Following The Film Stage’s collective top 50 films of 2025, as part of our year-end coverage, our contributors are sharing their personal top 10 lists.

10. The Navigator: A Medieval Odyssey (Vincent Ward, 1988)

It’s not common, once one has consumed a few thousand movies in one’s lifetime, to come across something so strange, so alien, that it actually feels like an artifact from another world. Vincent Ward’s cracked 80s fantasy adventure has recognizable reference points, to be clear: the premise, of medieval English peasants stumbling through a time portal to 1980s New Zealand, would seem to suggest the absurd hijinks of Terry Gilliam or Queen-scored camp of Highlander, but Ward audaciously plays it with an obsessive medievalism and somber post-Christian yearning more suggestive of Bergman or Tarkovsky with the epic chops of Ridley Scott. The historical setting immediately imposes its otherness on the modern viewer with meticulously authentic costumes, sets, dialects, music, and even superstitious ways of seeing the world: the protagonists act on what they believe are visions sent to a prophetic boy by Jesus, which the film’s audiovisually operatic tones frame as being just about as serious and real as the characters believe it to be. When they arrive in “our” world for a divinely heralded quest, the script flips, and modernity — streetlights, highways, televisions, submarines — is framed to be as inscrutable, awe-inspiring and terrifying as it would seem to farmers and craftsmen from six centuries past. This works — or at least is impossible to forget — because Ward evidences himself as a man who has truly, deeply thought about how a 1300s metalworker would process, intellectually and emotionally, a contemporary roadside auto body shop and the blokes who work there; it’s a Deep Thought pondered so intensely that it smashes through silliness and back into profundity, charting a course of vast ethnic and cultural memory to reconcile the past and present, looking at the miracles and menaces of modernity with wide eyes turned upward. And it’s also a brisk and thrilling adventure film, so there’s that too.

9. Notre Musique (Jean-Luc Godard, 2004)

I’ve never been ashamed to admit that Godard’s early work does little for me, his groundbreaking formal innovations striking me as largely academic, married to a snooty mix of obscure irony and didacticism which (again, to me) speaks more to a precious hipsterdom than intellectual refinement. So I’m more surprised than anyone that Notre Musique, his solemn and visually beautiful meditation on conflict, peace and lost dreams of utopia at the dawn of the 21st century, haunted me in the way it did. The content of the film is complex — a Dante-inspired triptych that opens on the “hell” of historical atrocities, captured and recreated on film, and characterizes the present day as “purgatory”, a dense, elusive series of images and dialogues with a loose narrative thread about a Sarajevo-set international peace conference, covering topics as diverse as film theory, semiotics, colonialism, the Bosnian War and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. But the reason it works is simple: it’s Godard at his most open-hearted and uncertain, a prayer for peace that admits it does not know what peace is or where precisely it might be found in a world so shaped by violence.

Chantal Akerman caused a minor splash back in the day by accusing the film and Godard of antisemitism. She wasn’t exactly wrong: Godard goes beyond political criticism of Israel (of which there is plenty) to make broad and, let’s say, contestable claims about the significance and character of “the Jew” as symbolic category first and ethnographic reality second, one which he places in existential opposition to “the Palestinian”. This is before dropping a climax in which the world is saved by the beautiful, guilt-ridden Jewish protagonist (Belgian actress Nade Dieu) becoming symbolically Christian. Yet this critique is complicated by the film’s deep weaving of self-contradiction into its own dialectical structure; numerous critiques of, say, oversimplification of the Other voiced by various speakers in the film could seemingly be applied to the film itself, and Godard, essentially fulfilling two very different roles behind and in front of the camera, is as often inclined to pensive ambiguity in the former role as fiery didacticism in the latter. “Truth has two faces,” declares the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish in a showstopping monologue, and indeed, the film is a cinematic catalog of dyads and contradictions — art and violence, peace and war, East and West, European and indigenous, analog and digital, documentary and fiction — that combine into paradoxes, adding up to the dizzying double consciousness of an examined life in the postmodern century. Binaries, borders, and even shot/reverse shot editing are, Godard argues, not sufficient to describe a world of so many perspectives and such a contradictory species. His film is antisemitic and philosemitic, parochial and inclusive, patronizing and humble, religious and secular, hopeful and despairing, sentimental and intellectual, beautiful and terrible, sophistic and profound. It’s, ironically, European thought in a nutshell — the very object of its critique and concern. It’s Godard at a point where he had figured out how to transpose his entire messy, probing consciousness and array of found cinematic objects into mesmerizing poetry, and perhaps his most earnest example of such.

