Lincoln is a right up director Steven Spielberg‘s alley. This is both for good and ill. Spielberg pulls tight on the reins on the story of one of our most legendary presidents. The plot description would only carry a SPOILER WARNING for 7-year-olds. Abraham Lincoln’s story is an American fable: Honest Abe, the man who ran miles to return a penny, who slayed a forest and built a log cabin, who nobly fought the South to free the slaves. For a filmmaker who can make legends out of horses (War Horse), this is a cake walk. He just needs to bolster the Lincoln legend, and in that he succeeds brilliantly. How he goes about doing it, though, is the real question mark.

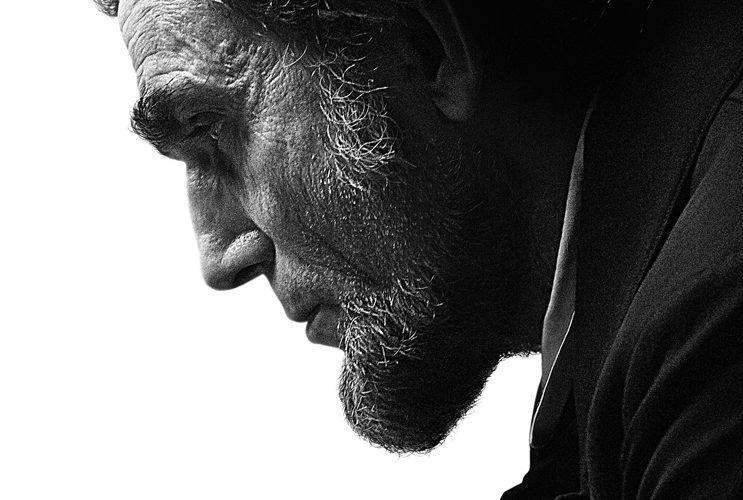

Take the opening: A stoic Lincoln sits under a makeshift canopy on some God-forsaken battleground near the end of the Civil War. Bathed in shadow with an almost angelic back light, the Commander-in-Chief listens to two of the multitudes of black Union fighters assembled in rank and file just behind. These slaves-cum-soldiers eloquently talk to the President with measured, controlled speech regarding a proper bounty for fighting: their freedom. As Lincoln mulls this over, two young, white fighters nervously skitter towards the platform. They treat meeting their leader, an excellent Daniel Day-Lewis, like teenagers flocking to [insert your age-appropriate pop act here]. The plebes were roused to action by Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, which the white soldiers fumble through when reciting the words back at their author. When the entire regiment is called back into action, one of the black soldiers lingers just long enough to finish the opening’s creed, eliciting a knowing nod from the president and a slight sigh from your reviewer.

The film is centered around another impeccable performance from Day-Lewis, who brings an affable charm and humanism to the tall lawyer from Illinois, carrying out some of the schlockier bits with dignity and grace. Lincoln deals with his wife Mary Todd (an often too shrill Sally Field), who has not gotten over the loss of their son, with great sympathy, especially as their eldest (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) bolts from Harvard in order to enlist. And you thought juggling the lives of the anonymous weighs heavily. The only time Lincoln is allowed to relax is with his youngest, Tad (Gulliver McGrath), who loves dressing up as a soldier and playing with photo plates of young black children. It explains why Lincoln’s shoulders slump on his wiry frame when that famous hat rests upon his weary head. And we haven’t even dealt with the country he rules that is currently torn asunder.

Lincoln is set with two ticking clocks: the imminent ending of the Civil War and the window for passing the Thirteenth Amendment, banning slavery in the United States. The film ably shows the back-room politicking necessary to achieve both goals before the President’s inauguration a month later. If they don’t pass this amendment before a Southern surrender, there is no way it will be ratified by one half of the country whose economy profits off the back of free labor.

Though Lincoln, a Republican, was recently re-elected to his seat, he is not beloved in the halls of Washington. Take the necessary House of Representatives, where Lincoln is slogged as a hateful dictator by Democrats, while his own party is split, finding him to soft for Abolitionist ideals or castigating him for discussing slavery while American blood is used as fertilizer up and down the east coast. When Lincoln concocts the plan to force this issue through with his Secretary of State William Seward (the always-sturdy David Strathairn), they find that the measure will come twenty votes short of ratification. Let the back room wonkery commence!

Lincoln must kowtow to the influence of Francis Preston Blair (Hal Holbrook) by agreeing to see an envoy of Confederate representatives (headed by Jackie Earle Haley‘s Alexander Stephens) to bring an end to the war. Seward is dispatched to blunt the ambitions of Thaddeus Stevens, the essential head of the hard-line Abolitionists. It’s a role Tommy Lee Jones was born to play, combining his stoic nature with a keen wit and great capacity for sentiment. Indeed, the main thrust of the emotional story of freeing the slaves is experienced through Stevens as Lincoln awaits the decision in the White House.

It will take a bit more than keen rhetoric to sway the Democrats, so a team of lobbyists/wonks/charmers are dispatched to get the votes. This arc – its own small heist film – features the professional work John Hawkes and Tim Blake Nelson with the foul-mouthed and, well, foul in general James Spader. They imbue the mainly somber and serious film with a bit of screwball madcap to great effect. Take note of the squirming nature of Walter Goggins‘ Wells A. Hitchens who is not above literally running away from his problems, or the subtle wavering in the face of Michael Stuhlbarg‘s George Yeaman. We obviously know the final result, but Spielberg and writer Tony Kushner keep the suspense loaded, riding a wave of emotion. I’m not above admitting that I teared up over several sections, shaking a rueful hand at the screen and muttering “Spielberg!” under my breath.

Lincoln, based partially off of Doris Kearns Goodwin‘s book “Team Of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln” makes me wonder how quickly Howard Zinn is spinning in his grave. But for all of the film’s mawkish inclinations, it’s still affecting. Too often does Lincoln spin yarns that eventually give an answer to whatever debate is temporarily frozen for him to finish, but I’ll be damned if I’m not on the edge of my seat for every one of them. The film looks fantastic, thanks to Spielberg regular Janusz Kaminski, even if he relies a bit too heavily on dramatic key lighting to drive the point home. John Williams, contributes another moving score, over-used to highlight almost every big speech (you can tell when the debating ends and the monologues begin when the strings start up).

Lincoln is earnest in its dramatic truth if lacking in its historical verisimilitude, but it is so well made that it’s hard to really find fault. This is a film built for awards season, and I’m sure it won’t go unrecognized.

Lincoln hits limited release in New York and Los Angeles on November 9th, and opens nationwide on November 16th.