Happy End is a perplexing title for a movie by Michael Haneke, a filmmaker not exactly known for his irony whose endings have ranged from the death of all the central characters via murder and/or suicide (this has happened on four occasions) to the inception of Nazism. Lest anyone should suspect the redoubtable Austrian of growing soft, before the opening credits of Happy End have even finished rolling, a twelve-year-old has already killed her hamster and poisoned her mom, all of which she records and sarcastically comments on with a Snapchat-like app.

The girl is Eve Laurent (Fantine Harduin) and after these fun exploits she moves in with her father, Thomas (Mathieu Kassovitz), who abandoned Eve and her mother several years prior and now lives with his new wife and child in the opulent Laurent manor together with the rest of the clan. The Laurents are quite the package: Thomas is not only a negligent father but also a consummate adulterer, his father Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant) is senile and suicidal, his nephew Pierre (Franz Rogowski) is an alcoholic with crippling mommy issues, and his sister Anne (Isabelle Huppert), the de facto matriarch, runs both the household and the family’s construction company with oblivious self-interest.

Happy End’s prologue, depicting atrocities committed and filmed by a teenager, suggests that we’re in store for a new Benny’s Video updated for the age of social media. The film actually turns out to be an amalgamation of concerns from across Haneke’s oeuvre, something that is signaled through an accumulation of references to his earlier work: Georges at one point tells Eve that he euthanized his wife in the same manner Trintignant’s character does in Amour; the extremely sexually explicit online correspondence between Thomas and his lover harks back to the letter written by the protagonist of The Piano Teacher; the way the presence of the Laurents’ Moroccan servants puts the family’s privilege in stark perspective is strongly reminiscent of Code Unknown; and so forth.

Surprisingly, considering Happy End feels like a summation for the director, it’s also his most restrained work – and his flattest. The violence is kept at a simmering level throughout, only boiling over on one or two minor occasions, and while the characters are generally objectionable, they’re not particularly compelling. Rather than follow a concrete plot, the film presents a relatively loose collection of scenes that gradually reveal each of the Laurents’ self-destructive egocentrism. A major issue is that the characterizations don’t reach very deep and in the absence of a robust context or involving narrative, it’s actually the references to Haneke’s previous films that flesh out what is otherwise a rather perfunctory condemnation of the bourgeoisie equipped with the usual symbolic connotations.

Haneke depicts the bourgeoisie as a class afflicted by terminal cancer, not only gestating its own demise but also infecting everything it comes in contact with. Its eventual death is presumably the happy end referred to in the film’s title. As such, it is deferred for the moment, though Haneke promises that when we do finally go under – because there’s no mistaking who it is he’s pointing at – we’ll be the directors of our fate as well as its spectators.

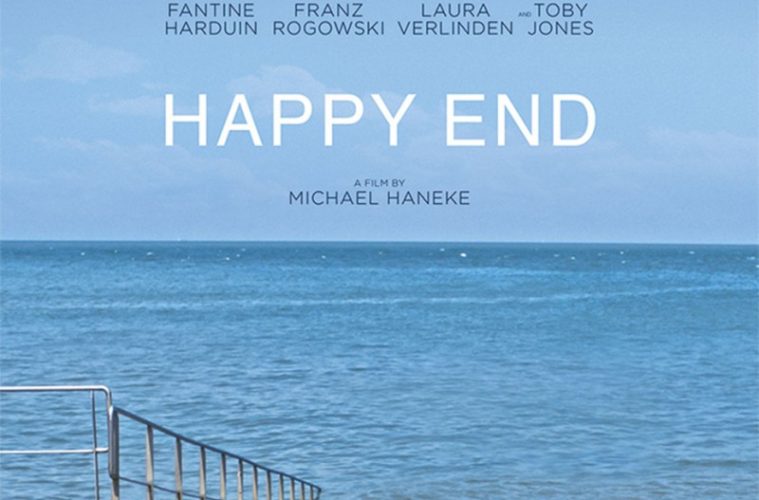

Happy End premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and opens on December 25. See our coverage below.