8. The Driver (Walter Hill, 1978)

Speaking of purgatory! People in The Driver’s nocturnal capitalist afterworld don’t have names; they have verbs, and if they verb hard enough, superlatives. That’s not figurative speech: the film’s Process-obsessive characters literally have no names, only job titles (The Driver, The Detective, The Player, etc.), and each pushes themselves to the amoral limits striving to be the Best Damn [X] in the Biz. It’s the kind of ruthless, garrote-tight minimalism that would be almost too affected on the page, but onscreen — where a scenery-chewing Bruce Dern can chuck verbal daggers at an ice-cold Ryan O’Neal (with Isabelle Adjani snaking in between) during 90 delirious, cut-to-the-bone minutes of cops-and-robbers mind games, GOATed car chases, and nonstop hustle — it soars. (It’s a testament to first-rate editing and some truly fearless stuntmen that this makes us completely buy Mr. O’Neal’s titular thug as the most hyper-competent bullet of a man ever unloaded into the streets of LA.) It’s pulp fiction with the stylings of Hemingway, and for neo-noir historians a vital evolutionary link between Jean-Pierre Melville and Michael Mann — not to mention Quentin Tarantino, James Cameron, Edgar Wright, and (most unabashedly of all) Nicolas Winding Refn. It’s a film of diamond-cut design that speaks for itself so fully that to sit around describing it almost feels like an insult. Better to hop in and take the ride yourself.

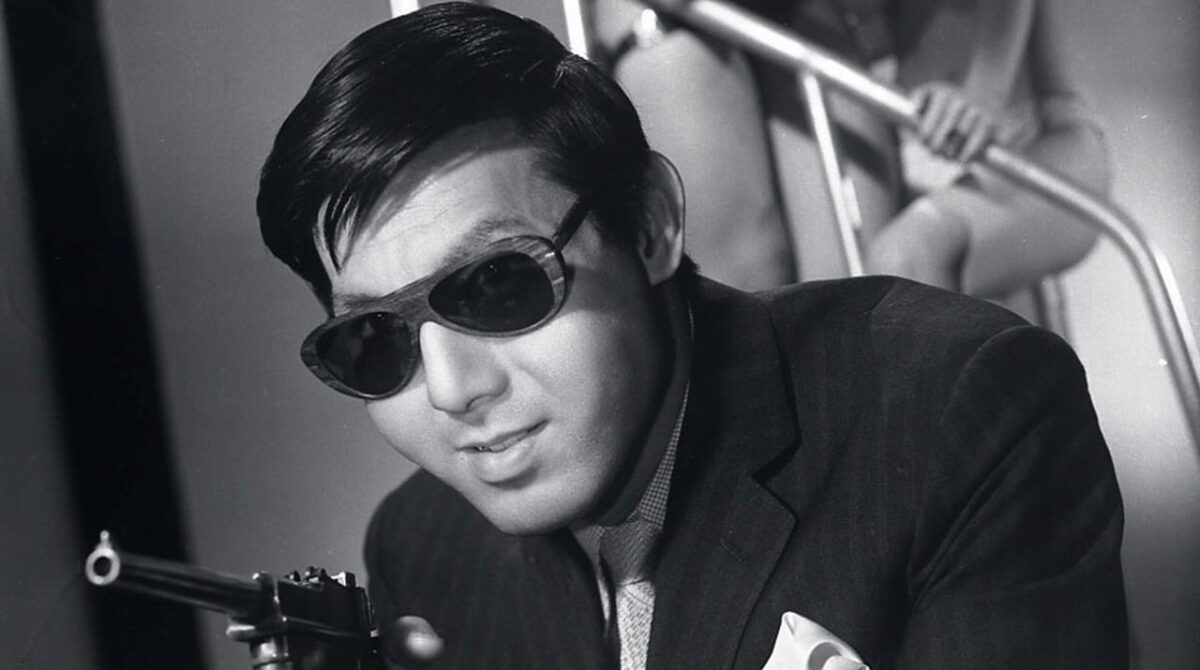

7. Branded to Kill (Seijun Suzuki, 1967)

Another quietly influential neo-noir milestone and generational touchstone of cool, but operating on a very different track from Walter Hill. Suzuki’s opus checks every box of a beautifully efficient, silicone-slick noir exercise — a tragicomic opera of machismo and desire, a stark piece of urban expressionism filmed in tight angles and inky chiaroscuro — but with one key distinction: the plot, typically such a key feature of the genre, operates on pure Dada dream logic. Assassins in salaryman suits play a Calvinball-type deathmatch game and get into shootouts choreographed like playground paintball matches to prove they’re the best; femme fatales bluntly describe a fetish for death as their allegiances shift on a whim. The characters take their Looney Tunes contests of violence deathly seriously no matter how little sense they make, compelling the audience to become a little bit looney themselves just to meet the film on its wavelength — just like modern society, am I right?

