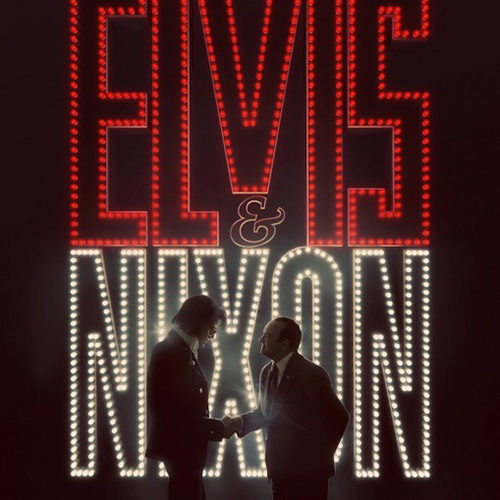

It is the most requested image in the National Archives, likely because of the tantalizing possibility and cheerful incongruity it summons. Elvis ‘The King’ Presley and Richard ‘Tricky Dick’ Nixon, two of the more confounding and eccentric figures of their respective time, standing there in the middle of the Oval Office shaking hands and looking mutually magnanimous. What had they discussed? How did these two men—singled out and scrutinized in differing ways by a public fascinated by them—approach one another? No official record of what went on during that meeting exists, but Liza Johnson’s enticing conjectural account of it is the centerpiece of Elvis & Nixon, a fascinatingly weird little movie that both teases and satisfies our pop curiosity.

The strength of Elvis & Nixon is rooted in a playful imagination that strives to work plausibly within the confines of what we know about these two men while also having some fun with the inherently bizarre nature of their meeting. Working from a screenplay by Joey and Hanala Sagal and Cary Elwes, Johnson combines quirky wish fulfillment with enough off-the-wall but legitimately true historical details to offer us a version of events that come off as potentially genuine, whether or not they are. One of these is why Elvis had come to visit Nixon on that day in December, 1970; after watching Dr. Strangelove, the King was convinced he’d make a great federal agent waging a war on America’s drug problem. Nixon, presumably looking to capitalize on a one-of-a-kind photo op, gives an audience to Presley’s odd request.

Michael Shannon and Kevin Spacey don’t much physically resemble either Elvis or Nixon respectively, but in many ways this makes the film more intriguing. Instead of historical pantomime, we get something closer to impressionistic extrapolation, with the performers burrowing down deep to find the connective tissue that unites these towering enigmas. Both actors deny their formidable and recognizable personas, effortlessly shrugging off expectations and delivering surprises; Shannon’s breathy, almost ephemeral take on latter-day Elvis is potentially farther out of his wheelhouse than Spacey’s paranoid, isolated Nixon. Together, they keep the film’s slight stature from blowing away in a gusty, speculative breeze.

Of the two, Shannon’s performance is possibly the more intriguing, although this doesn’t lessen the sturdy, gruff wall of insecurities that Spacey summons when channeling Nixon. Waging a mental war against alleged opponents and public opinion, Spacey’s Nixon is already well weary when his advisor s (Colin Hanks and Evan Peters) suggest he meet with Elvis, promising an opportunity to connect with the mainstream public and even impress his young daughters. Spacey gets the square, jowly grumpiness and cautious posturing of Nixon down perfectly, but what he really brings to the table is a compelling sympathy for the man’s insecurities and frailties, captured best in almost throwaway moments and gestures. Watch the way he responds when Elvis decides, against the advisement of White House aides, to treat himself to the President’s restricted bowl of M&Ms and lone bottle of Dr. Pepper. This external bonding over junk food sets the stage for a near existential kinship, one what wouldn’t be evoked without the chemistry between Spacey and Shannon.

Coming off the peculiar but pleasing Midnight Special, Shannon proves here that his talents as an actor can’t be easily pigeon-holed or predicted. His Elvis is one of the most unlikely portraits we’ve seen, but it may also be the most significant in terms of getting down to seeing the man beneath the glitter and the glam and late-stage kookiness. If we’re ranking things, he’s right up there with Kurt Russell’s lively, passionate rockabilly in John Carpenter’s Elvis and Bruce Campbell’s ornery, exhausted geriatric in Bubba Ho-Tep. So often a performance of this type rests upon physical tics and vocal intonations, particularly when the bulk of the movie relies on dialogue in a scenario that plays like a small-screen two-hander. Shannon doesn’t approach Presley from the outside and work in, but the other way around. This Elvis has become something of a lost soul, and even his sojourn to D.C., with the younger likes of Jerry Schilling (Alex Pettyfer) in tow, feels like a desperate effort to re-establish a personal sense of purpose. Elvis the performer and Nixon the president take an afternoon off to engage each other as men and somewhere in-between acknowledge a mutual loneliness brought on by their very public identities.

At 86 minutes, Johnson keeps the movie slender and lean, which is probably the right approach. Nothing in Elvis & Nixon feels particularly integral or essential, and so the whole endeavor blows in and back out without much dramatic impact. This isn’t really a criticism at all, but an observation, and in some ways, a compliment. Johnson structures the movie early on as if it’s the out-dated kooky B-movie version of itself and even when the two heavyweights get down to it, she refuses to frame the film in lofty terms. The visual texture is lively without being scattershot; character placement within the frame is more important to the narrative than any particular shooting method. We are left yearning for something a bit more substantive, scouring what’s there for a connection that will prove lasting, but in this way the filmmakers have ultimately squeezed us into the shoes of these two men, feeling more than seeing what might have happened that day in December. Maybe it didn’t go down this way, but when you’re done here, you’ll feel that maybe it should have.

Elvis & Nixon is now playing in wide release.