Dailies is a round-up of essential film writing, news bits, and other highlights from our colleagues across the Internet — and, occasionally, our own writers. If you’d like to submit a piece for consideration, get in touch with us in the comments below or on Twitter at @TheFilmStage.

Amazon has picked up the exclusive rights to stream Drafthouse films releases, Lost Remote reports.

At Nonfics, Daniel Walber highlights the best documentaries on LGBT history and culture:

Once again, Happy Pride Month! Last week we featured a list of the 10 Best Documentary Portraits of LGBT Culture, films that celebrate the lives and loves of their diverse subjects. Today’s list is entitled “The Best Documentaries About LGBT History.” What’s the difference?

The distinction is, in a word, politics. Obviously when dealing with something like LGBT civil rights, culture and politics are often very closely connected. Yet the following 10 films are more consciously political, narratives of the struggle for freedom and equality over the course of history. It might be a misnomer to call all of them “activist” documentaries, and the “issue film” moniker seems reductive.

Therefore, we’ll call them history films, built from a century-long struggle against discrimination. They feature the earliest days of the Gay Liberation movement in the United States, the fight to respond to the AIDS epidemic, and the international scope of the pursuit LGBT civil rights around the world today.

YouTube is now serving up videos at 60 frames per second, Gizmodo reports.

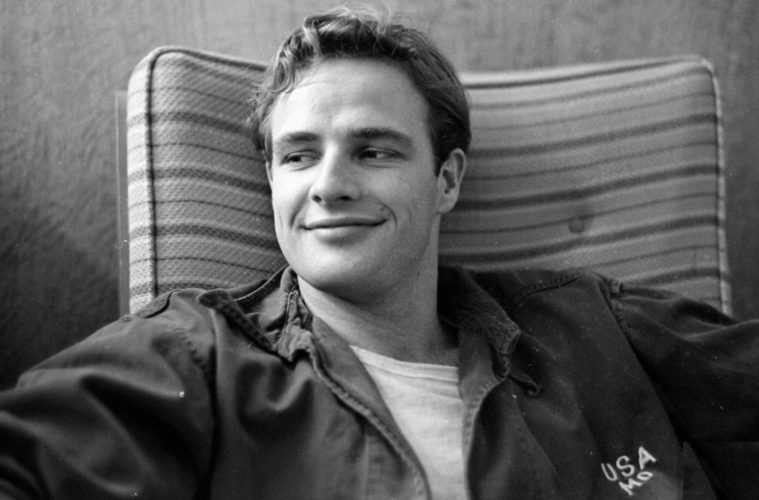

At The Atlantic, Tom Shone on how Marlon Brando broke the movies:

Hollywood extracted entirely the wrong moral from the story of Marlon Brando. Working when the studio-contract system crumbled in the 1950s, he quickly leveraged the power he had accrued from his theatrical performances into a series of one-picture deals, allowing him to exercise unprecedented freedom in selecting roles. Straight out of the gate, he played a paraplegic (in The Men, 1950), a Polish factory salesman (A Streetcar Named Desire, 1951), a Mexican revolutionary (Viva Zapata!, 1952), a Roman general (Julius Caesar, 1953), and a biker (The Wild One, 1953)—a remarkable, radar-jamming zigzag across the field that left the star system looking as fixed and faded as the stars once painted onto the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. That zigzag is now standard course for the modern movie-star changeling, flattered for “disappearing” into roles by everyone—studio heads, casting agents, publicists, magazine writers, even critics—except the general public, which gives no sign that its conception of the stars has moved an inch. Instead, chameleonism has become its own form of marquee spectacle: come see the stars transform. We don’t go to the movies anymore to be convinced. We go to be tricked—to admire acting as a kind of special effect. Watching Christian Bale, with a bloated belly and a thick Brooklyn accent, flop around in a comb-over in American Hustle, we must, for the performance to succeed, at the same time hold in our minds the idea of Christian Bale as we know him: a handsome Englishman who has also portrayed Bruce Wayne. As with trompe l’oeil, the trick must work but not work, simultaneously.

The Academy has invited Claire Denis, Olivier Assayas, Chantal Akerman, Thomas Vinterberg, and more to become members, and changed their Oscar rules.