While you can debate the success of politically motivated events like 1970’s October Crisis in Quebec, Canada, you can’t question their danger removed from the cause. The media reports the carnage whether terrorist bombings or kidnappings and murder. They provide an objective account of what’s happening—in this case the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) wreaking havoc to force secession from the country and become an autonomous nation—and leave it to their viewers to understand the context. Adults can handle this because many already have an opinion one way or the other. But children don’t. Children only see their parents’ reactions and the aftermath. If they’re led to understand violence can achieve one’s goals, they might follow suit when their own backs are against the wall.

This is an interesting wrinkle many forget with rebellion proving much more palatable. Artists generally gravitate to the drama of those entrenched in the fight, commenting on the politics, courage, or sheer madness driving each character. By contrast, novelist Nicole Bélanger takes a step back to craft a desperate scenario many people face whether their homes are ground zero to martial law or not. She shifts focus away from the activists, nationalists, and authorities attempting to maintain peace between them and instead places it onto a young girl with more pressing personal issues at the forefront of her mind. This doesn’t mean that what the FLQ is fighting for doesn’t concern Manon (Milya Corbeil-Gauvreau), though. On the contrary, Quebec’s precarious position plays a huge role in her strife.

The October Crisis was fought because of wealth disparity and a suppression of voice. Manon’s family is on the lower end of this scale with parents barely scraping by before getting hit with tragedy. First comes our assumption of unemployment, next is Dad’s cancer diagnosis without insurance to cover the costs, and finally it’s Mom succumbing to the pressure coping with all this while caring for two young kids supplies. The girl’s uncle and aunt do what they can, but it’s difficult with three children of their own. So rumors fly about foster care. The seed is sown that Manon and her little brother Mimi (Anthony Bouchard) will be separated and removed from their home. It may be the best option for them, but she refuses to acquiesce.

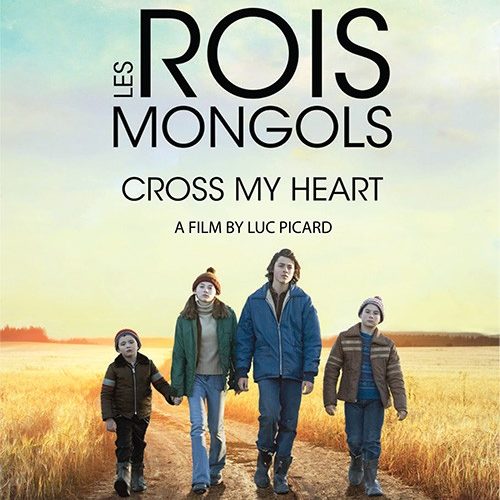

Bélanger’s Cross My Heart places this teen’s plight against the chaos of LFQ ransom demands being honored on television while Anglo soldiers arrest the opposition in her streets. She draws Manon at a time of social upheaval wherein drastic times call for drastic measures. So with the help of her cousins Martin (Henri Richer-Picard) and Denis (Alexis Guay), she hatches a plan to kidnap an older, wheelchair-bound woman (Clare Coulter’s Rose) in order to escape the social worker’s inevitable arrival with irrefutable leverage. They’ll take this woman, demand to be left alone, and ultimately become the happy family their parents, the government, and God himself refuse to provide. The result is an alternately funny and poignant look at the anguish no child should ever know.

Director Luc Picard brings it to life with period detail that transports us into the 70s. He and the cast do Bélanger’s words justice by allowing the complexities that propel Manon’s simple yet naïve plan forward to resonate even as the “big picture” becomes a punch line to the smaller, crucial one. You can’t help laughing upon realizing how close to FLQ rhetoric Manon skews. When she signs her ransom note “The Family Cell,” she becomes a legitimate threat. When Martin and Denis’ older, radicalized brother Paul (Gabriel Lemire) goes missing, they become presumed collateral damage. Nothing could be better for Manon’s plan because this confusion obscures their scent. With a false sense of urgency, however, also comes the potential for punishment too swift to recognize the truth.

So there is an effective sense of suspense even if it runs just below the surface. I actually like it this way because you don’t realize how worried you are about the characters until it’s too late. The humor deflects the tension. A surprising turn of events concerning their relationship with their victim does too. We become lulled into a false state of security, wondering if somehow everything will turn out right because the police are too busy to worry about a few runaways. The way Bélanger and Picard wield this power to shield us from the harsh reality check of life soon to come is fantastic. They constantly remind us how young their perpetrators are to earn our sympathy despite “innocence” being a dubious argument at best.

It’s not without missteps, though. These occur in the transitions with an oddly jarring use of music that often cuts off abruptly for added impact. I think Picard does this to present the duality between kids utilizing terrorist tactics and the severity of the tactics themselves, but it happens before acknowledging that division is necessary. The flourish occurs a couple of times out of nowhere with a happy-go-lucky mood screeching to a halt so the subject and tone can change before we even know what hits us. It makes some of the first two-thirds feel choppy, but no less effective in the content itself. We still understand what is happening and open ourselves up to the characters’ plight. The journey is just less smooth than you may expect.

Despite some sensory issues, you cannot fault the actors or the authenticity of place. When these kids do something “adult,” they do it as kids trying to impress or from sheer desperation. They act out of love whether familial or otherwise (the romantic undertones between cousins Manon and Martin are intentional), each quite possibly willing to give his/her life for another. Their “cell” is to their family what the FLQ is to Canada—an impatient and underrepresented contingent of voices struggling to be heard. No one asked Manon and Mimi if they wanted to be separated from their parents. No one asked if they could survive apart from each other. And they’re forced to do some bad things upon finding themselves in over their heads because they’re fighting a war.

Cross My Heart premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival.