At one relatively indeterminate point in The Wolf of Wall Street‘s lengthy, fuzzy chronology — 150 minutes? six years? — a plane explodes, hurtling the burned corpses of three human beings (or what still exists of them) into a stormy night. The event is purposely played as an afterthought while it actually occurs, for as little as it could be said to “occur” all the same: a seagull flies into the plane’s engine, your charred body is catapulted into a violent, raging sea, and the rich, possibly drugged-up handsome man — the man who had very directly sent you there — goes back to his more-beautiful-than-any-human-you’ll-ever-meet wife, relaxing on a boat full of Italians who drink wine while dancing to Umberto Tozzi‘s “Gloria.” So it goes.

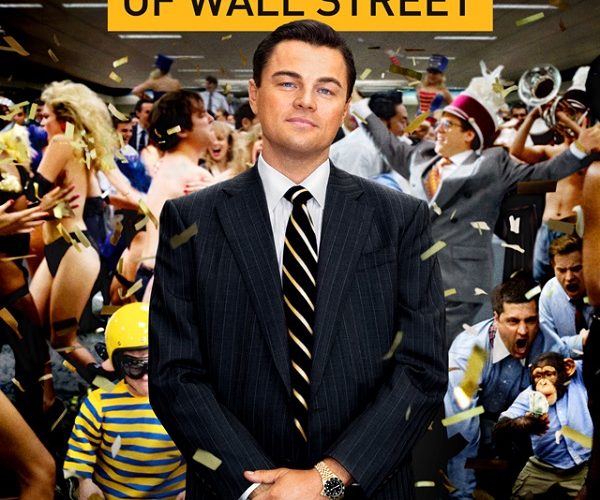

If this interstitial moment’s on-paper description sounds (in no particular order) mean, unsettling, excessive, more than a little bit funny, and, in the case of our protagonist’s other half, even somewhat seductive, it might be best to dispense with other pretensions and simply note (or forewarn) that the newest Martin Scorsese picture is a massively enjoyable experience writ on an absolutely exhausting landscape. Maybe that latter quality won’t prove some big surprise: the long run-up to its release has engendered much burdensome discussion of a three-hour runtime. Bolstered by its high-budget, independent financing and production, the film’s overriding sensibility can perhaps be most eloquently summarized as “fuck you.”And maybe you, too, will take this seemingly unending, absolutely relentless plunge of a picture as something of a “fuck you,” having viewed a gleeful scorning of characters that’s played to a degree that can only demand a viewer’s surrender, and will, if necessary, only accept their defeat.

If this interstitial moment’s on-paper description sounds (in no particular order) mean, unsettling, excessive, more than a little bit funny, and, in the case of our protagonist’s other half, even somewhat seductive, it might be best to dispense with other pretensions and simply note (or forewarn) that the newest Martin Scorsese picture is a massively enjoyable experience writ on an absolutely exhausting landscape. Maybe that latter quality won’t prove some big surprise: the long run-up to its release has engendered much burdensome discussion of a three-hour runtime. Bolstered by its high-budget, independent financing and production, the film’s overriding sensibility can perhaps be most eloquently summarized as “fuck you.”And maybe you, too, will take this seemingly unending, absolutely relentless plunge of a picture as something of a “fuck you,” having viewed a gleeful scorning of characters that’s played to a degree that can only demand a viewer’s surrender, and will, if necessary, only accept their defeat.

That The Wolf of Wall Street should come across as a full opportunity for its helmer to show off — would you like the longest, craziest drug-taking sequence known to man? here it is! would you like our climactic crumble to supplant The Graduate for cinema’s best use of “Mrs. Robinson”? here it is! (this is to say nothing of the use of “Hip Hop Hooray,” the context of which is best kept a surprise) — makes for much of “the point,” as you might be content to label such things. Like the finest character studies which have come before, Scorsese and scribe Terence Winter (here adapting real-life subject Jordan Belfort’s eponymous memoir) configure topic and projection as essentially synonymous. They glide seamlessly from a one-step-removed introduction — this terrible, nearly incomprehensible commercial for Belfort’s brokerage firm that practically starts as an act of subterfuge, more or less sneaked in amongst corporate logos — into three continuous hours of a shifting, tiring construction primarily operated by the voice of its own central figure. The two-pronged starting gun — “well, no, the Lamborghini I drove while being fellated by my stunning wife wasn’t that color; allow Marty to change its tone in the middle of this complex shot snaking across highway lanes” (again, “showing off”) — is from a protagonist and artist, doing nothing if not telling us how we’re supposed to observe.

