There is inherently a great risk that filmmakers face while crafting a drama about “great men.” Whether they are artists or politicians, innovators or explorers, there is an oft-irresistible urge to valorize the legend of the person and their accomplishments, rather than delve into their passions, motivations, and weaknesses. Danièle Thompson, director and writer of Cézanne et moi, certainly seems to invite these difficulties by telling the story of not one, but two great men.

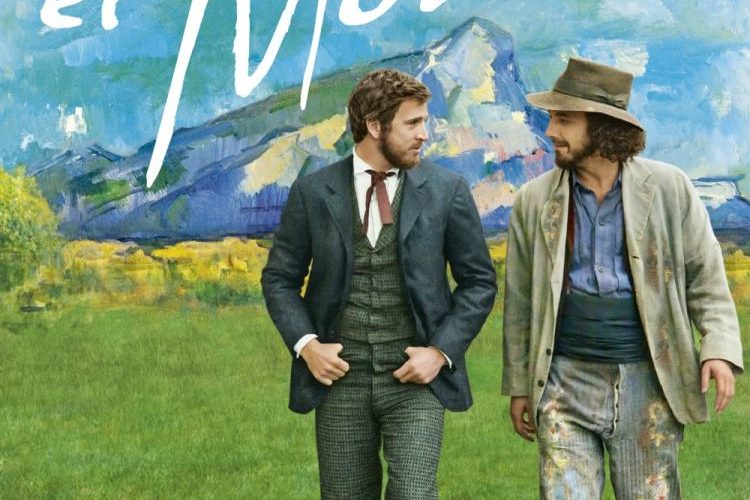

Cézanne et moi explores the mercurial friendship of Paul Cézanne (Guillaume Gallienne), the legendary Post-Impressionist painter who heavily influenced some of the greatest 20th century artists like Picasso and Matisse, and Émile Zola (Guillaume Canet), the eponymous “I” and a highly respected novelist and poet of naturalism and political advocate. In grounding the movie in this very real and human relationship — and forgoing many of the more galling and hackneyed “struggles of the artist” conventions — Thompson avoids easy comparisons to, say, a Wikipedia page about her subjects. Unfortunately, Cézanne et moi only occasionally succeeds in marrying the time-jumping narrative to a concrete sense of emotion. Ironically, it succumbs to the clichés of the coming-of-age genre and standard cinematic depictions of male friendship than it does the biopic.

The viewer is first introduced to Cézanne and Zola in middle age, as the two meet at the latter’s country house. Cézanne et moi jumps between this encounter and a fairly linear retelling of their friendship spanning from their first meeting to well past the “present” rendezvous. This is, in some ways, one of the film’s primary faults: the artists frequently make references to events and people in the present that are only clarified in the flashbacks that take place later, and the crucial reason for their current tête-à-tête is only revealed to be of significance close to the climax. Instead of fostering a sense of mystery about these historical figures as was presumably intended, this frustrates, clashing with the often raw emotions that ensue in both past and present.

Zola and Cézanne are cast throughout the film as foils. The former is in essence the viewer’s point of view looking at the nascent master that is Cézanne; he is by and large reserved, only expressing equivalent emotion as his compatriot on a few admittedly well-chosen occasions. Cézanne, on the other hand, is depicted as something of a firebrand, belonging to the wave of young turks (including Édouard Manet) that made a splash when they displayed their paintings rejected from the Paris Salon in the now legendary 1863 Salon des Refusés. He is moody and impatient, prone to destroying canvases he is unsatisfied with and chastising his paintings’ subjects for not remaining still “like apples.” Additionally, he is insecure and frequently accused by many of his friends and acquaintances (including his estranged wife Hortense and Zola) as being cold and heartless.

Still, there is very clearly a genuine (if not unshakeable) friendship that develops between the two creative. Early on, before much of the turbulence, they are called “the inseparables,” and while this designation isn’t strictly true – Cézanne frequently retires to his bourgeois parents’ home in Aix while the poorer Zola stays with his widowed mother in Paris – the two interact with no small amount of playfulness and warmth. Thompson depicts this relationship and its dissolution with perhaps too much determinism without delving much deeper than surface appearances, even if there is an easy pleasure in seeing their interactions.

Where Cézanne et moi genuinely runs into trouble is its depiction of artistry. Thompson entirely eschews signposting through the presentation of the extremely famous works of either artist, but there is very little art in place of those. This is not referring to the actual filmmaking craft, notable only in the sometimes alarmingly frenetic editing in some of the earlier passages, but to the craft of the protagonists. Cézanne’s work is represented mostly in brief glimpses glanced during scenes of him painting, almost always on canvases that end up mutilated, and Zola’s writing is almost entirely absent. True, it is more pleasing to show shots of a paintbrush daubing a palette than a pen scrawling on a page, but there is an uneasy sense that Cézanne is the sole true subject the film is interested in, with Zola serving merely as observer.

It should be reiterated to Cézanne et moi’s benefit that neither man is glorified. Cézanne essentially switches class positions in life with his friend, as he lives in a reclusive hovel while Zola resides in a lavish country household, and both toil away to little real recognition (at least, during their lifetimes). Even more commendably, the film ends on a remarkably downbeat and melancholy moment only slightly cheapened by the seemingly requisite closing intertitles describing the legacy of the subject (which, again, almost entirely features Cézanne). Cézanne et moi alternates between frustrating and engaging, but there is no doubt that its soberness in the face of luxury and genius, and its fidelity, despite some slight shallowness, linger on.

Cézanne et moi opens in limited release on March 31.