Dailies is a round-up of essential film writing, news bits, and other highlights from across the Internet. If you’d like to submit a piece for consideration, get in touch with us in the comments below or on Twitter at @TheFilmStage.

Jean-Luc Godard‘s Goodbye to Language, was named best picture of the year by the National Society of Film Critics, Variety reports.

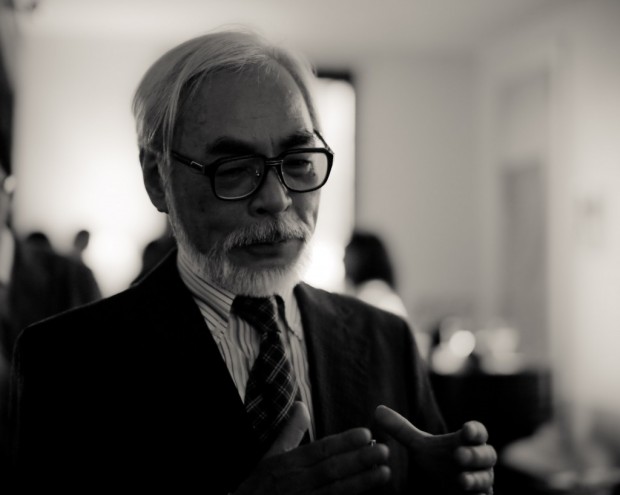

On Hayao Miyazaki‘s birthday, watch a 1.5-hour conversation with the legendary director:

Little White Lies chats with Denis Villeneuve for Enemy’s U.K. release, a film we recently named among the top 50 of 2014:

My fear is not about that. The movie is a warning. If you don’t deal with your shit then your shit will stay alive. It’s really about the fact that I’m afraid that there’s power from inner anger and inner fears that are coming from the past that are stronger than our will and that they can mislead us and that we are not really free in some ways. That is my biggest fear in life right now because it is a big barrier between a human being and their real adult life. It’s something that as a human being I’ve been struggling with a lot and as an artist too. For me it’s more about this idea that the spider will come back at the end.

Watch a video essay on the visual techniques of Alfred Hitchcock, incorporating all four decades of his feature films:

At Badass Digest, Evan Saathoff on Punch-Drunk Love and the sorrow of disliking Adam Sandler:

Written and directed by Paul Thomas Anderson specifically for Adam Sandler, Punch-Drunk Love takes everything funny and weird about Sandler and transforms it into a character that touches on the romantic, the tragic, even the heroic — three sides to Sandler no one had any right to anticipate. And yet it’s all there. This isn’t a stunt role; it’s the flipside of everything Sandler represents as a comedian. By making Sandler’s character, Barry Egan, a stunted man-child with severe emotional issues, Anderson offers viewers an alternative perspective on who Adam Sandler is and how his persona functions, making even the worst of Sandler’s films a bit more interesting as a result. The funny violence is no longer a joke. The childlike affectations are no longer silly. The almost painful shyness is no longer cute. Just as Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive exposed the possible ugliness that comes with taking silent action heroes literally, so does Anderson reveal the pathos inherent to a personality like Sandler’s, and it’s amazing.