Following The Film Stage’s collective top 50 films of 2025, as part of our year-end coverage, our contributors are sharing their personal top 10 lists.

To exemplify my year in one horrific-turned-hilarious example: I broke my hand in a moped accident on my last day covering the Cannes Film Festival, and the little-publicized power grid hack that took out the city, internet, and cell service across the region the next day kept me from visiting a hospital until I made it back to New York over the course of two miserable budget flights and one all-night layover. The crazy part is, I broke the only bone in my hand that doesn’t heal on its own, which meant my first surgery and a couple screws that will stay in my hand forever. The crazier part is, a banana caused the accident. That Mario Kart weapon is no fucking joke. I ran right over it driving straight and the next thing I know I’m careening across the asphalt as my moped rental scrapes past me through an intersection. I wouldn’t have known unless the Italian man who witnessed it hadn’t run up to me with the peel in his hand and a propulsive inability to stop laughing over the absurdity of it all.

But the craziest part? The banana that bested me was the very same banana I’d left on the foot floor of the moped for the better part of two weeks, first as a mistake and then out of sheer amazement that it hadn’t fallen off (even more, that it might have become a good luck charm of sorts). I can only imagine what debilitated state I might’ve ended up in had it finally fallen off on the highway stretch of my otherwise blissful daily trek between Antibes and Cannes. And when I think of it that way, I feel lucky. I’m here typing, aren’t I?

That doesn’t crack the top five worst moments of my year (at least I can laugh about it), but to wax any more about my self-made misfortunes feels like a bad omen—an open invitation for an even greater curse than the one I’ve created for myself. So, onto cinema, a consistent light in the darkness of 2025 and a yearly reminder of the greatest, and perhaps only, existential truth: all things must pass.

It’s my fifth year writing my top ten feature for The Film Stage, and I’m as grateful as ever for Jordan’s enthusiasm to host his contributors’ year-end reflections. In terms of The Film Stage’s coverage of the year’s best cinematography and performances (and 2026’s most anticipated films), I wrote about a slew of pictures within the links, and a number of my reviews, interviews, capsules, and essays are linked below to their respective films or quoted. Personal writing highlights include: an interview with Ronan Day-Lewis on his debut feature, a technological unpacking of the 28 [Units] Later series, a primer on Darren Aronofsky’s career, an interview with Oscar-winner Daniel Blumberg on his score for The Brutalist, an essay on the avant-garde torch carrying of modern music docs, and six color theory excavations for Paste on Brokeback Mountain, Punch-Drunk Love, The Lobster, Midsommar, Barbarian, and The Royal Tenenbaums.

Honorable Mentions

How long a best-of list should be only depends on how many films deserve viewers’ attention in a given year. Whether it’s 10, 20, 27, 39, 50, it doesn’t matter. All that matters is highlighting the films of the year that left a mark, for one reason or another, and in the modern deluge of good-to-great films coming out consistently across the world, there are 32 movies that don’t crack my top ten that still deserve a shout and your eyeballs. I’ve separated them into three honorable mention tiers, ranked against each other but unranked within their respective groups.

Last 12 out: (#31-42): The Actor, Die My Love, Megadoc, Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk, Hamnet, Splitsville, A Poet, The Testament of Ann Lee, Anemone, The Naked Gun, Dead Man’s Wire, Caught Stealing

Middle 10 out (#21-30): Cover-Up, Familiar Touch, Black Bag, Bugonia, Eddington, Train Dreams, It Was Just an Accident, Sentimental Value, If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, Sorry, Baby

First 10 out (#11-20): BLKNWS: Terms & Conditions, Pavements, Caught by the Tides, The Ice Tower, One to One: John & Yoko, Sound of Falling, Apocalypse in the Tropics, The Plague, Peter Hujar’s Day (see: review in print via Little White Lies), Below the Clouds

This year, I’m shirking the typical countdown in favor of a two-tiered alphabetical ranking (or five, if you include the three tiers above). There were five movies I saw this year that, depending on the day and mood, could and should be #1. They’re so stylistically disparate and uniquely profound that it’s more accurate to align them as equals. The same goes for the next five (#6-10), in a tier slightly lower than the top five.

