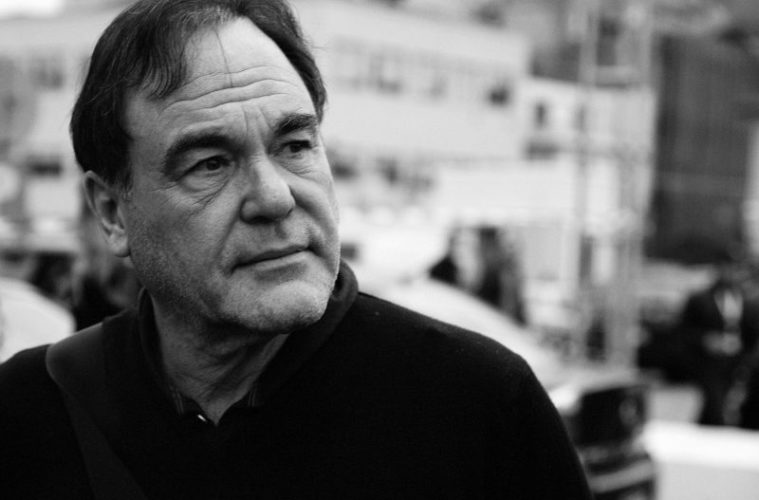

It’s safe to say Oliver Stone isn’t exactly fashionable these days, a matter apparent in how the trailer for Snowden instantly became a punching bag on this writer’s Twitter feed. Yet film critic Matt Zoller Seitz’s behemoth of a book, The Oliver Stone Experience, should, with any luck, shift the conversation. Framed as a series of interviews with Stone conducted over the past half-decade or so and interspersed with everything from personal photos to studio-executive notes to archival reviews, this feels like the definitive text on someone once at the center of American cinema. It might not change anyone’s mind on Stone’s films, but with the man being such a raconteur, you’ll still find yourself tearing through it.

We were lucky enough to chat with Seitz over the phone about his undertaking, as well as some thoughts on American politics and cinema in general.

The Film Stage: Reading your book, a comparison came to mind for Stone; Samuel Fuller. He was a soldier, journalist, pulp writer, and filmmaker. Is that a fair comparison?

Matt Zoller Seitz: I think that’s a very fair comparison. In fact, we talked briefly about Samuel Fuller, particularly The Big Red One. It’s a memoir of his service in the pacific in World War II. Of course, that movie came out 35 years after Fuller’s experience, and Platoon came out approximately 20 after Stone’s in Vietnam. That’s a fair comparison. And, also, the left-wing politics.

You bring up the various criticisms Stone has received on a number of his films regarding treatment of certain ethnicities or female characters. But now that we’re in an age where films are judged far, far more on the basis of ideology, how much worse do you think these controversies would’ve been today?

I don’t know if they would’ve been better or worse, but they would’ve been more immediate, I think. I think people kind of forget nowadays that movies open on 2,000 screens and then they’re gone in a month. Everything happens faster now, like the way movies are released and the reaction to them on social media. Back in the day, Platoon played in a lot of theaters for three months, six months — nine months, in some cases. And there was plenty of time for a reaction to sort of build, and it happened in slow-motion. I don’t necessarily know if it would be worse, but certainly it would be more simultaneous.

There’s a part of the book where Stone remarks “I’m getting deeper into the shit-hole every time I talk to you.” How difficult was the process of getting him to be as open as he was?

It wasn’t really that hard; he’s a pretty open guy. If you go back and read the interviews with him dating back to the early ’80s, he’s pretty open then, too. He’s an open book, and one of the original titles we thought about for this was Oliver Stone: An Open Book. I would say the biggest problem I had while interviewing him was keeping him on track, because Oliver has a very wide-ranging imagination. He doesn’t stick to one subject for very long; he’ll jump all over the place.

It wasn’t really that hard; he’s a pretty open guy. If you go back and read the interviews with him dating back to the early ’80s, he’s pretty open then, too. He’s an open book, and one of the original titles we thought about for this was Oliver Stone: An Open Book. I would say the biggest problem I had while interviewing him was keeping him on track, because Oliver has a very wide-ranging imagination. He doesn’t stick to one subject for very long; he’ll jump all over the place.

In your introduction, you state how Stone’s films were instrumental in your political awakening, particularly your disillusionment with Ronald Reagan’s values. Obviously, as you note in the book, Reagan was enormously popular — the 1984 election was a massive landslide — but what was the point where you started to sense his ideals were of less value to the American people? Was it before Bush’s loss to Clinton in ’92?

It was a little bit before that. I think it was probably when he announced the Star Wars initiative, which was in 1987. I remember: it was on the cover of one or both news weeklies and I was standing in 7/11 as a high school kid thinking, “We’re really going to commit billions of dollars to a system that can shoot missiles out of the sky when we’ve got so many other things to be spending money on?” Like, it’s still going to be armageddon; like, it’s going to be half the earth instead of all of the earth if we can shoot down their missiles and they can’t shoot down ours. It just seemed insane to me. That’s when I think it started to turn, but Stone was going along a similar tract. In fact, he says in the book that he was a Republican when he was younger; he inherited his father’s values. His dad was a stock-broker.