Star Joe Shishido, with his squeezable chipmunk cheeks and indoor shades, is effectively sold in the film’s first act as the coolest man in Japan, a quirky fashion-forward lone wolf determined to slay his way to the title of #1 killer in the inscrutable Little League of hired murder. By the end of the film, he’s turned into a sweaty voice-cracking mess and we’ve seen enough of his kinks, fuckups and sexual misadventures to recognize in the very affectations of style-savvy grit that initially wowed us the desperate performances of a poseur, a man pigeonholed into an absurd, atomized existence from which he eagerly bars his own escape. It’s both a perfect distillation and scathing critique of the noir-style study in masculinity, bringing all the genre’s entangled sex and death drives starkly to the surface by kicking the support structure of narrative realism out from underneath it. It’s also, per Suzuki norm, a dazzling experiment in form, maniacally cut (twenty minutes in this feels like you’ve already seen half a movie) and seemingly inventing never-before-seen camera setups out of wholecloth on the fly, just for the hell of it: for just one example, a rising circular pan around bright water in a dark shower, all to reveal Shishido making frenzied love to his macabre mistress in the background, remains — as far as I’m aware — unreplicated.

Once you’ve seen it, the film’s enduring imprint on the cinephilic gene pool becomes impossible to miss: its grotesque yet ultra-stylish spectacles of arbitrary violence following arbitrary rules have informed everything from Chan-wook Park’s murderous social satires to Goichi “Suda51” Suda’s baroquely self-aware violent video games. And yes, Tarantino and Refn are noted fans too. None of this diminishes the mach-speed-escalator momentum of the original gangster, whose unique production circumstances — a contracted sleaze pic descended upon by starving experimental artists, “punched up” to the extreme in sarcastic contempt of the studio — are impossible to replicate by intent. The film is an engraved bullet fired straight from the unconscious.

