It is either my gift or my curse — maybe both; how you end up feeling about this piece will do a lot to decide — that I have been tasked with assessing one of the Brian De Palma films towards which few feel any need to express a strong, set opinion. (The director offered this ringing assessment in Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow’s documentary: “You know, it wouldn’t necessarily be your first choice.”) “Be your own man!” you might say, which is just the thing: for as much as I enjoy his 1978 telekinesis-espionage actioner The Fury, and no matter the fact that I consider a handful of its sequences some of the very best in his oeuvre, the thing can take a bit of time to get there. But there exists a chance — a fine chance, in fact — that we may extract from its stop-start, hot-cold rhythm a further case for De Palma’s brilliance.

Let’s first take that insufferable auteurist’s route and lay a good deal of blame at the feet of screenwriter John Farris, who adapts his 1976 novel in such a way as to make me hope I’ll never have to read it. Almost every piece of dialogue in The Fury’s first sequence is a sign of what’s to come from his end: thrown-together locations (“the states”; “Chicago”; “a good school for you”) and more-than-clear intimations of characters’ relationships with one another (“since Mom died”; “give up soccer?”) in an attempt to stay above an expository fray. Yet something in the way of intrigue nevertheless emerges — a notice from father to son that this young man possesses “a talent that will shock the hell out of people.” Andrew Stevens as Robin, the son of Kirk Douglas‘ Peter Sandza, can groove with the dialogue just fine, and while the latter and John Cassavetes are too magnetic a pairing to be handed standard-issue conversations that see “a couple of guys” ribbing each other in an affectionate manner, preternatural talents make them strong enough to sell it to a certain point.

And at least they have De Palma. The extent to which he might have whipped all this into a stirring cinematic experience is more a matter of taste, but the how and why of his involvement with this material is a bit less disputable to even a semi-familiar eye. Nearly every exemplary piece of this sequence is a product of a director and cinematographer (Richard H. Kline) who manage to trace the effects of conversational rhythm through particular patterns. As if engineered to spice up bland material, the camera accomplishes its own effects by slowly oscillating between father and son in a ground-laying sequence; without cutting, it then settles on a locked two shot of Douglas and Cassavetes, the latter of whom has replaced Stevens in conversation, and in this formal schema are the picture’s most charismatic actors trusted with delivering the most “naturalistic” dialogue. (Make of it what you will that I still use quotation marks.)

Curiously enough for a supernatural film by a director whose name is most often associated with spectacle, both lovingly and derisively, De Palma’s main characteristic here is great restraint — or, some would just say, patience. Perhaps, after digging myself than 500 words in, I should tell you The Fury is more or less his version of an X-Men story, tracking a young man, Robin (Stevens), and woman, Gillian (Amy Irving), who possess what can only be described as “intense psychic powers.” The description’s left to only those three words because the film is at once rather blunt and largely vague about what, exactly, these people might be capable of. The closest point of understanding is when Farris’ script piles on a few dialogues about new age-sounding concepts and scientific possibility, which register as ineffectively from the actors as they do De Palma — who, with Kline, most often photographs actors in close-ups and two shots when they aren’t engaged in some sort of psychic, physical, or conversational show-down. (That is to say, when they’re explaining.) If it’s worth nothing that he feels more lost (or simply detached) here than in almost any other film, it should especially be said, perhaps in part to distract blame (there’s that auteurist route again!), that even Douglas and Cassavetes only bring marginal life to what’s on the page.

More than granting The Fury’s standout sequences a sense of relief, it makes them all the more delightful, no matter that they’d ring stellar with or without surrounding material of just about any quality. It’s in this film where De Palma latches onto something that I’m not sure he’s ever really expanded upon, or at least not done so well: representations of human thought under moments of extreme duress and attention alike. It’d seem he’s having the most fun with portraying psychic abilities, but the visual trait that stands strongest — mastery of the extended take, no doubt a reason many even see his movies — does so because it’s played in an ostensibly simpler register. It’s not just that he’s doing something well; it’s that he’s doing something even style-over-substance detractors should (should) recognize.

Consider the page-to-screen transition of a scene in which Douglas’ Peter Sandza, a man on the run and seeking his kidnapped son, is discovered by and introduces himself to the tenants of an apartment, who he’ll have to hold hostage for his safety and some clothes. It’s an extended dialogue sequence that only (speaking literally) brings him into the picture halfway through — and, given the situation and exchange between players, one that would most likely be depicted as a series of wide, medium, and close-up shots. De Palma stations a camera at a point between the apartment’s living room and entrance hallway, oscillates between separate spaces, sets a clear midpoint for the image (the patriarch of this shabby home standing in fear of an unknown occupant), and makes necessary revelations through well-timed pans, performers’ onscreen entries as dictated by dialogue, and focus-racking. It’s as much a matter of efficient staging — something every director should know, not something they should really be congratulated for — as anything else, but in comparison to, oh, 95% of ways it otherwise would have been handled, it’s as revelatory as it is effective in a present moment; and when compared to The Fury‘s worst scenes, where De Palma is contained to a particularly confined setting (e.g. cars and buses) and a few expository pages, it at least feels as out-there as whatever would typically go into a career-highlighting montage.

