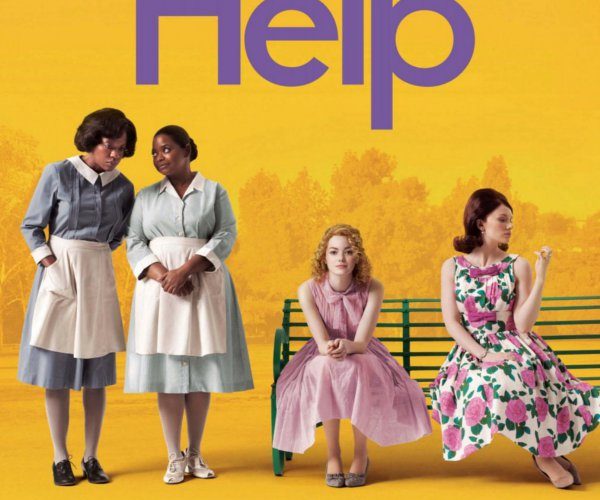

Based on the popular novel by Kathryn Stockett, The Help is a tale of friendship and self-discovery set in the midst of the Jim Crow South — or more specifically 1962, Mississippi. It’s a time where white families of privilege were expected to employ at least one servant, who is almost always black, but were not expected to treat these women — who essentially raised their children — with any semblance of respect. Here the status quo is personified by a cruel young wife and mother named Hilly Holbrook (Bryce Dallas Howard); she is pert and pretty, white, Christian, upperclass, and driven by an insatiable sense of entitlement. She is also an unabashed racist and high-strung terror, who regularly reminds the help of their inferior stature. In contrast to horrifying Hilly is her childhood friend Skeeter (Emma Stone), one of the few white women in the town who recognizes and appreciates the role her nanny played in her life. When she returns home from college — where she scandalously sought an education instead of a husband — Skeeter is astounded to find that her family’s longtime maid/nanny Constantine (Cicely Tyson) is gone. Her mother shrugs off this dismissal, but Skeeter’s love of her missing mother figure soon drives her to see the devastating double standards that surround her and the help. And really, though Stone gets top billing and achieves admirable dramatic turn, hers is only a supporting character, as this story is actually about the overlooked women who do the dirty work in these gleaming Southern homes.

As the film begins, a woman’s voice – resigned and thick with experience – lulls out the introduction. This is Albileen Clark (the stunning Viola Davis), mourning mother, maid to a prissy and neglectful white woman, and caring nanny to her pudgy (and thus unloved) little girl. She is our protagonist, and wins our loyalty early on by soothing her chubby charge, rocking her and gently cooing, “You is smart. You is kind. You is important.” This mantra is meant to weave its way in and fight off all the cruel comments her mother is sure to deliver. Through Davis’ understated and grounded performance, the weight of Albileen’s struggles is easily apparent through her eyes, which are weary but kind. She shows impressive restraint about the casual to aggressive abuse she suffers at the hands of her employer – that is until she joins her dear friend Minny Jackson (a scene-stealing Octavia Spencer) in sanity-saving venting sessions. Minny, maid to Hilly herself, is not one to suffer fools and enacts a retribution that proves revenge is a dish best served cold. Yet for all that the cruelty and injustice these women endure, they refuse to be destroyed by it. It’s this that inspires Skeeter to collect their stories, to show the world what it’s like for them. Give a voice to those who are thwarted the right to speak. (Literature promoting equal rights between the races was illegal in some parts of the South at this time.) So, slowly, the help begin to unfold their tales. And these stories are at times joyful, at times defiant, at times tragic, but always compelling.

Tate Taylor, who previously directed the largely unwatchable comedy Pretty Ugly People, adapted the novel into a screenplay, and then directed a drama that — in spite of its bleak and shocking subject matter — manages to feel warm and life-affirming. This is in part thanks to the stellar cast, stocked with some truly astounding actresses. Stone, best-known for comedic turns in Superbad and Easy A, handles the drama nicely, convincingly playing an outsider who still feels tugged by her mother’s more traditional expectations. Allison Janney takes on this pushy mother who bellows, “Your eggs are dying! Would it kill you to go on a date?”, and would have felt hollow in the hands of a less skilled actress. More solid supporting turns are offered by Sissy Spacek as Hilly’s brassy mother, Jessica Chastain as the new money bride Celia Foote, and Bryce Dallas Howard as the biting Alpha-female. But again, it will be Davis and Spencer that have everyone talking. Viola Davis has drawn notice before (most notably for her shattering and Oscar-nominated performance in 2008’s Doubt), and here she crafts a delicate and layered performance that may well be one of the year’s best. But it is Octavia Spencer who walks off with the movie. Until now, Spencer has largely been a “that guy” actress, having appeared in plenty of well-known films, but often in paltry roles. In The Help, Tate gives her the opportunity to shine, and she does so with a sharp wit, a powerful zeal and a biting sense of humor. Onscreen, the two craft a friendship that feels lush and layered, creating an electric cinematic experience that is sure to draw each accolades come award season.

Sadly, it’s likely the film’s warm tone may thwart Taylor from similar recognition. Yet there’s something sophisticated beneath this palatable and light veneer: a clear sociopolitical commentary. With Hilly Holbrook being as cartoonish a villainess as she is, it’s obvious Taylor is striving to undermine her opinions – showing them to be small-minded and foolish. With her pronouncements of being guided by her Christian faith, and supposedly selflessly concerned for the welfare of the children, it seems Taylor is drawing a clear comparison to a more modern fight for civil rights, and asserting that today’s Hilly Holbrooks will someday soon be recognized as ridiculous and bigoted as this fiery redhead with a shit-eating grin. And it’s this kind of commentary that elevates The Help from the ranks of middling contemporary literature adaptations aimed at women, where some star power and a sentimental plot are often all that is offered. Thankfully, The Help offers so much more. Aside from the gripping performances, it is in turns stirring, funny and insightful. An utter delight full of life, heart and vibrancy, it brilliantly reflects the boldness and bravery of these captivating characters and the real women they represent.