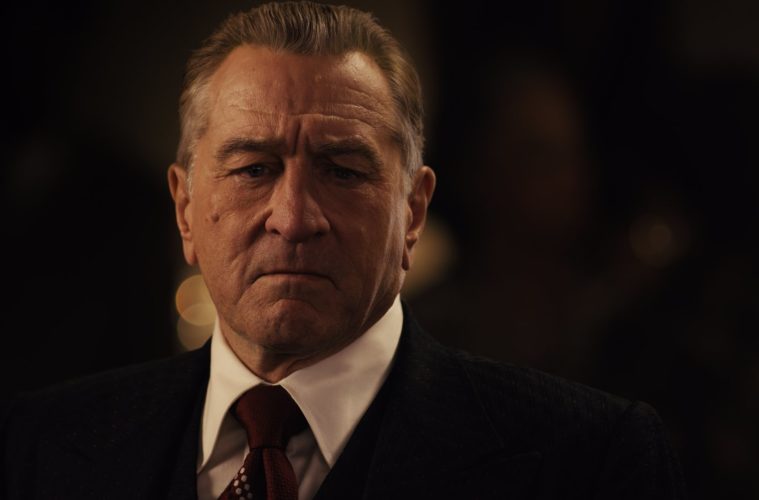

It’s a critical cliché to describe a filmmaker’s late-period output as elegiac, nostalgic, or any other adjective that suggests an aging artist grappling with their own mortality. With that said, Martin Scorsese actively courts this framework for his latest film The Irishman, a 209-minute crime epic that reunites him with actors Robert De Niro and Joe Pesci, with whom he hasn’t worked since Casino in 1995. All three men, along with co-star Al Pacino, are septuagenarians who have been working in the film industry for upwards of half a century. To watch The Irishman means to confront their age, history, and inevitable decline. Scorsese filters this idea through a dramatization of a mob enforcer’s life, but there’s no ignoring the self-reflexive mode on display.

Spanning 40 years of history and told through two separate framing devices, The Irishman chronicles the rise of Frank Sheeran (De Niro) in the ranks of the Philadelphia mafia as well as his close professional/personal relationship with Jimmy Hoffa (Pacino). After falling into the good graces of mafia boss Russell Bufalino (Pesci), he’s asked to play the middleman role between the Mafioso’s and the Teamster union. But as Hoffa’s relationship with the union and the mafia wanes, Sheeran becomes irrevocably trapped between the two factions.

That bare summary obviously doesn’t include an enormous ensemble cast and the myriad subplots that comprise this dense film, but anyone even casually familiar with Scorsese’s gangster films, or mafia films in general, can put together the pieces in their heads. Money is stolen, hits are taken out, and people are intimidated against the backdrop of 20th-century American history (roughly post-WWII through the Gulf War). The Teamster heads and the mafia bosses sport familiarly prideful, petty personalities; they’re more concerned with decorum and tradition than rational pragmatism, and will likely resort to violence if their image has been denigrated. If problems can be solved quicker with the sword than the pen, the sword will be used. The only meaningful difference between the union politicking in The Irishman and Frank Costello’s gangster exploits in The Departed is the respectable optics of the former.

For two-thirds of its runtime, The Irishman resembles a Scorsese greatest-hits compilation, minus the signature ’60s and ’70s pop/rock soundtrack (“Gimme Shelter” is nowhere to be found). However, Scorsese’s use of de-aging effects technology throws the main action in a more melancholic register. The in-the-moment success of the VFX will depend on personal mileage (I personally found them to be mostly seamless), but the audience nevertheless has to wrestle with the gap between the characters’ youthful visage and the curbed movements of elderly men. When De Niro’s character beats up a grocery store owner for shoving his young daughter, it’s not accomplished with the verve and tenacity of a man in his late 20s, the age when the actor played Mean Streets’ Johnny Boy, but with the precise, circumscribed care of a guy getting up in his years. It’s still effective within the film’s diegesis, but Scorsese employs a distancing effect by foregrounding the age of his actors. Whenever you’re watching The Irishman’s three stars, you’re constantly made aware of the relationship between their work in the film and similar works made as younger actors.

It’s almost impossible to discuss The Irishman without at least mentioning Goodfellas because the films are in direct conversation with each other. While the nastiness of Goodfellas lies in the gap between the glamorous ends and the brutal means, The Irishman skips the lifestyle allure almost completely, focusing exclusively on Sheeran’s walking-on-eggshells routine and coded conversations, occasionally punctuated by callous, unsexy violence. Scorsese abides by a similar rise-and-fall arc, complete with “good times” curdling to bad and stinging betrayals, but the mirth has been drained out of it. He even reframes at least two famous scenes from the film in a downright despairing, sorrowful light, as if the 76-year-old auteur wants to prod his own career in the ribs just a little bit.

That’s not to say that The Irishman isn’t eminently enjoyable and often fleet for its entire 209-minute runtime. Scorsese and editor Thelma Schoonmaker keep the action remarkably fluid, with scenes playing out as briskly or as leisurely as necessary, never once coasting on either the actors’ charisma or the expensive production design. (With over 300 scenes and over 100 location shoots, not to mention the cost of the digital effects, Scorsese took Netflix for every dollar he could.) It’s also very funny in a modest, unshowy way, with the humor relegated to line deliveries and amusing digressions that only a film of such scope could accomplish. It’s fundamentally not worth making The Irishman shorter if it means losing, say, a hilarious conversation about fish, or an anecdote about filling a watermelon with vodka, or a voiceover explanation of why frying corndogs in beer makes them taste better.

Not that The Irishman’s scale and length needs any explicit justification, but the film’s final hour, which chronicles Sheeran and company’s slow crawl to the grave, gives the game away. It’s rare to watch the mundane unpleasantness of aging on film at all, but it’s even rarer to see it communicated in such woeful terms. It’s here where The Irishman accumulates its emotional heft, as we watch a colorful life become reduced to broken relationships, a rapidly degenerating body, and desperately insincere pleas to God for salvation. There’s a real enervating anxiety of being completely forgotten that retroactively colors the rest of the film in stark, unsparing terms. The Irishman’s ending illustrates that even the toughest men, or the most celebrated filmmakers, still crave a sliver of light to guide them through the encroaching darkness.

The Irishman premiered at NYFF and opens in limited release on November 1 and will be available to stream on Netflix on November 27.