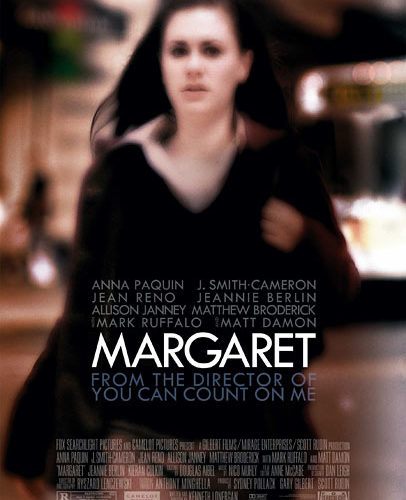

Kenneth Lonergan‘s Margaret feels both incomplete and uncut. What lives on the screen arrives like the bullet points of a much larger, much grander, impossibly longer version of the same basic story: a pseudo-intellectual teenage girl whose life, full of adolescent semi-dramas, is turned upside down when she witnesses/causes a tragic bus accident that takes a life. In the aftermath of the incident, she makes a mistake she’ll spend the rest of the film trying to reconcile. With everyone. The bus driver (Mark Ruffalo); her mother (J. Smith-Cameron); her amiably neglectful father (Lonergan); the victim’s best friend Emily (Jeannie Berlin); her young, attractive private school teacher (Matt Damon) and so on and so on.

Most all of these adults see an over-privileged, over-dramatic teenager and, to that point, a lot of this film feels like the work of an over-privileged, over-dramatic filmmaker. Scenes in upper west side classrooms in which Lisa (Paquin) and her classmates discuss world politics and the motivations of terrorism go on for decades at a time, the teachers in the film looking as exasperated as the majority of the viewers.

But then this is what many in-class high school debates feel like. Likewise, when Lisa goes off on one of her many rants to her mother or anyone else willing to listen (re: turn their head in her general direction) they go on and on and on, repetitious as a stutter. But then we’ve all had brothers and sisters and friends who were that age and would not shut up about the political crusade of the week. Maybe that was you. Maybe it still is.

But then this is what many in-class high school debates feel like. Likewise, when Lisa goes off on one of her many rants to her mother or anyone else willing to listen (re: turn their head in her general direction) they go on and on and on, repetitious as a stutter. But then we’ve all had brothers and sisters and friends who were that age and would not shut up about the political crusade of the week. Maybe that was you. Maybe it still is.

Lonergan and editor Anne McCabe struggle with the footage shot and how to place it in the narrative. In this way, the film feels immensely disorganized. A shot of a notebook on Lisa’s bedside table lasts for 12 frames, then never returns. A shot of a door shutting is followed immediately by the next day, begging the question: what door was shut and why? That said, it seems a motif McCabe and Lonergan hope to achieve here is a sense of realism by way of anti-narrative. No scene ends the way it’s meant to. The pacing of everything is off. A character masturbates seconds before attempting to offer sage advice. A dying woman quips about the nature of her impending death the moment before she calls out for her daughter. These parallels are painful to watch, yet so easy to relate to. Where other films take out the “fat,” this film wades in it and presents it as story. Of course, this can only go so far. Something has to give.

Characters are introduced and given a place in the narrative, then disappear. Such is the case, in particular, of Darren (John Gallagher Jr.), a good friend of Lisa’s who hopes to be more than that but doesn’t know how to court the young girl. His struggles remain on the edge of the film. These subtractions suggest that Lonergan and co. were perhaps not willing to part with even some of the slow-motion, awkwardly-framed b-roll of people walking the streets of New York in lieu of more character development. On the opposite end of the spectrum, Jean Reno‘s foreign Lothario character takes up far too much screen time, offering inappropriate comedy in all the wrong places. It’s decisions like this that ultimately prevent this film from achieving what is its ultimate goal: a full-scale dissection of the teenage psyche as juxtaposed with the adult psyche.

For a film about a bus accident, it’s remarkable how little of the film concerns the event. This is a two-and-a-half hour long character study. Paquin – who’s almost another person these days thanks to her busty, blonde True Blood persona – plays teenage confusion at a perfect pitch. The daughter of a self-absorbed theater actress, she fights against her genetic need for center stage while fully embracing it. As the film progresses, each adult character reveals themselves to be just as self-absorbed as Lisa, if not more so. Consider a scene in which Matthew Broderick‘s English teacher is challenged by one of his students, and resorts to a childish “I’m right, you’re wrong” declaration. Or when Emily turns on Lisa, asking the young girl threateningly: “why do you care?” To Lisa, it’s obvious. But then, there’s always ulterior motives in these situations.

In Lonergan’s world, all years get you is more ways to excuse yourself and ignore the bigger problems. His ambitions are clear, his execution a bit less so. By the conclusion of this piece, Lisa exists as the only crusader of right in a universe full of wrong. Sure, it’s a bit much, but isn’t everything to a teenager?

Margaret hits limited theaters on September 30th.