At a certain point it becomes impossible to see a great artist as a person. Rarely do we think about Van Gogh as a toddler. Try to conceptualize Martin Scorsese as a ten-year-old, on the cusp of coming to grips with the impulse to create. And not just as a “once and future artist,” but as a living breathing human being existing in an ecosystem, a community. Citizen of a town or city, son to a mother and father, student in a school of people who, at the time, all see themselves on an equal footing, all equally as a ignorant to their futures, be it filled with success or larded with failure. No person comes into this world knowing they are made for greatness. For the first few months, even Beyonce had no idea who or what she was. Yet we are all shaped by our highs and lows, the instantaneous and the perpetual, all leading us to our future.

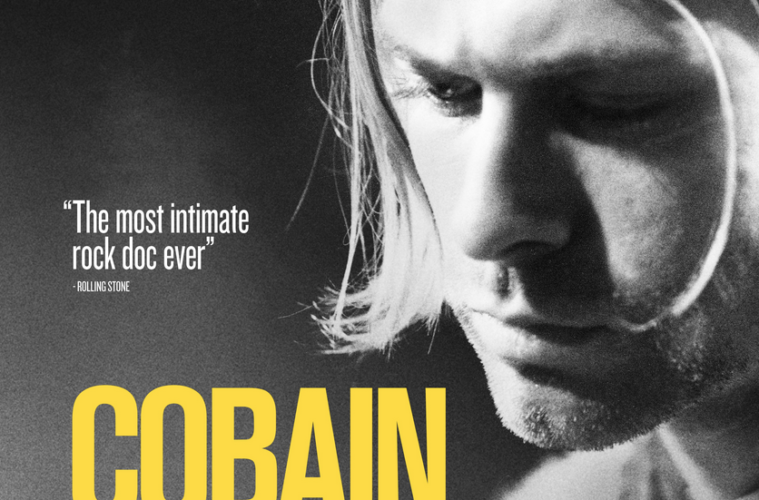

Still, it is easier to realize this intellectually than to have your entire image of someone retroactively amended to account for their humanity. It is the great triumph of Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck that it manages to rewire the way one thinks about Cobain through nothing more than the writing, illustrations, music, and videos of the man himself coupled with brief conversations with his family and friends. No doctors, no journalists, no art historians or music producers or critics – just the life remnants of the man who became the Voice of a Generation.

For personal context, which I usually shy from, I was only six years old when Cobain died by self-inflected gunshot. I don’t remember the day he died, and I can hardly remember the day I first heard Nirvana. Growing to love the music of Nirvana and learning about the myth of Cobain (his genius, his torment, his hatred of fame, his drug problem, his suicide) was like coming to an old religion. Yes, it is cliched and yes, it is almost hilarious to say out loud, but seminal bands and the moment of their discovery take on this kind of poetic resonance as one grows older. Kurt Cobain was not a god to me, don’t misread me, but he was a figure of supreme unreality who seemed to exists always in my mind in the fame-filled moments before his death, suspended in the amber of my own lack of knowledge and his popular cultural myth.

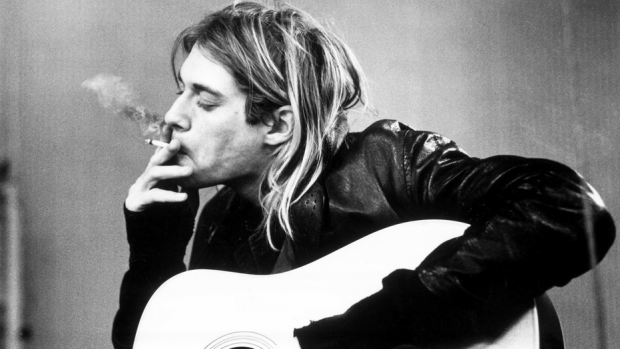

Writer/Director Brett Morgen tells the story of Cobain’s life chronologically, beginning with the grand mistake that was his parents’ marriage and following it through to his eventual death. Equal treatment is given to his childhood as to his time struggling in Nirvana’s nascent stages and on to their eventual stardom. As such, we as the audience are given the chance to grow to know Cobain at every stage of his life, cooing over him as a smiling baby and then watching his slow turn towards the bleakness and alienation and disaffection that would define him in the popular imagination. The blocks are laid one by one, pulling us along with the development of this human being, seeing his baby photos and home movies, reading his words in his hand on his pages. There is a power here, a humanizing element in the raw vulnerability of that childlike handwriting, those words sharp with passionate scrawl and yet mangled by unpracticed penmanship.

The documentary threatens to tip over into over-stylization with the certain digressions that occur a few times throughout the course of the two hour-plus run-time. In these vignettes we listen to records of Cobain as he records his thoughts and memories and we are treated to animations (possibly rotoscoped) which illustrate his words to us. Given the purity of the other images we see (even when those images are animations inspired by his illustrations) it is at first jarring to see these beautiful-yet-too-artful evocations of his life. Still, there is a kind of haunting, illusory quality to them that lets them pass into the narrative of the film seamlessly. To see these imagined moments with their fictional perfection of hue and tone juxtaposed with later home movies of Kurt and Courtney Love living together, hair stringy and bodies bruised and battered, creates a sort of tonal harmony. The further we get from that smiling child, the more we dip into creation myth before being ripped back into the well-documented finality of his life.

When the outcome of a certain story is known, especially in a case when it is as well publicized as this one, it can sometimes be hard to wring any new emotions from an audience. Yet Montage of Heck makes the tragic end of Cobain’s life more heartbreaking through it’s delicate retelling of his 27 years (a haunting number to consider, given that it is my own age at time of writing). It removes Cobain’s death from a public sphere and moves it into an intimate, personal arena. All the same, it still makes the loss sting even more on a personal level for the audience, because we finally see not just what we lost as a generation or a music listening public, but what he lost as well. Seeing Kurt Cobain at home with Frances, his infant daughter, and reading his panicked, raw words regarding his devotion to her, it makes our own reaction to his passing seem all the more strange and selfish, even as we empathize and ache more than ever. We lost an artist, but his daughter lost her father, and he lost not only her, but himself.

Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck is currently screening on HBO and available on HBO Go.