The dedication at the end of The Plastic House is short and sweet: “For Mum & Dad.” Like the rest of writer-director Allison Chhorn’s documentary, that dedication is presented in subtle, quiet fashion. The Plastic House is a largely quiet film, one drenched in emotion but never outwardly melodramatic. Often dialogue-free, plotless, and running just 46 minutes, Plastic is a uniquely involving sensory experience.

Despite the absence of any real “plot” and its reliance on visuals over dialogue, watching The Plastic House is not highly demanding. Unlike fellow NYFF58 entries—Tsai Ming-liang’s breathtakingly slow, wondrously moving Days, or even Frederick Wiseman’s four-hour-plus City Hall—Plastic is not a rigorous viewing experience. Rather, it is a film that moves briskly, at times even effortlessly, between nostalgic memory and a new reality.

Chhorn is an immensely talented Australian filmmaker, as adept at sound design and cinematography as she is at writing. As The Plastic House begins, we are presented with two pieces of somber on-screen text: “Mum, 1959 – 2015” and “Dad, 1959 – 2016.” Much of what follows is set in a large greenhouse, which, we interpret, was owned and tended to by Chhorn’s late parents. It is a fascinating space, and while we gain little sense of the geography that surrounds it, we do familiarize ourselves with the interior.

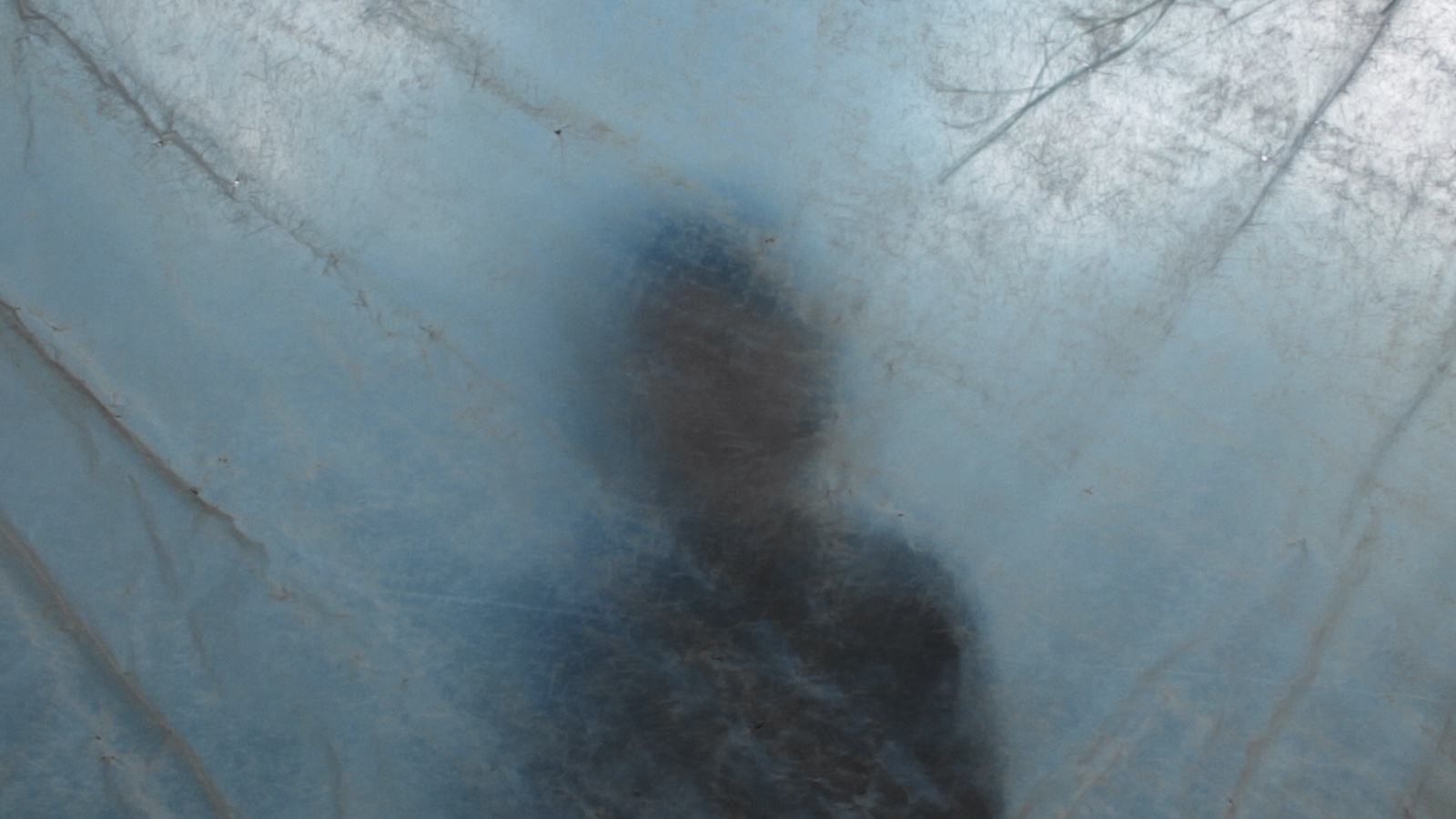

At a few points we suddenly hear dialogue, and the limited use of such sounds gives each word great significance. “If you can do a little work, it’s good for you,” says a voice which we assume to be that of Chhorn’s mother. “It’s good for your well-being.” Video footage of work being conducted in the greenhouse does seem good for one’s well-being. Yet Chhorn’s work in the greenhouse is done solo, and a sense of absence is palpable. This is a running motif in The Plastic House; nearly every shot in the film seems to accentuate absence and loss. A scene of Chhorn in a car, with just a bit of her face visible in silhouette, is a strong example.

Near the film’s conclusion, a lengthy passage from Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying appears on-screen in a book, with the following lines underlined: “In a strange room you must empty yourself for sleep. And before you are emptied for sleep, what are you. And when you are emptied for sleep, you are not. And when you are filled with sleep, you never were. I don’t know where I am.” The words connect powerfully with Chhorn’s themes of shakily entering an unknown world. What, Chhorn seems to be asking, is the greenhouse without her parents? Where does she fit? Chhorn walks into dense fog, alone, as The Plastic House winds down, before cutting to video of her parents at work together. It’s a memorable metaphor for the end of childhood, an intelligent decision befitting the project at large.

The Plastic House screens at the 58th New York Film Festival from October 6 through 11.