Because while the debaucheries of well-dressed brokers need not strike anyone (particularly the picture’s target audience) as any considerable “surprise,” Wolf’s perspective on the matter is singular. This is not at all unlike our window into Travis Bickle’s scummy, inexplicably small-scale New York City, for the design of Jordan Belfort’s entire world — from Wall Street to the Hamptons to Switzerland to the Italian coast — cannot belong to anyone but he and he alone, just as any authorial connections to that 1976 classic would suggest its very creation is elemental to Scorsese as a film artist. It’s a place where drugs, cars, and the stunning women flitter in and out of a frame, only to circle back, practically at one man’s will; it’s a place where these activities, for years at a time, can be indulged with no consequences that are not of some immense benefit for himself; and it’s a place where FBI agents, his one true nemesis, will primarily appear in wrinkle-highlighting close-up or full-bodied, plain-clothed compositions, even as they finally take him down in the middle (and, speaking literally, through the lens) of a vanity act.

Because while the debaucheries of well-dressed brokers need not strike anyone (particularly the picture’s target audience) as any considerable “surprise,” Wolf’s perspective on the matter is singular. This is not at all unlike our window into Travis Bickle’s scummy, inexplicably small-scale New York City, for the design of Jordan Belfort’s entire world — from Wall Street to the Hamptons to Switzerland to the Italian coast — cannot belong to anyone but he and he alone, just as any authorial connections to that 1976 classic would suggest its very creation is elemental to Scorsese as a film artist. It’s a place where drugs, cars, and the stunning women flitter in and out of a frame, only to circle back, practically at one man’s will; it’s a place where these activities, for years at a time, can be indulged with no consequences that are not of some immense benefit for himself; and it’s a place where FBI agents, his one true nemesis, will primarily appear in wrinkle-highlighting close-up or full-bodied, plain-clothed compositions, even as they finally take him down in the middle (and, speaking literally, through the lens) of a vanity act.

The perspective is Belfort’s, and the arrogance which sells this perspective belongs to Leonardo DiCaprio, whose least self-conscious performance yet is all the more odd for being the continuation of a director-actor pairing that’s spent more than a decade predicated upon a certain performative self-consciousness. If one continues to note the much-identifiable tactics of Leonardo DiCaprio, actor — those I’ve-trapped-you-in-a-corner methods of peaking a person-to-person conversation, or the way his shouts of both joy and sorrow sound as if they’re coming from some deep, primal place — they’re still recontextualized by Jordan Belfort, character; to tell how much is pure feeling and how much is the result of a Quaalude likely ingested between scenes is a thornier issue.

To reach as far back as the mostly unknowns of Who’s That Knocking at My Door would rather strongly argue for Scorsese as American cinema’s supreme orchestrator of ensembles, a title which Wolf’s structural and narrative patterns will both support and play against. The film is more keen to position DiCaprio and Jonah Hill — the latter’s Donnie Azoff acting as right-hand man to Belfort — for lead players who transform proceedings into some strange, filthy buddy comedy; their scenes sing, but a large percentage of enjoyment may come from no more than the unconscionably strange sensation of this pairing, their unlikely bond an equal-part result of off-kilter casting and otherwise-incompatible onscreen types. It’s with this that the remaining team are somewhat akin to instruments in a grand piece of music, from the starting keys (Matthew McConaughey) to the enticing flourishes (Margot Robbie) to the underlying accompaniment (more or less Belfort’s entire “crack team,” a wonderfully deranged Jon Bernthal standing out) to the crashing sounds of a finale (Kyle Chandler, whose face [Scorsese’s central visual focus for the man] just seems to belong to a government agent).

