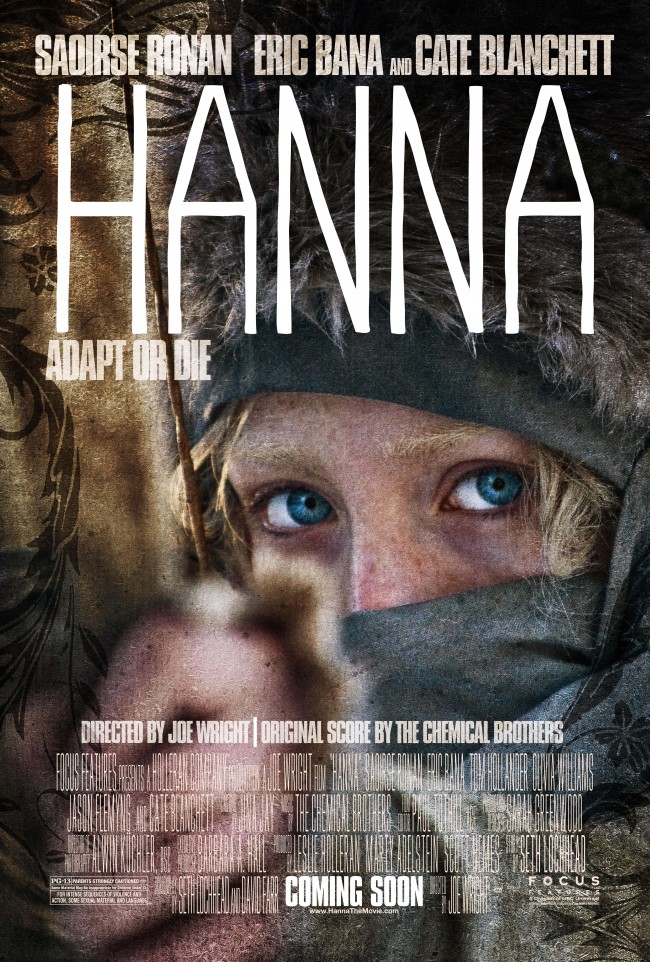

I had the pleasure of seeing Joe Wright’s fourth feature tonight, the action/drama/thriller Hanna starring Saoirse Ronan, Cate Blanchett, and Eric Bana. While I’m embargoed from sharing any thoughts, Focus Features shared a new clip and a variety of images from the film. The clip features some of the fantastic The Chemical Brothers score, and a snippet from one of my favorite scenes in the film. Check them out below, followed by production notes from the film. Click for hi-resolution versions.

Synopsis

A teenage girl goes out into the world for the first time – and has to battle for her life. Director Joe Wright weaves elements of dark fairy tales into the adventure thriller Hanna, filmed on location in Europe and Morocco.

Hanna (played by Academy Award nominee Saoirse Ronan of Atonement, also directed by Joe Wright) is 16 years old. She is bright, inquisitive, and a devoted daughter. Uniquely, she has the strength, the stamina, and the smarts of a solider; these come from being raised by her widowed father Erik (Eric Bana), an ex-CIA man, in the wilds of North Finland. Erik has taught Hanna to hunt, put her through extreme self-defense workouts, and home-schooled her with only an encyclopedia and a book of fairy tales. Hanna has been living a life unlike any other teenager; her upbringing and training have been one and the same, all geared to making her the perfect assassin. But out in the world there is unfinished business for Hanna’s family, and it is with a combination of pride and apprehension that Erik realizes his daughter can no longer be held back.

This turning point in Hanna’s adolescence is a sharp one; she is separated from Erik and embarks on the mission that she was always destined for. Before she and her father can reunite as planned in Berlin, Hanna is captured by agents dispatched by ruthless intelligence operative Marissa Wiegler (Academy Award winner Cate Blanchett). Marissa, a career agent, has long been harboring secrets that tie her to Hanna and Erik.

Detained for observation and held beneath the Moroccan desert, Hanna soon turns the tables on her captors. Her daring escape to above-ground thrusts her into an unfamiliar landscape and world which she must quickly learn to comprehend and navigate. Marissa secretly sends a team of agents after Hanna, and joins the deadly pursuit herself. As Hanna journeys across Europe and nears her ultimate target, she faces startling revelations about her existence and unexpected questions about her humanity.

A Focus Features presentation of a Holleran Company production. A Sechzehnte Babelsberg Film GmbH/Neunte Babelsberg Film GmbH co-production. A Joe Wright Film. Hanna. Saoirse Ronan, Eric Bana, Tom Hollander, Olivia Williams, Jason Flemyng, and Cate Blanchett. Casting by Jina Jay. Costume Designer, Lucie Bates. Associate Producer, Josephine Davies. Co-Producers, Carl Woebcken, Christoph Fisser, Henning Molfenter. Music by The Chemical Brothers. Film Editor, Paul Tothill, ACE. Production Designer, Sarah Greenwood. Director of Photography, Alwin Küchler, BSC. Executive Producer, Barbara A. Hall. Produced by Leslie Holleran, Marty Adelstein, Scott Nemes. Story by Seth Lochhead. Screenplay by Seth Lochhead and David Farr. Directed by Joe Wright. A Focus Features Release.

About the Production

Not yet out of her teenage years, Saoirse Ronan is already an Academy Award nominee whose performances continue to impress. But when asked what method she utilizes to get into character, the actress replies, “I don’t know whether I have one. I’m not the type of actor who lives through the character.”

Even so, as she explains, “I want all the roles that I play to hold challenges. With lots of action and a layered character, Hanna had them for me. It’s unlike any other drama that I’ve done. Here is a teenager who has been raised in a forest and has gotten all her education from her father; she’s never even met anyone else before. We meet her as she goes out on her own, and when she does she is fascinated by everyone and everything she comes across. My favorite quality of hers is that she is non-judgmental; she shows an open mind to, and a fascination with, everything. She’s a bit of a freak. But, I like that; I like freaks.

“Hanna discovers life for the first time, so the movie is not just about a girl who kicks butt – though she certainly does!”

Ronan embraced the concept. She remarks, “[Director] Joe Wright talked with me about how – as in a fairy tale – someone goes out into the world and it is overwhelming and scary and beautiful. Like any teenager, I can empathize with Hanna’s desire to see the world, but for her it happens at 100 miles an hour.”

The actress – who would turn 16 during filming of Hanna – had boarded the project even before her once and future director, Wright. It was he who had cast Ronan in Atonement nearly four years prior, with their resulting collaboration earning awards and accolades all over the world.

She reflects, “I always thought that if we were going to work together again, it would have to be something different from what we did before.

“Joe and I didn’t need to find our way; we are very in sync, even more so than before because we can tell if either of us is not completely happy, and we trust each other to try different things. Both Joe and I sympathize with Hanna because she does what she does to protect the people she loves.”

Seth Lochhead had written the original screenplay for Hanna in 2006. The script then continued on through development. Academy Award-nominated producer Leslie Holleran, who has successfully brought to the screen a number of literary adaptations, remarks that “it’s extremely freeing – and even more terrifying! – to work on an original story. Hanna goes on a journey, and developing the script for a couple of years was a journey in its own right.

“With Hanna, Seth had written a character of mythic quality. She is a stranger in a strange land – namely, our world. I was intrigued by the human connections she would make.”

Holleran adds, “I wanted to find a director for whom this movie would be a departure. Joe’s strong take was exploring the story through the prism of a fairy tale. What was also exciting was his thinking in terms of the action, the character elements, and even social commentary; this is a female empowerment story.

“I believe that his deep familiarity with Saoirse and what she is capable of as an actor gave him a confidence to be ambitious with the material.”

Once Wright was confirmed as the film’s director, Lochhead reports, “Joe invited me back to work on many scenes – ones that had been in the script since 2006, as well as ones that had come into it in the years since.

“I felt like Joe understood what I was trying to do, and I could see where he was coming from, with the story. We saw the characters the same way, so it was very exciting to go back into Hanna’s world.”

At the start of the film, the only person Hanna has in her world is Erik, her widowed father. Actor Eric Bana remembers, “The script reminded me of…nothing; I thought, ‘I haven’t seen this film before.’ I loved that this movie has a teenaged girl as the main character; what an exciting opportunity for Saoirse at this age. Joe’s take on the story fascinated me, so I quickly jumped on board.

“Hanna has to grow up and take on responsibilities, as her parent relinquishes control. I’m a parent myself, and I saw Hanna as a heightened version of every parent’s nightmare of their child going off for the first time.”

Bana was also drawn to his character’s complexities. He notes, “There are very traditional fatherly qualities to Erik; he’s a protector and a teacher. He’s forever been preparing Hanna to survive battles both mental and physical, so he’s also like a cruel drill sergeant with her.

“Yet, when a parent has done a great job of protecting their child from the world, the harsh realities out there are that much more shocking for the child, and Hanna is in real danger.”

The threat to Hanna is incarnated by Academy Award winner Cate Blanchett; she portrays the film’s third major character of Marissa Wiegler, the cold-steel magnolia CIA agent who once upon a time worked in the field with Erik. Now based in Langley, VA, Wiegler’s life has been “built around the telling of lies and the holding of secrets, and she has given her all to her job,” notes the actress.

As part of researching the role, Blanchett spoke with a CIA agent who illuminated for her “the tension that exists between those in the field and those who are at headquarters, in Langley.”

She elaborates, “Marissa worked undercover in Germany in the 1990s, and relished the cut-and-thrust of covert operations. The one she was involved with Erik in failed and was closed down, so she harbors incredible resentment towards the agency about the whole thing as well as self-loathing. When Erik and Hanna reappear, she goes back into the field to close them down. Finding Hanna starts out as a professional necessity, but becomes pathological, for her. She wants to possess this child; it’s a bit like the Wicked Witch from the Hansel and Gretel story. The fairy tale elements add a heightened quality to the scenes.”

Like Ronan, Blanchett had a previous professional tie to Wright. She reveals, “Joe and I were preparing another project together, and that fell through. Then he sent me this script, which terrified me; my partner noted that I’d never had a reaction like that to a screenplay.

“So Joe and I got to work; it was important to him that Marissa be from Texas, and I tried to get the accent subtly so that it wasn’t overpowering.”

Already at work was Wright’s longtime production designer, three-time Academy Award nominee Sarah Greenwood. The director’s frequent collaborator discussed adding “a fairy tale element through design, costume, and performances, and bring that quality to the fore.

“Lots of fairy tales originated as stories of warnings to children. As soon as Hanna steps into the world that Marissa inhabits, she learns fast lessons.”

Costume designer Lucie Bates adds, “Sometimes the dark fairy tale aspect was to be almost subliminal; Joe’s vision of Marissa as the Wicked Witch of the story meant that her colors would be red and green. Sometimes it was to be more open, as with Hanna and Erik’s cabin.”

Greenwood’s team, which per usual included set decorator Katie Spencer, worked with local craftsmen and “really built our characters’ log cabin out in the woods to look like it had been there for years,” marvels Bana.

The production designer reports, “Snow was the starting point in our design. The story begins, and the audience arrives in a place, and you don’t know where it is, what century it is, or who the characters are. Hans Christian Andersen was our inspiration, but we expanded on tradition to introduce our interpretations – including the book that Hanna has had at home.”

Blanchett adds, “Joe’s introducing a fairy tale aesthetic into the film draws on his own background in puppet theatre.

“As a director, he creates a safe environment where you can make a few mistakes, and then hopefully you make better decisions. Joe’s attention to detail is such that one minute he would be fixing my hem, the next helping to paint a set, and the next calling for the lens numbers. He is involved in every aspect of filmmaking.”

On Hanna, there was a new aspect for Wright to explore; putting the actors through a detailed regimen for rigorous action scenes. This provided an ideal opportunity to bond the actors playing father and daughter. Bana recalls, “Saoirse and I did some of our training together, and she was well-prepared, with great coordination. She was better than some of the men I’ve worked with over the years. It’s often harder to fight with an actor than a stunt person, but Saoirse was committed and engaged. Our fight scenes were unique, with a father teaching a daughter and not just two people going after each other and one winning.

“Turns out that her arm’s length reach is very long, and almost the same as mine. I had to be careful in our fight-training scenes together because those fists come at a great rate and with real force. I had to be very cautious not to hurt her – and not get knocked out by her. I’ve worked with a lot of guys who are not as tough as Saoirse is.”

“I know I hurt Eric a few times,” admits Ronan. “But Joe did tell me to go for it.”

“Saoirse and I also had a good time ripping into each other because, she being Irish and me being Australian, we were kind of kindred spirits in our senses of humor; hers is wicked,” reveals Bana.

Bana had experience in the physical arena from his other movies, but on Hanna stunt coordinator and fight choreographer Jeff Imada (fight stunt coordinator on both The Bourne Ultimatum and The Bourne Supremacy) had to “teach Eric some things to fit his character – and Hanna’s, since the father is training the daughter.”

Bana points out, “This was a little different for me because of the hand-to-hand combat – which I actually hadn’t done a lot of in earlier movies. There are physically demanding scenes between Hanna and Erik that have emotional punch as well.”

Given that Hanna is someone who has been in training for as long as she can remember, Imada began work with Ronan well ahead of production, while the actress was still publicizing her film The Lovely Bones in Los Angeles. He reports, “I put her through a few tests to get a feel for her body mechanics, and to ascertain how much work we needed to do to make her look convincing as a teenager trained to a high level of skill by her father, who himself was trained by a government agency.”

Wright wanted the fight scenes to look as naturalistic as possible. Given the setting that was being established for Hanna’s upbringing, Imada introduced an element of the wild into the fighting style. He explains, “Hanna is surrounded by wildlife; she has learned a keen awareness from animals, how to survive and how to fit into and live in the landscape.”

“When she kills, to her it’s like killing in the wild, from her upbringing,” offers Ronan.

Imada comments, “Saoirse has a slight build, so she could be agile, moving quickly and with stealth. I incorporated martial-arts kicks, aerobic exercises, and basic boxing and grappling moves into our training. We adjusted Saoirse’s diet to help build muscle. We also worked with weapons, using sticks so that they would become extensions of her arm.”

The idea was to “mold all this into her, so that when it came to the fight scenes Saoirse would be able to summon all of this, immediately convincing the audience – and that she wouldn’t tire easily!”

Life began to imitate art; Imada trained with Ronan for six weeks, with the teenager working “five, six hours a day – and she never complained,” he notes. “I sometimes had to tell her when to quit. She was determined to come across as Hanna. I was really impressed with her.”

Ronan proudly notes that she ended up doing “quite a few of the stunts myself,” yet admits that the first days of training were punishing; “Joe warned me, but I thought, ‘I’ll be fine, I swim and run [regularly].’ I’ve always been quite athletic.

“Well, there was a lot more involved than I thought there would be. I got into the gym and had to start lifting weights and pushing bars over my head and running on treadmills every single day. It all paid off. I loved learning all the physical stuff; doing martial arts centers you.”

One martial arts discipline that Ronan particularly appreciated was “wing chun, which we used a lot because Hanna would be fighting people bigger and stronger than she is, and would have to use their strength against them. But Jeff would also put Hanna’s own spin on the styles.”

Imada says that he followed Wright’s mandate to eschew an over-the-top fighting style in favor of “everyday, real moves that can be used in self-defense. So although she enjoyed knife work, we also taught Saoirse to work with no weapons.”

“It’s easier if you’ve got weapons,” comments Ronan. “But to me it was more like dancing than anything else; it’s still choreography, after all.”

Bana remarks, “Joe had made it clear early on that he hates seeing a lot of editing cuts in fights – as do I – and that there would be sequences where he wasn’t going to cut away. So the fight scenes in long takes, as we were doing, had to be accurate and planned out with Jeff and Joe.”

Following up on the memorable uninterrupted sequences Wright conceived and executed in Atonement, The Soloist, and the miniseries The Last King, in one key sequence in Hanna the camera tracks Bana through a long steadicam take. In-character as Erik, he goes below ground into a train station to evade a special ops agent, only to have to fight off four at once. That sequence alone – with its elements of martial arts and street fighting – made the movie “the most physical picture I’ve ever done,” states Bana.

Blanchett also took her action scenes seriously. She reports, “I told Jeff that I didn’t want to look like ‘a girl’ holding a gun. He reassured me that women holding a gun often look more natural than men doing so, since the women are not trying to emulate Clint Eastwood or a cowboy.”

Bana praises his fellow Australian, stating that “Cate’s interpretation of this villain is great. She is a fantastic actor to have hunting you down!”

Ronan adds, “Cate is someone I look up to. I admire her work ethic and her professionalism. Sharing a scene with her, she gives you so much – yet manages to be so contained and not give away too much when she doesn’t need to.

“Eric is a terrific actor and is lovely to be around. He is like a ray of light on the set. He’s hilarious, and would keep me smiling on the coldest days in Finland.”

With financial incentives and considerable logistical support from the North Finland Film Commission, Wright and the locations team selected for Hanna and Erik’s “neighborhood” a landscape of breathtaking natural beauty around Kuusamo, just on the south border of Lapland.

“It gave us such scale and scope, and it was magical,” says Greenwood. “We were 25 miles south of the Arctic Circle, and 25 miles from Russia. There were trees that Dr. Seuss could have sculpted.”

Some of the shooting sites were accessible only by snowmobiles. The vastness of the snowy wilderness also served to establish the physical reality of the characters’ existence and capabilities. Director of photography Alwin Küchler consulted with Finnish peers and crew beforehand to be prepared for camera complications in certain temperatures.

Sure enough, the temperature went as low as 33 below zero during the Finland shoot. “I prefer Irish weather, at least when it doesn’t rain,” muses Ronan.

Holleran recalls, “In the morning, the steam from the river covered people’s eyelashes and mustaches – among other things – in frost.”

Ronan notes, “Finland did bring out the fairy tale aspects of the story. We were shooting on a frozen lake, surrounded by pine trees covered in snow.

“But that kind of cold affects everything you do, especially in fight scenes which require muscle memory. In that first week of shooting, the cast and crew all pulled together fast.”

When not acting and/or fighting on-camera, Ronan and Bana were covered up in blankets and long capes; they had also been schooled beforehand about hypothermia risks, as part of local production company Helsinki Film’s careful prep work with cast and crew.

Shrugging off the cold were animals on call for this leg of the shoot, ranging from wolf puppies to snow foxes to reindeer.

Imada’s fight choreography was shored up to allow for the difficulties of the ground terrain. Bana remembers, “In sequences where Saoirse and I were stick-fighting, when the bamboo hits your knuckles in below-zero temperatures you really feel it…

“Truly, Finland and the other locations added so much to the film and enhanced this story’s qualities.”

From Finland the Hanna unit traveled to Bavaria, in southeast Germany, near the border with Austria. Filming took place around Bad Tölz, in the shadow of the Alps. The weeklong stint there was for interior and exterior scenes of Erik and Hanna’s log cabin. Temperatures were higher than those in Finland – enough so that a portion of the snow had to be artificially generated.

Lochhead marvels, “Walking onto the cabin set was surreal. I was surprised at how much of a physical approximation it was of what was in my mind when I wrote about it. The feeling was, I knew this place well and somehow this whole crew was aware of it.”

The screenwriter reflects that for him the story took shape beginning “with an image in my mind, of a girl running among the trees and hunting a reindeer. Then I tried to explain it as best I could. When I saw Saoirse in-character, I thought, ‘Wow. She saw into my head, too.’”

Elsewhere in Germany, filming took place at Berlin’s storied Studio Babelsberg, while Berlin locations stood in for CIA headquarters in Langley. Bana enthuses, “For me, there were no days in the studio, and it was exciting to film on real locations – including my swimming sequences!”

Continuing across Germany – a feat made possible for the production by local and regional subsidies through the German state feature film fund DFFF – the main location in Berlin was Spree Park, an abandoned amusement park in the East of the city. “An amusement park, after the lights are turned off and the glitter has faded, has a sinister air,” cinematographer Küchler notes appreciatively.

A boon to Greenwood and Spencer and their team, the now-derelict Spree is littered with disused rides, rusting structures, elaborately crafted animals, and vacant control booths. Within the grounds of the park, they constructed Grimm’s House, where Hanna encounters Knepfler (played by Martin Wuttke, who was seen as Hitler in Inglourious Basterds). The structure of the house intentionally mirrors that of the cabin in the woods, but the garish plastic figures and colorful décor are a long way from the naturalistic home that Hanna has journeyed from.

Hamburg’s infamous red-light district was the site of another location that would seem to have been ready-made for the film; Isaacs’ nightclub, which Marissa visits expressly to bring him into the hunt for Hanna, is portrayed by the Safari Club. The latter is the only remaining live sex club in Germany; it retains its vintage 1960s interior, which the production was not allowed to alter in any way since the décor is legally protected. Additionally, filming had to be completed by 10:00 PM so that the Safari could open for business.

Isaacs is played by Tom Hollander, whom audiences will recognize from numerous films including two prior for Joe Wright – that is, if they recognize him at all. Ronan muses, “Tom plays Isaacs in a way that I’d never have imagined from the script; it’s unique. I can’t say I admire the character’s dress sense, but I admire him for wearing those clothes – most of which Tom suggested to Lucie and Joe!”

On a higher aesthetic plane, the “observation area” that Hanna is sequestered in early on was designed as “an homage to Ken Adam’s brilliant ‘War Room’ set in Dr. Strangelove,” says Greenwood.

Filming next took place in Morocco, “where the thermostat twice reached 122 degrees,” says Holleran. “We quickly learned to wrap scarves around our heads to keep cool.”

The first stop in Morocco was in the deserts around Ouarzazate, a town known as the “door to the desert.” Moving into the center of town, cast and crew found themselves at work along the road of the Kasbahs, which runs towards Zagora and is the last stop for camel trains before Timbuktu.

“We could actually order 200 camels, and they would appear promptly,” remarks Greenwood. In addition to fashioning a camel marketplace, her team transformed an existing structure into a rundown hotel.

Audiences will get a good sense of the area, what with sequences where Wright again orchestrated sustained tracking shots with Küchler and the camera department.

Actor Jason Flemyng remarks, “When you’re part of a shot like that, the pressure is on – especially if you’re coming in at the end of it! We did well, because the one take that got messed up was because a camel smashed into the camera. It’s so exciting to be a part of that; there’s one reason I wanted to do a Joe Wright movie.”

Ronan reports, “There’s this beautiful shot of Hanna in the marketplace in Morocco that we hold the whole way through. Morocco has very intense heat and light; it was the greatest contrast to where we had started out weeks earlier, in Finland.”

The unit went across the Atlas mountains to the Atlantic coastal port of Essaouira, for another contrasting landscape; buffeted by winds from the ocean, Essaouira is a popular surfing destination and was one of the last places visited by music icon Jimi Hendrix.

“We brought Spain to Morocco,” adds Greenwood. “To film the [family’s] Spanish campsite there meant bringing over 50-odd tents. Pitching them and keeping them standing was a challenge.”

Morocco was the final location destination for the Hanna troupe, if not for Hanna herself; after Hanna makes her action-packed escape from confinement, she finds herself in the desert of Morocco, and is given a lift by a holidaying English family as she plans the journey north to Berlin to reunite with her father. Ronan notes, “It’s here where she first begins to see the real world, hears music, perceives television and much more.

“I loved filming with the family; I call them that because I could see how all of them – Olivia Williams, Jason Flemyng, Jessica Barden, Aldo Maland – were already close. Also, in contrast to the intense scenes with everyone else, Hanna’s ones with them are mainly comedic.”

Ronan plays many of them opposite fellow teenage actress Barden, fresh from stealing all of her scenes in Tamara Drewe. Barden “loved the relationship between Sophie and Hanna. They’re like two little flowers, and are intrigued by each other because they’re complete opposites.

“We all know someone like Sophie; she’s the popular girl at school, and it must be exhausting being her because she’s obsessed with how she looks. But she’s about to have the holiday where you grow up and then go back to school a different person.”

Barden notes that “working with someone so close to our own age, Saoirse and I got friendly; we’d sing Lady Gaga songs together all the time.

“Sophie and Hanna’s friendship in the movie is built around getting to know and understand why the other person is the way they are; their differences bring them together, and at the end of the day they’re both teenage girls trying to find their way in the world.”

Barden confirms Ronan’s intuition that the on-screen family had bonded off-screen. “When that volcano went off in Iceland, we ended up spending about 18 hours in a car together [traveling],” she reveals. “We got comfortable with each other.”

Her on-screen parents Flemyng and Williams couldn’t help but set that tone, for, as Flemyng quips, “I’ve killed Olivia, and I’ve divorced Olivia! You see, she and I have worked together so many times now and the dynamic of ‘our marriage’ is always the same; she’s in charge, and slightly disgusted about how I behave…”

Barden offers, “Jason is so funny that it was purely his fault when we would detour from the script. But Joe Wright liked how natural we were with each other, and encouraged that. He supervised the organized chaos of us.”

Williams felt that she knew her “character of Rachel very well; I’ve met this woman. There are several strong women in Hanna, and mine stands for motherhood – of a particular 21st-century kind, where you’ve read a lot of parenting manuals. Every member of her family thinks that Hanna is like them – and Rachel is no exception – and wants to write their own version onto the blank page that is Hanna.

“Joe lets actors have creative input. The more I talked with him, the more I had the slightly alarming feeling that anything you say in an unguarded moment – especially about your character – might end up in the script. And when you work with Jason, there is always room for improvisation…”

Flemyng clarifies that “Joe did let us improvise – or, as we actors call it, ‘nick bits.’ I said, ‘I’m going to be nagging at you and asking you questions,’ and Joe told me that it was fine and that actors who have no imagination are what drive him mad. As a director of actors, he’s very precise.”

Bana praises Wright as having “a great sense of humanity, as a person and in his work. He is able to communicate what the scene is about and what he sees in his head, but I know I will still be surprised along with audiences when I see the finished film.”

“Through Joe, this script comes to life in different and unexpected ways,” remarks Blanchett, who also feels that audiences will once again be impressed by the young woman playing Hanna. She states, “Saoirse is an extraordinary actor and an incredible presence, self-possessed and unaffected. She connects with things by drawing on her own experiences. She has a rare spirit.

“I had worked with her [actor] father on [the 2003 movie] Veronica Guerin. When I bumped into him at the Oscars ceremony in 2008, it was then that I realized that the little child who used to visit the set was one of the year’s nominees – Saoirse.”

No matter which challenging roles she takes on in the future, Ronan is now that much better prepared. “I’ve still got a few of the moves that I learned on Hanna,” she smiles.

Q&A with director Joe Wright

Q: What drew you to make Hanna?

Joe Wright: The script was full of particular elements of interest to me, with an atmosphere that I was intrigued by. But there was lots of space left in it, and I mean that as a compliment – there was space left for me to invest my own feelings and concerns.

First and foremost, what interested me was the character of Hanna; we don’t see enough films with a teenaged female protagonist. Thematically, I’ve always been intrigued by characters who are holy fools – like E.T., Chauncey Gardiner in Being There, and Kaspar Hauser in Werner Herzog’s movie – and who are not really of this world. Those last two, especially, have grown up in a world that doesn’t have the pressures of outside society and so-called civilization. They come into our world with an adult consciousness but with the naïveté of a child. I find it fascinating how someone like that experiences the world, because it offers us a subjective opportunity to see things afresh.

Q: So you wanted to put a character like that through their paces –

JW: Well, it’s about looking through their eyes. My work is generally quite subjective, from one character’s point of view; Atonement appears to be a three-stranded narrative, but actually the whole thing is seen through the prism of Briony’s guilt. I like fairly extreme “realities;” the schizophrenic’s in The Soloist would be another example.

Q: Perhaps you couldn’t have made Hanna until after you’d done The Soloist, because there’s a great deal of externalized activity to the character’s reality in that, which may have been good preparation for the action Hanna is central to in this…?

JW: Maybe. When one finishes a film, one never really knows what one has learned from it until one puts it into practice for the next movie.

For my craft, the action elements of the story did attract me. I’ve always thought of action as being pure cinema, because the same effect can’t be achieved in any other medium; dialogue can be played out onstage or on radio, and beautiful pictures can be photographed or painted. Apart from sports coverage, there isn’t anywhere else that you can find anything like it.

I wanted to experiment with the visceral impact, delivering it but perhaps in a slightly different way. I was thinking back to the French New Wave, and Robert Bresson’s Pickpocket. Those sequences where the pickpockets are at work are extraordinarily beautifully choreographed action sequences. By which, I don’t mean with fighting and punching and kicking; you’re telling the story through the actions of a body, of a character.

For a far more personal reason, what drew me to Hanna was its female protagonist. A very dear friend of mine was raped around the time that I was reading the script, and I was so angry; I had been thinking about how women are placed within society, and about what it means to be a young woman in today’s cultural climate. I look around, and I wonder whatever happened to feminism; it wasn’t meant to be a passing fashion, it was meant to change the world forever. I’m appalled by the sexualization of teenagers, and by Hello! Magazine culture. These things scare me. There was an impulse to create, as a response to what happened to my friend, a strong female character who had grown up outside of gender sexual politics, who had never met another woman, never seen advertising nor had a clue what lip gloss was.

I was interested in juxtaposing Hanna with the [vacationing] family – especially Sophie and [mother] Rachel. As a creature of today, Sophie is a contrast to Hanna. I wanted to explore these two different images of teenage girls. Sophie is ridiculously infatuated with the whole prevalent teenage girl culture, and I saw in Rachel a lot of women I know – of my generation and a bit older – who have lost their way in terms of their feminist socio-political ideals. I worry for them, and for their children too. A bit heavy, but that’s what I was thinking about…

Q: Hanna’s most extensive scenes with another female character are those with Sophie. Both of the actresses, Saoirse Ronan and Jessica Barden, perform at a high caliber.

JW: I would let Saoirse and Jessica take the lead; the kiss between them was suggested by Saoirse. She said she thought it was what Hanna would do. Saoirse and I also talked about how Hanna has no preconception of what is beautiful and what is ugly. Everything just is what it is; one of the core aspects for us, which Saoirse portrays beautifully, was that Hanna judges no one. That’s anathema to most of us, as we are brought up and taught to constantly judge people, places, and things against ourselves, our aspirations, and our fears.

Q: Around the time of Atonement, you said that Saoirse has the empathy to feel and express the emotions of another human being. But how did you both prepare her to play this unique character?

JW: Going back again to what drew me to make this movie, the real deal-breaker was Saoirse; if she hadn’t been involved, I’m not sure that I would have felt confident in going ahead with the film. Once I knew that she was on board – and had wanted me to direct – then I felt, “We can do this.” Because my safety net was, you can just put the camera on Saoirse in close-up – what she’s thinking – and that will see you through a scene.

But Saoirse and I talked lots, including about emotions. On Atonement, she and I started with just how Briony might walk. The character grew from the short, precise, controlling steps that she made. On Hanna, we worked with [stunt coordinator and fight choreographer] Jeff Imada to create a very centered being, someone who stood grounded and balanced with a relaxed yet good posture. Hanna doesn’t have the nervous twitches or slanted shoulders that come from years of social interaction. [Laughs]

Her movements as Hanna are quite aerodynamic, though I was forever telling Saoirse to hold her elbows in when she ran; she has that natural tendency to flail them about

Hanna doesn’t move unless, or until, she has to. Her eyes don’t “find” something; they go straight to it. She also doesn’t really make any outward facial expressions, apart from when she’s fighting and becomes almost animalistic – with snarling.

The voice was quite important as well; once Saoirse had the centered physicality of Hanna, she found something of an ethereal voice for the character. At the same time, I got her to lower her voice about an octave or two. That made Saoirse feel slightly more of the earth; therefore, she was simultaneously capturing the earth and the air that characterize Hanna. At 16, Saoirse now has even more of a handle on her craft than she did at 12.

Q: With Marissa, we’re seeing a very different Cate Blanchett portrayal…

JW: Marissa is kind of based on a primary school teacher I had! Her name was Priscilla, and she was sexy and well-kept. She wore thick make-up and stockings that had a sheen and made noise when she walked. At story time, the girls used to sit and stroke her legs as they sat around her. She had this vibe, and she came to mind when I was thinking about Marissa; since Hanna is also a fairy tale, I was conceiving of the characters as archetypes and then layering them with character specifics. So Marissa was a combination of Priscilla, President George W. Bush, and a wicked witch; in my parents’ puppet shows, the witches had red hair and wore green, so I asked [costume designer] Lucie Bates to always have Marissa wearing green, and the red hair suits Cate very well I think.

Cate is not a vain actor at all, and was up for wearing too much make-up; I wanted to see the pores through it. The teeth thing –

Q: The obsessive flossing and brushing –

JW: That comes from what I see as the American obsession with teeth, really. From an English person’s point of view, it’s extraordinary how uniform American teeth are. So I thought Marissa would take it almost to the point of harming herself. I spoke about that with Cate. Later, in the middle of one shot she sucked her teeth and made this strange little noise. I watched it thinking, “This is fantastic; Marissa is tasting the blood of this moment.” It gives her a thrill.

Q: Why or how did the fairy tale take come to you?

JW: Because it could work on a number of levels throughout. The theme park at the end is one of the most literal fairy tale references, while the tune that Isaacs whistles is one of the more atmospheric ones.

Then there’s the idea that Hanna flicks a switch and changes her destiny, for instance – that’s like, will she drink from the chalice? We made the box and the switch big and red.

The story as a whole has a lot in common with fairy tales like the Little Mermaid or Hansel and Gretel. There’s a family – of sorts – living in a wood cabin in a forest, and rites of passage unfold in the story; the child has to leave the house and go into the world, and experiences and meets evil – which has to be overcome. Fairy tales to me are never happy, sweet stories; they’re moral stories about overcoming the dark side, the bad.

In terms of characterization, Erik is the archetypal fairy tale father. He’s an earthy woodcutter – like Rapunzel’s father – and they live in the forest. Erik has the spirit of the trees in him, and Eric Bana was able to play that. My dad was a wood carver as well as a puppeteer, and he used to say that people of the wood have that spirit.

David Lynch is a hero of mine; I first saw Eraserhead and Blue Velvet as a teenager, and they blew my mind. So his twisted fairy tales were a big influence. In Hanna, I finally had the opportunity to play around; there was no room in my other movies for more surreal storytelling.

Q: Did you feel you could do so when reading the script for the first time – or were those elements already in there?

JW: It had that beginning setting, but it wasn’t until later that I read an earlier draft by Seth Lochhead – which was far more Lynchian than the draft that I first read, which had been reined into a more conventional thriller with more about the CIA. I couldn’t care less about how-did-so-and-so-find-out-that-piece-of-information-about-such-and-such.

Q: Given that you were going to impart a fairy tale aesthetic into an adventure thriller, did you map out everything on storyboards?

JW: Only most of the action sequences; I would have liked to have storyboarded more, but there wasn’t time in our fraught pre-production period. I was less prepared with this movie than I had been with any other previously. Because of the distances between locations, it was difficult to fully prepare. [Production designer] Sarah Greenwood and I would have discussions with photographs as references, but things had to be improvised.

So I decided to use that to my advantage, to try and have a looser creative response to what was happening rather than worry that I was losing control. I had to think more on my feet and tap into my subconscious.

Q: You’ve always had such logistically complex shots in your movies – Skid Row in The Soloist, Dunkirk Beach in Atonement…Which were the most difficult on Hanna? Was it the tracking shot from above-ground to below-ground fighting with Erik?

JW: That one – the orange-tile one – was pretty tough, but I think the container park action sequence is probably the hardest thing I’ve ever done. In part because so many people were involved in the action elements, and not all of them were stunt people. I like setting myself those challenges.

But it’s often out of necessity, not as a stylistic choice, that I do those steadicam shots; if I were to have done the orange-tile fight with coverage and action cuts, that would have taken two days to shoot – and we only had one day, for everything including the above-ground exteriors. What I find is that if you devote enough time to rehearsal, then the actual shooting time becomes much quicker. Also, with all due respect to Paul Greengrass – who I think is a genius – I wanted to avoid the style that he developed for the Bourne films, because it has been copied innumerable times since.

Q: Paul Tothill has edited all your movies. Did Hanna pose any new challenges for you two in post-production?

JW: It was a joy for Paul and I to edit action with very little dialogue. If – as I mentioned before – action is pure cinema, then cinema is montage and editing; action is created in the edit. I love sound-editing as well.

Q: What do you hope audiences get out of this movie?

JW: A lot of fun from a piece of pure entertainment. And I hope it freaks ‘em out just a little bit, too.

Hanna hits theaters April 8th, 2011.