He voted for Nixon, and although he had certain questioning tendencies after the war, they didn’t really coalesce into anything coherent until about 1984/85 when he started taking trips to Central America to research what would later become Salvador. When he saw what was going on there — when he saw students, he saw kids, he saw teenagers fighting in service of the right-wing forces down there, wearing uniforms not too different from the ones he wore in Vietnam — that’s when he started to question things a little more. And it’s funny, because Stone is often attacked for being incoherent, but he happens to be quite coherent, and I happen to agree with a lot of it, that he believes that military expansionism after World War II has driven a lot of this country’s decisions, and it’s not just the decision of who to invade and who to occupy, but also whose bank account is the fattest. A lot of defense contractors and business owners have a stranglehold over our legislature. And it’s the kind of thing where, if you mention them, well, a lot of people go to the movies to escape that kind of thing, so it’s no surprise that Stone has had trouble getting financing for questioning movies.

Stone mentions Reagan and Bush plenty throughout the book, but do you think any of his films were a response to the Clinton administration?

Not so much. I think that maybe, if you stretch a little bit, you could say U-Turn and Any Given Sunday might’ve been, if only because they express the casualness of corruption. He didn’t have too many nice things to say about Bill Clinton when I talked to him. He saw him as a guy who posed as a liberal but actually continued a lot of the policies of the Republicans, and I think that’s probably accurate. I think more of his concern is with the military-industrial complex — not just on foreign policy, but our own self-image. The national self-image is that of righteous warriors who go and intervene in situations to make things right, and that’s often cover for much more base motivations, and that’s what drives him. And that’s been, until fairly recently in our history, something that’s a lot more of a Republican thing, although certainly he criticizes Lyndon Baines Johnson for escalating the war after Kennedy’s death in JFK and Born on the Fourth of July explicitly.

You repeatedly state how much Stone’s films resemble the personal epics of ’70s American cinema. But does looking at Stone’s films from the ’80s give you a greater appreciation for the American cinema of that decade? Because, if you ask me, it looks like a Golden Age compared to now.

I mean, yeah — it does. But almost everything looks like a golden age compared to now. Personal filmmaking on a big scale has been largely driven out of movies. It’s really sad, and it’s even sadder when you hear people still defend American cinema as an art-form that’s superior to American scripted television. It’s like, what do you have to defend that with, really? Some indie films, maybe an occasional Scorsese or Spielberg, but that’s about it. It’s really depressing, and I think the ’80s look a lot better. I came of age in the ’80s, and that was my decade to come of age as a movie-goer. But I’m a little appalled by the quality of storytelling in some of those movies.

This is the age where they discovered MTV, fast cuts, music montages. I remember, even as a teenager, watching movies like Flash/Dance, Footloose, and Top Gun and going, “These don’t feel like movies to me. They feel like advertisements or music videos.” But there was a lot of stuff going on at the same time that were very expressive: there was Stone’s films, but there was also Jim Jarmusch, and Robert Altman was making some interesting work in the ’80s. Although he’d fallen out of favor by then, all his theatrical adaptations were extraordinary. And then you had people like Alex Cox that were very much working in Oliver Stone’s tradition.

Every once in a while, we get a Zero Dark Thirty or American Sniper — a political film that enters the zeitgeist. But it seems like politics in mainstream cinema is basically reduced to exploitive 9/11 imagery in superhero movies. Are Stone’s kind of films just not what we want to see? Are we collectively running away from trauma?

Well, I wouldn’t say “running away from it,” but we’re transforming it into something we can handle. There’s been a lot of disaster films and giant-monster films, like Pacific Rim, and superhero movies are all a manifestation of this shock after 9/11, and also the political fall-out after it. But it’s all very incoherent and self-serving, and there’s nothing in any of these movies as self-lacerating as anything Oliver Stone puts in any of his films in the ’80s or early ’90s. The subtext of a lot of superhero films is how good individual people are. There’s always one big bad guy who’s really bad, and if only the good guys can get their act together, they can beat him. There’s really no difference between that mentality and the one that got us into Vietnam and other wars.

I don’t really see a lot going on. I see, as you say, a lot of exploitation of imagery of fallen buildings, but I don’t see anything resembling a single coherent political thought in those films, which is very sad. I don’t know what to do with American movies. Occasionally, I’ll come across something that really excites me, but, even if it excites me, it’s not in terms of the view of the world it presents. It’s more that’s an interesting way to tell a story or that’s an interesting shot. It’s been a long time since we’ve had something as shocking and innovative on the level of JFK.

The Oliver Stone Experience is now available through Abrams.