To reach as far back as the mostly unknowns of Who’s That Knocking at My Door would rather strongly argue for Scorsese as American cinema’s supreme orchestrator of ensembles, a title which Wolf’s structural and narrative patterns will both support and play against. The film is more keen to position DiCaprio and Jonah Hill — the latter’s Donnie Azoff acting as right-hand man to Belfort — for lead players who transform proceedings into some strange, filthy buddy comedy; their scenes sing, but a large percentage of enjoyment may come from no more than the unconscionably strange sensation of this pairing, their unlikely bond an equal-part result of off-kilter casting and otherwise-incompatible onscreen types. It’s with this that the remaining team are somewhat akin to instruments in a grand piece of music, from the starting keys (Matthew McConaughey) to the enticing flourishes (Margot Robbie) to the underlying accompaniment (more or less Belfort’s entire “crack team,” a wonderfully deranged Jon Bernthal standing out) to the crashing sounds of a finale (Kyle Chandler, whose face [Scorsese’s central visual focus for the man] just seems to belong to a government agent).

There are other directorial comparisons which prove more problematic, and I’m of the mind that at least one needs to be addressed if the film is discussed at any length: its dive into an underworld (albeit one of a semi-public character) has already raised (sometimes sight-unseen) comparisons to Scorsese cornerstones Goodfellas and Casino, but this application, while immensely obvious, might only suggest a reading that forgoes an actual dive into The Wolf of Wall Street‘s true workings. I wouldn’t go so far as to consider this picture superior to that 1990 mob epic, but its particular lens on events is far different and, even, more inherently “interesting” for the overwhelming utilization of formal tactics in providing a specific, personal point-of-view: to be absolutely drenched in non-diegetic music cues — and, yes, extensive, drug-fueled slow-motion images — are but one essential component, these flourishes carried by Thelma Schoonmaker editing that alternates between cutting to the bone of a scene or allowing one to play out in long, almost-agonizing stretches built upon their own alternations of ecstasy or agony.

But because the similarities to more straight-down-the-line rise-and-fall tales are nevertheless evident (narration included), there are going to be a litany of reactions which accuse this film of amorality; the problem, broadly, is that Wolf‘s calibration is so specific that arguments mounted in favor of such a reading may be a by-default misguided take, for they suggest a perspective which Scorsese and Winter almost want a viewer to buy into. Henry Hill’s arrest was a moment of defeat, even something of a wish for suicide; Jordan Belfort’s inevitable fall is not played as a gag, but a gag inside a gag that’s only further accentuated by hubristic behavior which cannot be ceased in even the worst of situations.

But because the similarities to more straight-down-the-line rise-and-fall tales are nevertheless evident (narration included), there are going to be a litany of reactions which accuse this film of amorality; the problem, broadly, is that Wolf‘s calibration is so specific that arguments mounted in favor of such a reading may be a by-default misguided take, for they suggest a perspective which Scorsese and Winter almost want a viewer to buy into. Henry Hill’s arrest was a moment of defeat, even something of a wish for suicide; Jordan Belfort’s inevitable fall is not played as a gag, but a gag inside a gag that’s only further accentuated by hubristic behavior which cannot be ceased in even the worst of situations.

The Wolf of Wall Street speaks loudly for itself as a film that intends to entertain, but the thing proves far more reserved about this one essential element, as overriding as it may still be: it’s an instance wherein unfettered, gussied-up presentation is heavy criticism, and however many drug or sex montages one wishes to lobby as detrimental don’t fully speak to what’s being angled toward from the very outset. How half-brained masculine and economic mentalities are channeled to a mutual, logical, terrible climax in one of the year’s more terrifying final shots is what’s truly essential; how they’re fully, ecstatically sustained over the course of three hours is what ultimately seals Scorsese’s picture as a triumph.

The Wolf of Wall Street will open on December 25.