From Sophie’s Choice to My Sister’s Keeper, child loss has been the subject of everything from prestige Oscar pictures to YA drivel. It’s an understandable focus, for there are few more intrinsically emotional narrative foundations than parents coping with the loss of a child. And whether those characters are together or separated, that loss serves as both a shared crucible and a uniting force.

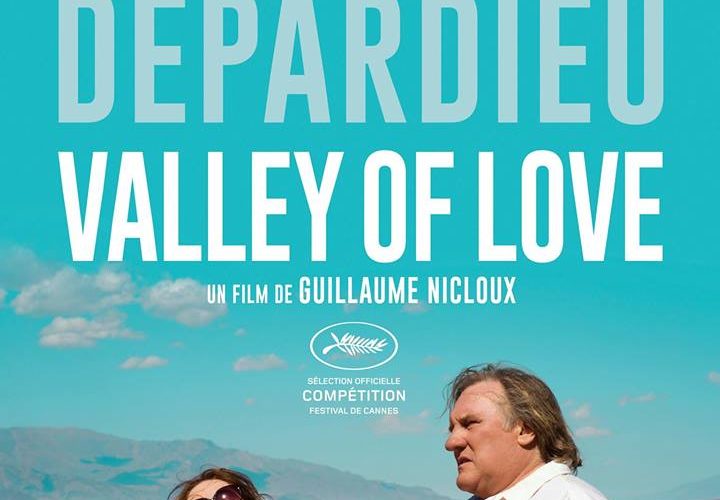

Guillaume Nicloux’s Valley of Love pares this scenario down to its most elemental sediments, brings in two international superstars with a loaded onscreen history, and the rest nearly takes care of itself. Valley of Love lives and dies on the caliber of its actors, and the film is certainly in good hands with Isabelle Huppert and Gérard Depardieu, two performers who haven’t been together since Maurice Pialat’s Loulou but have careers that, together, span every major auteur constellation across the globe.

Nicloux goes farther in mirroring reality, even presenting Huppert and Depardieu as actor facsimiles named Gérard and Isabelle, akin to Juliette Binoche’s elongated refraction in the recent Clouds of Sils Maria. But Nicloux is less concerned with constructing a reality of self based on a fluidly passing sense of time as much as looking at these characters from a fixed vantage point. Years have passed, and they hardly know each other’s eating habits, let alone how to have an extended conversation without clawing at each other’s throats.

But this isn’t merely an excuse to replay a Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf -esque scenario of looping torment. Rather, it’s a searching examination about a failure to know another person, and what it means to believe as both its own reward and as a show of faith to another person.

As the film begins, Isabelle and Gérard are separated and haven’t seen each other for years. That changes when their son, Michael, mysteriously commits suicide, sending letters to each of them that contain directions to meet at each of the seven Death Valley landmarks based on a precise time table. Gérard is a resolute skeptic, believing these instructions to be some sadistic penance for his failures as a father, but Isabelle wants to believe that there’s something transcendent coming.

Their individual letters are unsparing, containing criticisms that are everything short of outright blaming them for his suicide. Michael unflinchingly synthesizes his memories of his mother as “anxious,” while his most prominent perception of his father relates to a characteristic look of “disapproval.” Mutual reflection ensues as Isabelle and Gérard wonder how so much time has passed and how they know so little about the people around them. When Isabelle asks Gérard about how his daughters are doing, he can’t help but avert his glance in grave recognition that some potential relationship is far back in the rearview.

Mortality is certainly one of the most consistent discussions — one of the characters is waiting on news that places some of the narrative’s pieces into vastly different contexts. As their conversations volley back and forth, Huppert and Depardieu have a singular talent with body language, Huppert imbuing each sentence with such immediacy that she looks like she’s bracing for impact. There is one point in her performance, involving a hotel room, that doesn’t feel totally convincing, but it’s more a case of a single point in the story feeling dramatically irregular than a hitch in Huppert’s skills.

Nicloux’s direction knows to never get in the performers’ ways, favoring close-ups during extended dialogues between the players and amplifying Death Valley’s voluminous basins with frames that surround Huppert and Depardieu with negative space. An image in particular, of Depardieu and Huppert side-by-side over a canyon with an umbrella, finds a perfect contrast between the soothing grays over the ridge and the kitschiness of their American clothes to communicate an alienation from this location. The two players’ elegance shines all the way through.

The American backdrop in general lends itself to a decent amount of “fish out of water” comedy, namely with a terribly cringeworthy discussion where Isabelle and Gérard are forced into a bar discussion with a few Americans who are slightly familiar with their films. Soon, they’re being interrogated about how Al Pacino acts behind closed doors and if Gérard will take the time to read some aggressively friendly fan’s short story. There’s also some room for tinges of American-flavored absurdism, such as a scene involving an animal head, but it all feels a bit flabby when compared with the consistently insightful and carefully modulated conversations.

Valley of Love is an excellently crafted film, but the main reason to to see it comes down to the interplay between two of our finest living actors. Decades into their career, they’re playing characters that simulate the circumstances of their own lives, but it’s less a performance than an extension of their personas, tucking together larger questions about mortality within the universes of their own sizable careers.

Valley of Love is now in limited release.