The Back Five (#6-10)

Marty Supreme (Josh Safdie)

A film about a one-track mind so stubbornly determined, so proudly unwilling to do anything beneath his lofty and unfunded dream, that he chases the dream away headstrong, only to find himself in a cesspool of sour enemies accepting the lowest of the low, the consolation of all consolation prizes, with what shred of dignity (or pride) he has left. Until he returns home to one of life’s rarest graces—a second chance—in a new arena, with a new perspective on life forged by the fire of the fresh hell he created for himself. Between The Smashing Machine and Marty Supreme, the Safdie-bros-gone-solo have made two things clear: 1) they love telling stories that revolve around sports, and 2) Josh is the director. It might not be possible to one-up the fever dream anxiety of following Howie in Uncut Gems, but Josh has matched it in his cinematic pursuit of Marty.

The Mastermind (Kelly Reichardt)

My Cannes review of Reichardt’s downbeat beauty for The AV Club here. And my capsule from The Film Stage’s Best Cinematography of the Year: Kelly Reichardt first worked with Christopher Blauvelt in 2010 on Meek’s Cutoff, and she’s never looked back. The Mastermind marks their sixth feature together and proves the collaboration is only getting stronger. In a marked departure from past work (consider the natural vibrance of the similarly located First Cow), their film about a bored, hapless husband who resorts to art thievery for a kick––much to his remorse––takes on a barren, cheerless Northeastern gray. With unsaturated color and a pervasive silhouetting glow that would make Llewyn Davis proud, Blauvelt plays perfectly into the dour mood of Reichardt’s screenplay.

Pillion (Harry Lighton)

My capsule from The Film Stage’s Top 50 of the Year: Dogs Don’t Wear Pants finally has a companion piece. Harry Lighton tackles the duality of sexual attraction head-on in a gay sub-dom debut that shocks, tickles, delights, and devastates in equal measure (but not without pulling viewers out of the emotional quicksand it creates). In his edgiest career turn, Harry Melling plays Colin, a hushed, soft-smiling, barbershop-quartet-singing submissive who’s yet to find a man that really gets him—a bad biker clad in tight black leather that holds him by the thick chain around his neck and gives the dog the open couch seat while making him sit on the floor. Enter: Ray (Alexander Skarsgård), the tall-walking, rarely talking epitome of sizzling-hot dominance. The desired degradation opens Colin’s world as wide and willfully as his mouth, offering a deeply romantic enlightenment angle on the BDSM lifestyle that few films have deigned to take.

Việt and Nam (Minh Quý Trương)

My review of the hypnotic gay drama for The Film Stage here.

Who by Fire (Philippe Lesage)

Lesage captures heartache and betrayal like no other—in a dense, isolated forest that deafens the bawling, backstabbing, and shouting that emanates from it through an unwieldy story following a menagerie of characters and conflicts. My capsule from The Film Stage’s Best Cinematography of the Year: With unforgettable, long-developing shots that traverse stretched out dinner tables, rich natural landscapes, slate-gray roads, and dark, wooden rooms (not to mention the entirety of the B-52s’ “Rock Lobster”) Balthazar Lab’s cinematography on Philippe Lesage’s sleeper great stands out among the film’s most impressive characteristics. Lab’s immaculate eye is matched only by his sensibility for duration. Under Lab, the stunning cool-hued gleam of the woods swallows the many characters stuck in them. Even in the shadowed warmth of the cabin, there’s a coldness to Lab’s work––the kind that reflects the bitterness of young love, complicated pasts, and iced-over drama that finally cracks.