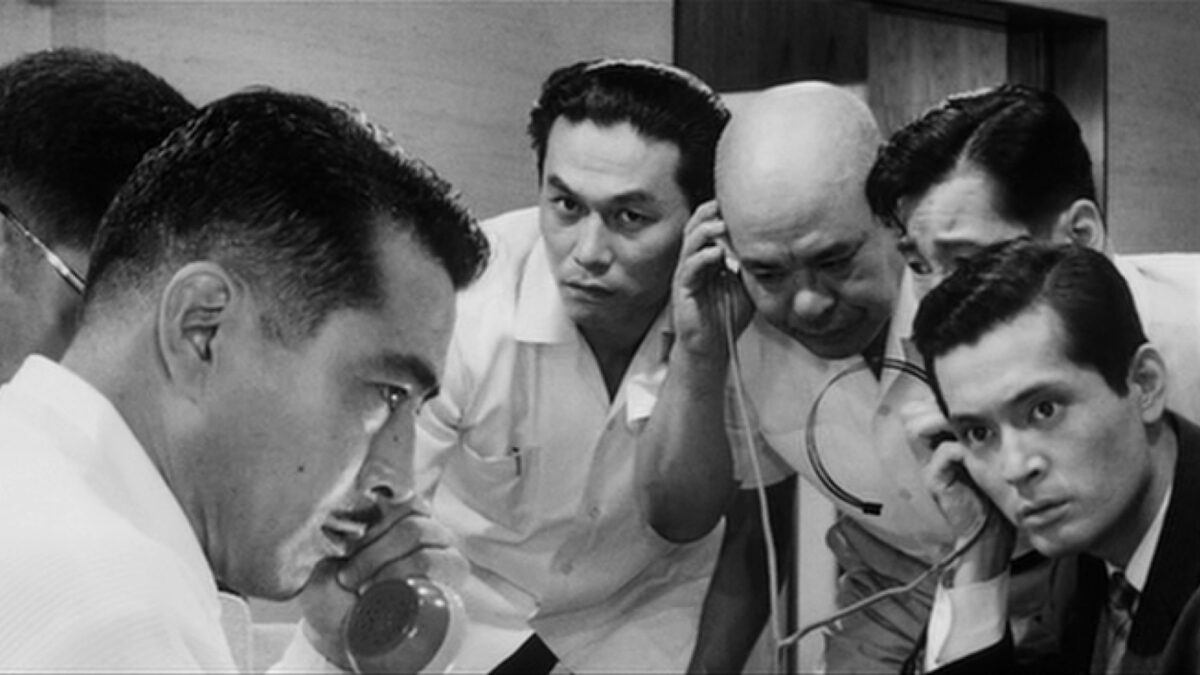

6. High and Low (Akira Kurosawa, 1963)

A vision of postwar Japan as honor-deprived urban battleground every bit as stately and grownup as Branded to Kill is incorrigibly punk. Thank you to Spike Lee for pulling this one up from less-discussed Kurosawa to a film with more Letterboxd loggings than Yojimbo and The Hidden Fortress. I, too, was guilty of sleeping on it: I find Kurosawa films to be almost too perfect, masterworks of composed form so purposeful and rational as to give film educators endless teaching material while brooking little audience debate about their efficacy and meaning. That’s true of High and Low as well, so forgive me if my appreciation for the film sounds a little passive-aggressive — did you know the title refers all at once to the high physical placement, social status and moral self-conception of a business executive in a high-rise suite, contrasted with the lowness of a working-class criminal in the slums? Or that the entire film (opposite Notre Musique!) is ingeniously structured as a Dante-adjacent three-part descent (Japanese title: Heaven and Hell) that transforms its own style and subgenre twice over, from ultra-composed chamber drama to multi-threaded criminal justice procedural to grimy, jittery chase thriller? It’s all so perfect, an ostensible genre riff that casually bends genre to its will for the sake of a socially conscious modern literary text, deeply married to its form, its commentary on the enduring inequities of a society where capitalists have replaced warriors at once layered and unmistakable. If I taught a film class I would put on High and Low every semester, possibly even demand students watch it twice, just to teach the essentials of blocking, framing, theme and structure, what genre is and when to obey, subvert or creatively repurpose its norms. Would I put it on for fun, though? Ahhh… maybe.

5. Triumph of the Will (Leni Riefenstahl, 1935)

The shot is a montage, endless profiles of chiseled young faces gazing upward, forward. The reverse shot is the camera drifting slowly along the packed seats of the amphitheater, fixed upon the podium, bobbing slightly, inhabiting one perspective after another after another, uniting all as one. The establishing shots are the towering overheads of a thousand bodies moving in sync, like the blood cells of one great body, flowing through a medieval city filled with shining new structures, spaces where immemorial generations of European tradition meet a bold, angular and unstoppable modernity. Every time his opening act declares that He Is the Nation, as he is about to ascend the podium to deliver a fiery gospel and, bathed in radiance and towering over the masses, look quite divine, we get an intimate backstage shot of der pensive Fuhrer gulping silently, anxiously. Riefenstahl takes great care to show us. He is human, you see, after all… and at the same time, like Christ, a conduit for something greater… he is the Nation… and the Nation is all of you!

There seems to be a revisionist movement in some film appreciation circles, after decades of canonization in college film courses, to declare Triumph of the Will a cinematic sham, a film undeserving of attention both because it is evil and because it is “boring.” These people are wrong: in 90 years there has never been a more necessary time to take Riefenstahl’s art seriously. If you seriously can’t appreciate the primate appeal and deft ego-destruction rituals that Triumph is laying down, you’re either too disconnected from human beings as political animals for me to trust your judgment on politics (and too uncomprehending of fascism to oppose it effectively) or not enough of a visual thinker for me to trust your judgment on cinema. Every socialist filmmaker, from Vertov and Eisenstein with their intellectual montage theories to Godard with his diatribes against shot-reverse shot editing, has argued their work to be the first step in awakening a new collective consciousness; of all the propaganda films I’ve seen, only Riefenstahl’s has made me truly feel like a part of one. Like the ideology it so cohesively embodies, her work offers a twisted yet visceral parody of socialism with a narcotic appeal, a too-good-to-be-true offer to the alienated capitalist subject to end their lonely emasculation and assimilate into a proud, virile collective; this collective made all the more appealing by embodying not merely the intellectual weight of History and Science but the nostalgic warmth of Blood and Tradition. Experience this film’s hypnotic ebbs and flows of symmetry, slogan and spectacle, its calculated deployment of buildup, repetition, exhaustion and release to cloud the mind and erode the individual’s sense of self, and come to understand better than any documentation of Nazi crimes can reveal what spell of the mind drove its adherents not just to kill and die for die Nation, but to exterminate the masses of the unworthy. When people are not individuals but cells in a greater being, the need to protectively expunge cancerous cells and enact the people’s will upon rival beings comes to seem natural, and in fact selfless in the most absolute and literal sense.