Being that these films are separated by but two years, it’s hardly surprising that The Fury‘s visualization of psychic powers resembles Carrie in many a regard. These are easy to imagine — close-ups of faces in thought, quick cuts to a moving object, a screech on the soundtrack, a quick zoom communicating mental action — so it’s the differences that mostly compel. Here’s what I consider key to appreciating this as a unique work: The Fury is more upfront about its properties than Carrie, embracing them in a fuller, more giddy, and sometimes more perverse way. The Fury’s opening action sequence — a failure on De Palma’s part, more mechanically assembled image-by-image than cut together for maximum effect — contains a shot from a cameraman’s POV. In the moment, this induced a smile for “allowing me to recognize” an “indulgence” on the meta-textual De Palma’s part. What it does later is far more surprising: serve as the bedrock of a sequence wherein Irving’s Gillian envisions a group communicating information to her. A static close-up of the actress’ face alternates with a projection of her mind that rather resembles a live-television-director’s studio, the camera panning wildly from multi-television display to multi-television display until firmly settling — focusing — upon a screen playing the footage from earlier, in this barely stable state of intensity amply generating the thrill of a shocking cinematic image.

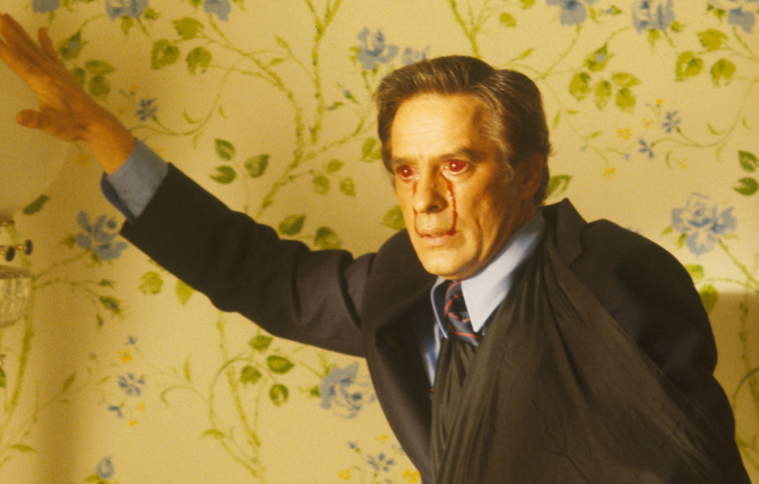

It is these supernatural expressions that so profoundly affords The Fury the “shocking” label, one more apt than just about any other De Palma film. With the likes of makeup master Rick Baker at his side, he compounds the oddity of these indescribable strengths with very real expressions of pain through a series of inflictions that seem to mount encounter-by-encounter, from an authentic-looking, mentally transmitted nosebleed to a woman who, with the touch of Gillian’s hand, begins convulsing as she oozes blood from every visible orifice to a bizarre, carnival-side comic set piece that seems horrifying but ends on a weirdly innocuous note to a tortuous, Carrie-esque, blood-spattered killing to, finally and of course, the sight of John Cassavetes being blown the fuck up not one, not two, but thirteen times in what Pauline Kael somewhat implied is cinema’s greatest climax — and a fine climax for De Palma, who embraces standard continuity editing at long last, albeit as a means of instilling comfort before his final, disorientingly cut jolt of an explosive encounter.

Let’s end, then, with a terribly concerned moral question: does the artist enjoy this pain a bit too much? For me, the primary pleasure of Brian De Palma’s cinema is what pleasure he seems to take from building these worlds of glances, gestures, attacks, pain, ecstasy, roving cameras, voyeuristic POVs, and split diopters, and it’s with this appreciation in mind that I acknowledge some hard-to-ignore discomfort with The Fury’s casualty rate, or perhaps just its means of racking up casualties. (Sue me for being sensitive. The thought of profusely bleeding from every fingernail is hard to shake.) Yet the formalist’s playground it so often affords him, despite (and sometimes because) he’s bumping against lesser material, is its own source of joy — a conduit for what I tend to enjoy most in the first place. And isn’t indulgence the feeling his filmography, best and worst entries alike, serves better than just about any other?

Continue reading our career-spanning retrospective, The Summer of De Palma, below.