The Top Five (#1-5)

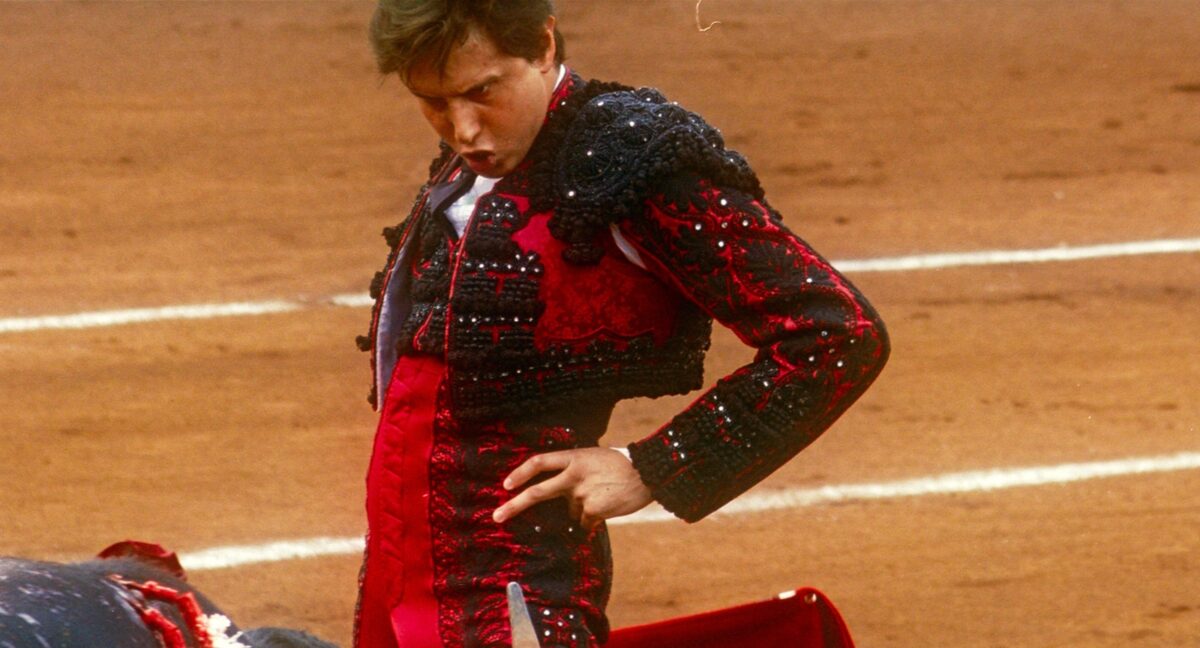

Afternoons of Solitude (Albert Serra)

Sometimes the most significant films are the hardest to watch because they open our eyes, and the truth, when tough to swallow, can sting something awful. Heart-wrenching and gutting in more ways than one, Albert Serra’s captivating documentary on the downright sickening tradition of Spanish bullfighting––and the foolhardy machismo of the celebrity toreros that drive its popularity––is shot like a dream despite capturing a living nightmare in well-deserved excess. Its graphic nature is not for the weak of heart, or stomach, but if you can handle the sight and duration of gamelike medieval slaughter in modern times, it will shock you awake to one of humanity’s most shameful pastimes. My jaw was on the floor from start to finish. My capsule from The Film Stage’s Best Cinematography of the Year: Artur Tort has fashioned a fresh wave of unflinchingly bleak and beautiful cinematography in 2025 that glows with the saturated violence of its subjects: colonizers and killers. Between Albert Serra’s Afternoons of Solitude (a disturbingly intimate documentary on the vulgarity and pride of the cruel and long-outdated tradition of Spanish bullfighting) and Lav Diaz’s Magellan (a pioneering and occupational epic ripe with extended duration and cameras that don’t move unless something is moving beneath them) the 35-year-old savant has more than proven his eye for lensing and framing in various styles and aspect ratios. He captures each film distinctly, but there’s a dense thematic through line that connects them in brutality and humanity’s fierce lust for power.

