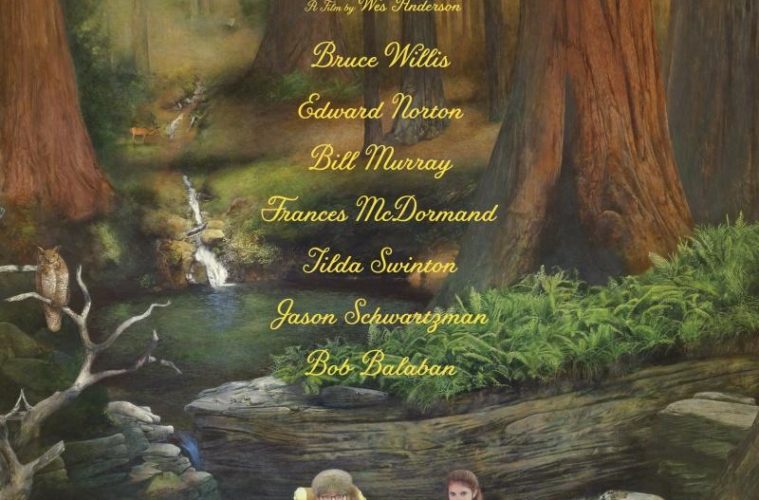

They met by chance during a theatrical performance of a Rushmore-esque re-telling of Noah’s Ark, which triggered a subtle romantic connection. After remaining in correspondence for almost a year as pen pals, the duo run away to escape the adult world and in turn elicit a search party comprised of Suzy’s lawyer parents Mr. (Bill Murray) and Mrs. (Frances McDormand) Bishop, a bumbling local cop (Bruce Willis) and a social service worker known only as Social Services (Tilda Swinton).

As the fellow scouts that join the pursuit of the star-crossed fugitives, the film becomes more and more fantastical. Their journey starts to resemble the storytelling of childhood books that Suzy reads to Sam at night, the same tales Anderson hopes you’ll go out and read after the film. And though the film grows increasingly ludicrous and whimsical, Anderson continues to successfully distill the purity of young love while balancing the wonder of what it means to be a child. There are some dark thematic streaks on display as well, but they tend to be buried by the outlandish tone bursting out of the mise-en-scene.

The vintage decor, music and color palette of the 1960s era seems almost too perfect of a marriage for Anderson’s own idiosyncratic tropes. From battery-powered record players to a whimsical tree house far too high up to be safe, there is a definite sense of immersion in this magical world. Yet Moonrise Kingdom does little to distinguish itself from Anderson’s other work and will likely not garner him any new fans.

The vintage decor, music and color palette of the 1960s era seems almost too perfect of a marriage for Anderson’s own idiosyncratic tropes. From battery-powered record players to a whimsical tree house far too high up to be safe, there is a definite sense of immersion in this magical world. Yet Moonrise Kingdom does little to distinguish itself from Anderson’s other work and will likely not garner him any new fans.

Audiences who already appreciate the inherent visual neuroticism that Anderson toils over in every delicately-composed shot will praise this ensemble film as the second coming of The Royal Tenebaums while newcomers might be more wary of the overly niche style. Still, there’s no denying the effervescent charm that makes this auteur’s style of filmmaking so unique and compelling, and in that sense Moonrise Kingdom fits the bill.

Moonrise Kingdom opens on May 25th, 2012.