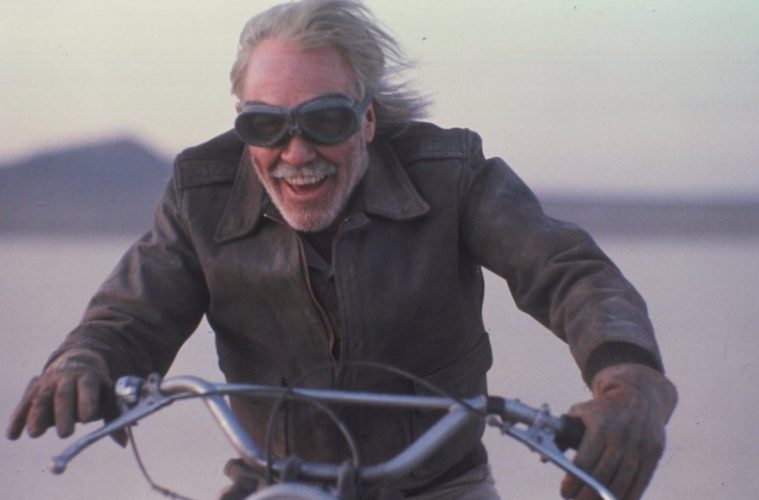

Melvin Dummar (Paul Le Mat) is a gambler of sorts, but that is intrinsic to the life of a lower-middle class American. He lives in a trailer, has an estranged wife (Mary Steenburgen, in an Oscar-winning performance), and drives a beaten-up truck whose paint job can only be described as “dirt on rust.” He’s the living epitome of a country music song where a man works 9 to 5 every day only to come home and scratch off lottery tickets in the dream of living in a more prosperous genre of music. Melvin is a bit of a singer as well, and prides himself on his Christmas jingle that he’s sure is going to be a hit someday, cutely titled “Santa’s Souped-up Sleigh.” Melvin debuts the song to a haggard crypt-keeper of a man (Jason Robards) he picked up off the road. Melvin infectiously sings the song, insisting that this tattered old man join in on the fun and he eventually wins him over. The magic of Christmas, one could suppose. That man would later be revealed as none other than eccentric billionaire Howard Hughes and Melvin’s act of kindness, both in carrying a conversation with the man and bringing him to Las Vegas, bore the seeds of Hughes as he includes a bad luck-stricken Melvin in his last will and testament. But who could ever believe Howard Hughes would’ve made time for someone as average as Melvin?

Melvin Dummar is a Rosetta Stone figure for Jonathan Demme’s conception of America. There are eccentric characters spread throughout his filmography, like the mafia goons in Married to the Mob, but for the most part Demme was interested in real salt of the earth people. He has a fondness for characters who have slipped through the cracks to one degree or another, like the politically conservative failed rocker mom, Ricki (Meryl Streep), or Melanie Griffith as a spontaneous, frenzied, fashion forward woman who can’t stand still, because she’s running from her past. Demme’s best films are about women, but all of his films are about America. Melvin Dummar is a dreamer, someone who believes a better life is attainable because he’s a good person. Demme’s history of being a Good Samaritan and something of a cinematic saint bring to light a kind of self-reflexive criticism where Dummar can be seen as a stand in for Demme. He’s man with music in his bones and a kind-hearted streak that outweighs both his intelligence and his bank account. He’s the kind of guy who would get chewed up and spit out in corporate America, but corporate America is for the birds. The soul of the country, at its best, is in people living their life to the fullest, chasing their dreams or living them.

The inherent tragedy of it all is that a chase is all Melvin Dummar’s story ever is, and he has to fight hard to prove he knew Howard Hughes. It all circles back to the fact that earlier in the film Melvin and his first wife Lynda lucked their way into being a game show, but blew all the money before they could even blink. The futility in the economics of the American middle class is that when gifted the chance to shovel yourself out of the shit, life has a way of dumping it right back on top of you. That this doesn’t seem to break Melvin Dummar speaks greatly of his character and his guile towards setting an example for his family that he can be more than a dreamer, but someone of substance. Melvin eventually loses his wife when he proves he couldn’t become the sort of man she expected. He remains a compulsive spender with a sympathetic demeanor. It’s hard to hate Melvin Dummar even when he lets you down. He has a puppy dog quality that resists classifying him with contempt when he frustrates and fails to really move forward. He’s stunted in a way, but more so because of his inhibitions toward a better life overpowering his day-to-day state.

The greatest strength of Melvin and Howard is that despite the tragedy of Melvin Dummar’s almost-riches, the film sustains a warm, doughy quality that casts these unfortunate prisoners of America’s ruthless capitalism as sympathetic through their imagination. The grass may not actually be greener on the other side, but in Demme’s America, one doesn’t need to feel ashamed for imagining what it might be like after all.

Melvin and Howard is playing at BAMCinematek on August 13 as part of their series Jonathan Demme: Heart of Gold.