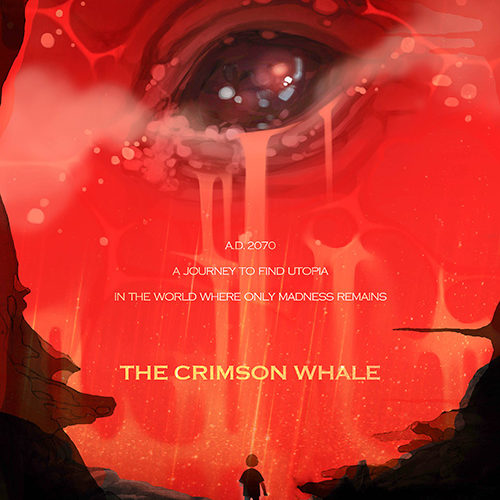

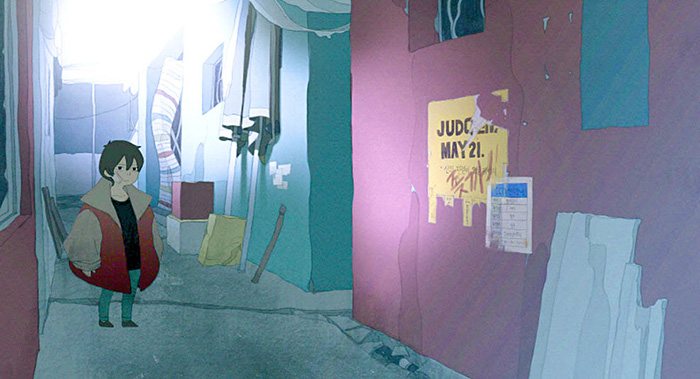

A product of the Korean Academy of Film Arts’ Advanced Program, writer/director Park Hye-mi‘s Crimson Whale is a fascinating little sci-fi adventure. The hand-drawn character design is cutesy with young faces and oversized clothing dwarfing stature, but the 2070 Busan in which they reside is brutally dilapidated. Looking at young Ha-Jin or even older, bumbling explosives expert Lee carries presumptions that this might be a kid’s film, but that’s definitely not the case once the first f-bomb is delivered. Just because it’s a cartoon with an orphan girl at its center shouldn’t diminish the message Park brings concerning revenge, survival, and the maturity to know one from the other. After all, this earthquake and volcanic ash riddled future hides dark enough secrets to make a crazy expedition of killing a monster the best avenue towards salvation.

Ha-Jin proves a well-drawn heroine at its center: a not-yet teen girl who spends her day selling drugs to idiots before stealing their money after they’ve passed out from the high. Nightmares keep her awake at night with memories of her mother and a pod of whales ravaged by dog and human teeth alike. It’s a part of her life that exists only within her subconscious now, one she’d like to forget despite strangers arriving out of the blue to recruit her specifically because of that past. They tell Ha-Jin of an island left unscathed from the carnage, one that can be bought for the right price. If she goes with them to Taal Volcano to lure out the titular Crimson Whale, they can kill it and take its treasure of Uncentium to retire from their thieving lives.

We will eventually learn of what happened to Ha-Jin and understand the reasons she trusts no one at their word. Skepticism aside, however, staying in Busan while children are being scooped up and sold to sailors to work slave labor at sea isn’t an alternative she should seek to embrace. These pirates—led by a one-armed Captain who lost her limb to the beast she hopes to vanquish—ultimately kidnap her/save her depending on whose version of the story you take and begin their journey to the volcano. If Ha-Jin can use her talent of speaking to marine mammals, Lee can set off his charges while Tenjin and Andra harpoon it through its blowhole. Some of them want revenge like their Captain while others merely want the booty. Ha-Jin, on-the-other-hand hopes to find a family in their friendship.

The first half in post-apocalyptic South Korea possesses a nice streak of humor from the juxtaposition of this little girl against the adult junkies and corrupt police officers she must engage with daily. Nothing is better than her turning on the waterworks when arrested—snot running down her nose—in order to simply be let go. Her temper doesn’t do any favors in the long run, however, and those taking the brunt of it do find their frustration hard to ignore before beating on her like they would anyone else. But this is what she’s used to and exactly why she’s cultivated the chip on her shoulder to answer with an “I didn’t ask for your help” where a “Thank you” is appropriate. So when the Captain offers a choice to join their mission, such respect is unfamiliar.

The second half at sea is full of comic moments too, but it’s the more horrific imagery of the deformed whale and the harrowing experience attempting to kill it that stick out above the rest. Park pulls no punches as far as the stakes and her homage to Moby Dick brings with it ample casualties as the truth of who each member of the party is reveals itself. They’ve all participated for selfish reasons—even Ha-Jin—and it becomes a question of whether seeing the monster first-hand will stoke the fire within or wake them up to the futility of their desire. Some can’t see past their rage, willingly putting their lives at risk to see the whale fall to its death. Others simply watch as those they care for perish.

It’s a powerful climax delivering quality science fiction themes like sacrifice and hubris. The characters are three-dimensional despite stereotyped occupations—young Ian serving as guide even has deeper seeded motivations alongside his brother Tenjin and their history with the creature. What occurs is mostly to open Ha-Jin’s eyes to accept what she did long ago, but that isn’t the whole story. Crimson Whale‘s biggest strength besides the fantastic backdrop/environment art is that we feel for these characters: their youthful vigor and well-beyond-their-years pain. The world’s thrown into chaos and the whale’s both a metaphor for their struggle to survive it and the literal wall blocking their path towards freedom. Like in real life, though, that freedom comes at a cost. And when things are this bad, even death can be considered a consolation prize.

Crimson Whale is currently playing at the 2015 Fantasia International Film Festival.