The past is a home country in Corsica-born French director Thierry de Peretti’s second feature, A Violent Life. A crime saga chronicling Corsica’s gruesome 1990s nationalist feuds via the rise and fall of the lost generation who took part in them, it captures a topic seldom shown on the big screen, but a few scattered hints of old and recent mafia classics aside (from Coppola’s Godfather trilogy to Francesco Munzi’s 2014 Black Souls), the end result never quite feels like the gripping thriller it could have been.

The entry point in the island’s troubled decade is Stéphane (played here by newcomer Jean Michelangeli, in an assured debut). A bespectacled and tame-looking Paris-based Corsican, his cushy life in the capital takes a U-turn after an old time friend is murdered in the island by local thugs. Shaken but seemingly not surprised by the assassination, he ignores his mother’s advice and makes his way back to Corsica to attend the funeral, a Michael Corleone-esque trip home that plunges A Violent Life into a long flashback to the eponymous gruesome years that shaped Stephane’s transition from bookworm intellectual to armed insurgent.

De Peretti follows his transformation in rigorous chronological order. As A Violent Life flashes back to 18-year-old Stéphane, the teenager shows a penchant for political discussions and a deep-seated anger for the way his father’s generation betrayed Corsica’s independence. It’s the kind of parents-sons bellicosity you’d expect in a 1968-themed film, and it fuels Stéphane’s angst to take up arms. Caught with a bag of guns he’d agree to hide on behalf of some criminal friends, and eventually sent to prison, he is recruited by fellow inmate and veteran separatist François (Dominique Colombani), who brainwashes the youngster into joining the armed struggle for a free Corsica.

For those acquainted with Jacques Audiard’s A Prophet, Stéphane’s radicalization may strike as a familiar – if markedly less gripping – rendition of Malik/Tahar Rahmin’s own. An avid reader and role-model inmate, the novice yardbird starts befriending fellow Corsicans who condemn his bourgeois apathy and expose him to the colonial dimension of the separatist movement: the war with metropolitan France is a struggle between an imperialist power and a defiant, untamed Other. They are fluent in Marxism and Frantz Fanon, call their group “the structure,” and embrace belligerent slogans that sound like sinister self-fulfilling prophecies: “we have to be radical… everywhere needs cleaning up.”

Where A Violent Life works best is in the fine balance de Peretti strikes between universal and particular. Watching Stéphane persuade his old time friends to join the resistance, while François methodically articulates the insurgency’s ideology and struggles to keep mafia groups away, de Peretti offers an eye-opening, near-ethnographical insider’s look into one of Europe’s most obscure independence movements. The inclusion of footage from the 1990s clashes between the insurgents and French authorities neatly complements Claire Mathon’s vivid cinematography to give a naturalistic, almost documentary-like feeling, while the choice of language – characters speak a blend of French and native Corsican – adds verisimilitude to the drama.

Still, context-specific as it may be, Stéphane’s recruitment touches upon topics that transcend its geographical settings. The radicalization the young man undergoes and the questions he is asked in his peer-pressured transition into armed insurgent (“what are you willing to do for your country?”) ring achingly true in light of today’s struggles against youth’s radicalization in continental Europe – and beyond – as they did in 1990s Corsica.

It comes as somewhat frustrating that the reasons to praise de Peretti’s work are also implicitly part of its shortcomings. Narratively complex and plot rich, A Violent Life stalls in its breadth of ideas. The story gets swamped in too many details, Stéphane’s revolutionary training feels too verbose to be engaging, while new characters keep entering and leaving the scene, making it difficult to identify who’s who as the feature hits its climax. Worse, Stéphane lacks the charisma needed for his transition from a Gramsci-like intellectual into rebel to feel credible (though this is more de Peretti and co-scribe Guillaume Breaud’s fault than Jean Michelangeli’s own). By the time the youngster returns to his native island and de Peretti’s second feature comes to an end, A Violent Life has conjured up a judiciously shot drama that nonetheless feels as distant and at arm’s length as the island and the generation it portrays.

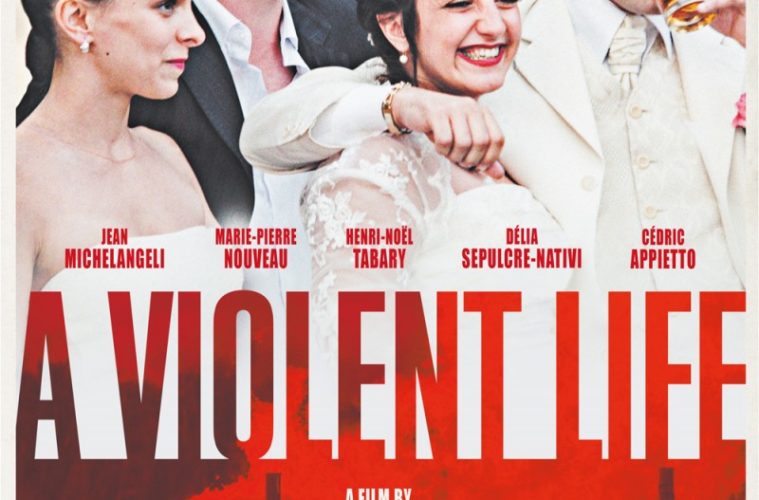

A Violent Life played at New Directors/New Films and hits VOD/DVD on April 24.