The Love That Remains (Hlynur Pálmason)

My review of Pálmason’s gentle, painful impressionistic masterstroke here. And my capsule from The Film Stage’s Top 50 of the Year: Imagine an Icelandic Sally Mann early in her career, desperate for attention from the high-art community. She lives off the land in a remote countryside and relies heavily on her five-person family to make her art. But instead of capturing her life with a camera, Anna writes with the extended duration of the sun; instead of silver-screen prints, she cuts and produces metal art that gestates spontaneously outdoors across entire seasons. Now, with all of that in the background, imagine a heartwrenching separation unfolding over a year’s time, one with three children at the center, clashing ideologies in tow, and well over a decade of resentment and remorse wrought by the laziness of a fisherman husband who hasn’t held up his end of the bargain in existential ambition or self-care. Hlynur Pálmason’s magnum opus (to date) is about exactly what it sounds like: the love that remains between ex-partners––in its shredded, preserved, bitter, adoring, simple, altogether impossible complexity––and the possible futures that can emerge.

Magellan (Lav Diaz)

Filipino writer, director, editor, production designer, and cinematographer Lav Diaz is a filmmaking machine that cranks out lengthy micro-budget experimental wonders that rarely ever cause an international stir, even if they should. But that machine never works within the Hollywood system, or even the much more reasonably financed European system. He’s still nowhere near Hollywood (and that’s certainly by choice), but he makes his first expedition into popular territory with Magellan, produced by the European wundertroupe Marta Alves, Joaquim Sapinho, Montse Triola, and Albert Serra (also responsible for Afternoons of Solitude and Misericordia this year) and led by global superstar Gael Garcia Bernal in what is undoubtedly – and I don’t say this lightly – the best performance of his career. It’s a mystical, majestical take on a colonizer in decay that simply can’t be missed. My review for The AV Club and my interview with Laz Diaz for The Film Stage are coming soon.

One Battle After Another (Paul Thomas Anderson)

In the least surprising co-#1 on my list sits PTA’s universally beloved revolution comedy adventure epic, the first of its kind from Anderson, whose historically small budgets (relative to living Hollywood greats) were left in the dust of the San Fernando Valley in place of devastating and riotous car chases (yes, there are both kinds), riveting action sequences, highway rollercoaster cinematography we won’t ever forget, an iteration of The Dude that will go down in film history just as significantly as the OG, an introduction to a new star in Chase Infiniti, and the most delightfully bizarre performance of Sean Penn’s 45-year career. Though the epic storyline, starry cast, immaculate sense of storytelling, and singular blend of comedy and drama is prototypical PTA, the approach to filming it all feels like the beginning of a new accessible chapter in his filmography. Or, if not, a fantastic tangent that the public will talk about more than any other PTA film to date. My capsule from The Film Stage’s Best Cinematography of the Year: From Chief Lighting Technician and Gaffer extraordinaire (with credits like Training Day, Munich, Iron Man, The Bling Ring, and Good Night, and Good Luck to his name) to co-DP alongside his boss and regular collaborator Paul Thomas Anderson on Licorice Pizza, to One Battle After Another––his first official solo DP credit on a feature––Michael Bauman has skyrocketed into significance through his work on PTA films, which began in 2012 with The Master. Hitting various new aesthetic highs in OBAA, Bauman’s silvery VistaVision camerawork (courtesy of Giovanni Ribisi) shines in too many sequences to name here, chief among them the floating rollercoaster framing of ever-dipping and -rising asphalt, the contrasting wide and tight lensing of revolutionaries in-action and on-the-run, and the winding oners that ground the story’s gutbusting goose chase.

Sirāt (Oliver Laxe)

Oliver Laxe’s explosively bleak thriller is a grimy, EDM-fueled, LSD-laden rollercoaster ride alongside a magical mystery tour of vagrants (think: Burning Man, but poor) that blows your mind around every twist and turn and stabs you in the heart more than once. My capsule from The Film Stage’s Best Cinematography of the Year: Move over Dune(s), there’s a new desert movie to mark the decade. DP Mauro Herce’s gritty, tenacious visual aesthetic is so comparatively desolate (there is no “spice” equivalent, much less water or hope, for that matter, in the deserts of Southern Morocco) that it renders Arrakis the less grim and godforsaken setting. Oscillating between deep, purpley blues, golden hour oranges, and unsaturated daylight brights, Herce’s cinematography––and sixth sense for framing dusty music equipment against arid landscapes––lends the devastating adventure a propulsion that simply can’t be unfelt once it’s all said and done.