French-Algerian visual artist and filmmaker Neïl Beloufa’s second feature, Occidental, opens in media res as its eponymous setting, the tawdry Hotel Occidental, is going up in flames. Its exterior is beset by clashing police and protesters while a man is vexedly trapped inside one of the inn’s rooms, seemingly more annoyed than distraught despite his presently dire situation. This familiar setup suggests that, by the time the film catches up with this scene, the chain of events that preceded it will have provided some clarity or context for the sequence and lead to a fuller understanding of how and why things wound up this way. But as the subsequent opening credits, set against images of the lethargic, largely anonymous protest that led to the ensuing riots, imply with their dual-layered text (tinted by retro pastels scattered haphazardly around the frame), this will not be the case. Beloufa aims to play with audience expectations by obfuscating traditional narrative continuity and presenting a politically ambiguous narratological experiment. Yet these gracelessly executed efforts appear fundamentally frivolous in the end.

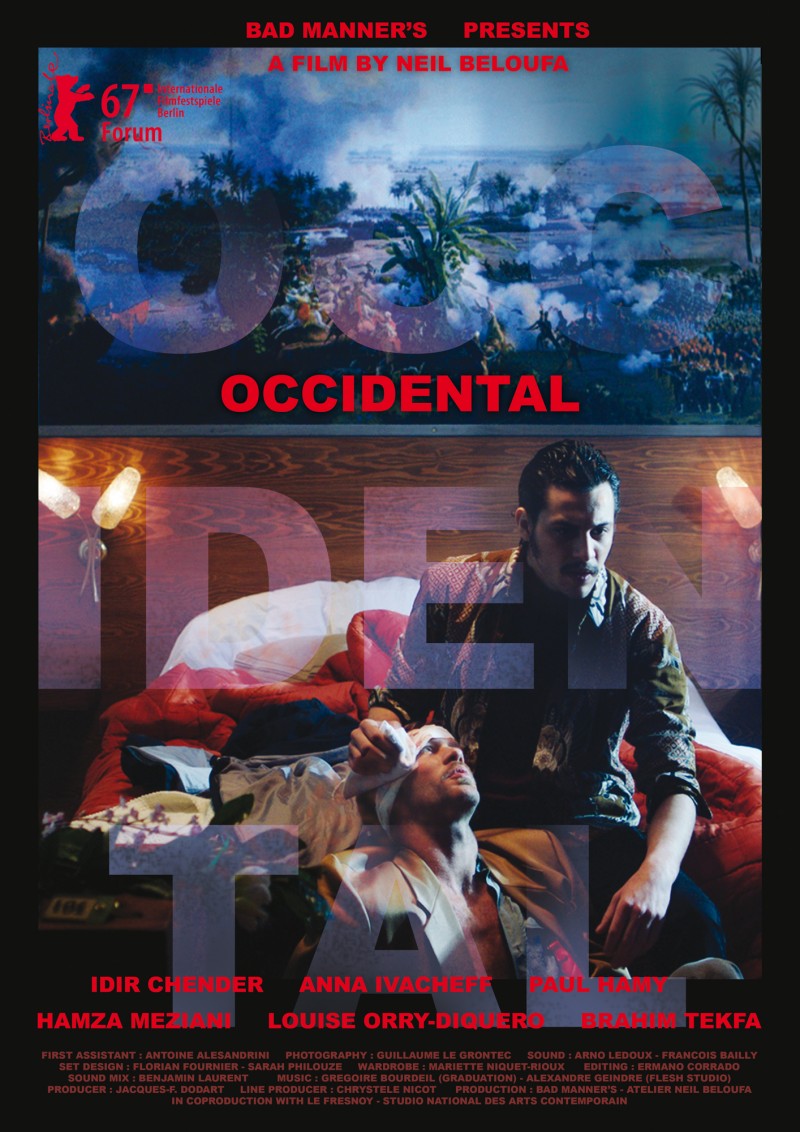

Two Italians walk into a ‘70s pastiche hotel, each sporting similarly retro apparel, one — the sly conversationalist, Giorgio “Armani” (Paul Hamy), wearing an oversized yellow fur coat — while the other, Antonio (Idir Chender), an unpredictable provocateur, dons a vintage tracksuit. This premise might seem like some kind of silly joke and, in many ways, it is, as the appearance of these dubious Italians — their accents as slippery as their intentions for lodging in the Occidental’s honeymoon suite — gradually send the hotel and its quirky staff careening towards inane, malapropism-filled absurdity and, ultimately, total destruction. Immediately suspicious of the duo and peculiarly au fait with Antonio, manager Diana (Anna Ivacheff) starts to play hotel detective, diligently keeping tabs on them with the assistance of doting desk clerk who also serves as the film’s tacked-on unreliable narrator, Romy (Louise Orry-Diquéro), and fainting-prone bellhop, Khaled (Hamza Meziani, best known for his scene-stealing role in this year’s Nocturama). Throughout the night, the staff will have to contend with these mysterious men, a coterie of oafish limeys attending their perpetually sloshed mate’s stag party, as well as the increasing danger of operating business in the middle of a hot zone. Each character perspective highlights the perceptual malleability of objective reality as conjecture, paranoia, and the unknowable threaten to pierce the generally desired anonymity provided by temporary lodging. However, these threads go nowhere as Beloufa’s own shallow artifice interferes with these ideas fully connecting.

Even with its lush sets, designed with modern elegance in the vein of retro styles, Occidental is resoundingly dull, visually and dramatically. Beloufa’s eye for florid mise-en-scène is indeed distinctive, but his bumptious camera movements — long takes that track choice characters through the elaborate hotel set as they perform actions as if they’re in a Tati-esque playhouse — often ring hollow for lacking finesse, underscored by a trite ‘70s-retro electronic score that practically begs you to invest in the banality. There’s an overriding sense of inconsequentiality to the proceedings, in large part due to the shambolic performances. Blocked in a sideways lineup, relatively front-facing save for those aforementioned moments of formal fancy, the actors are exasperatingly rigid, automated according to their mystery-story archetype, and following their trajectory as the tactless script ordains — an affect that could resemble the abstract social puzzles of, say, Resnais, but is in effect more like an episode of Scooby-Doo sans any campy charm.

Save Hamza Meziani, the cast of Occidental seem alienated from their roles or in their politically vague cyphers, arbitrarily designated by Beloufa in his sophomoric satire that’s full of dead air and lacks any real bite, let alone proper comedic timing. These characters slip in and out of parody (e.g. Romy being a fawning ingénue that toes the line of intentionality as a regressive stereotype), but they’re so bereft of genuine distinction or humor that they hardly leave an impression. We eventually find, after a kitchen explosion that sets the hotel aflame and forces everyone to evacuate, that Diana and Antonio were once married, or perhaps not — their relationship is as unclear as what cause the protestors outside are fighting for, why the state is brutally opposed to said cause, or why any of this wild-goose chase in a hotel matters, anyway. Had Occidental expanded upon its ideas of perceptual and political objectivity — developing them beyond mere seeds — there would, at the very least, be a raison d’etre in the first place.

Occidental screened at the 2017 New York Film Festival.