Triumph of the Will, examined earnestly as an art object, is a testament to the instinctual power of cinema and an instructive marriage of form and ideology. It is of course profoundly, cosmically evil, and evil in a way that can only be confronted head-on, looking both outward and inward. To understand that fascism’s big lie is so deeply romantic, that it is, in the hands of an artist like Riefenstahl, entirely compatible with aesthetic beauty and catharsis, is to disabuse oneself of silly fantasies about the intrinsically liberating spirit of art or the natural alignment of moral and aesthetic truths. To understand Triumph of the Will, to allow oneself to feel it, is to understand not only the heart of the enemy but one’s own capacity for temptation. It will, in all likelihood, always be relevant.

4. The Trial (Orson Welles, 1962)

The forever boy genius of Hollywood, rarely a man to withhold public assessments of his own output unto the world, declared upon completing his Kafka adaptation that it was his finest film to date. (Correct me if I’m wrong, but I’m pretty sure he successively updated this claim for every film he worked on thereafter.) Seeing it on the big screen, you can appreciate that he may have at least had a solid argument. Combining the ego-crushing brutalist behemoths of postwar East European architecture, the hostile, hysterical modernist sets and lighting of his Broadway days, the jagged, claustrophobic compositions and cuts of his shoestring-budget Othello, Welles crafts a singular (and, once again, singularly influential) vision of dystopia as an industrial dreamscape where “rational” rules beget nonsensical behavior and every structure and system is aligned against the individual. Certain creative interpretations and additions to Kafka’s text, like an absurdly overextended, featureless stage filled with endless desk workers on typewriters, or the inclusion of a giant computer to which management types eagerly surrender their decision-making processes, bring the story seamlessly into the then-present moment while suggesting, not for the first time, that the wunderkind may have had the gift of prophecy.

Add all this together and you have one of the most sensually striking anti-authoritarian parables in cinema (give or take an original ending perhaps a bit too sentimental for the material). But, Welles being Welles, it is also an inward-looking psychodrama about ego that coyly tempts metatextual readings as an auteur confessional. It’s impossible not to think of Welles’s now-infamous verbal evisceration of Woody Allen as The Trial ruthlessly prods Anthony Perkins’ hyper-neurotic and petulant Josef K, constantly exposing the emasculated worker drone’s cowardice, myopia and concealed self-importance for the audience’s derision even as it fully indulges his self-centered suspicion that the whole world is, in fact, out to get him for no real reason. Welles diabolically reinterprets Kafka’s Jewish-coded paranoia as queer concealment, weaponizing Perkins’ closeted homosexuality as the essential “something to hide”, making him squirm as a procession of sexually aggressive vixens throw themselves at him incomprehensibly. (Far from objecting, Perkins described working with Welles as the high point of his career.) And while the film paints K’s neurotic self-doubt (and possible closetedness) with such empathetic texture as to make it nigh-impossible to believe there’s nothing personal in there – a certain type of man is all but guaranteed at least a few moments of cringe-inducing self-recognition in Perkins’ anxious thought processes and social faceplants – Welles himself appears in the film playing the part of the crooked lawyer Hastler, a haughty tyrant who relishes his gilded name and ability to direct others’ lives, can seemingly have any woman or material pleasure he wants, and takes to humiliating his clients purely as an assertion of his own draconian ego.

Thus Welles orchestrates the opportunity to bully covert narcissists from behind and in front of the camera, while both mocking and flaunting the image of the imperious Orson Welles held by his detractors, and in all this dares the audience to ask if the Great Man in fact sees himself in the cowardly wretch he’s tormenting. It’s needlessly indulgent, painfully clever, helpfully illustrates how the extremes of low and high ego form a horseshoe, and it’s the kind of flex that only the mischievous, ego-obsessed Welles, a precocious adolescent from the cradle to the grave, could have added to an already outstandingly weird and perversely funny literary adaptation.

3. Happiness (Todd Solondz, 1999)

Dusty gulps, throat-clearings, and smacks of the tongue; stuttered half-syllables that fail to produce words; at times, the glopping and squelching of bodily fluids. These lovingly rendered details of Happiness’s rich foley (the title Misery was taken) are just as often scene-stealers as the lethally precise faux-inarticulate dialogue, which tends to fall along a binary of characters on their respective bungled journeys to happiness either spectacularly failing to express themselves or expressing themselves in more detail than their audience ever desired. Solondz’s controversy-baiting cult classic reigns supreme over both the hardcore cringe comedy and “repressed desires in whitebread suburbia” prestige ensemble fiction genres (compare reception for American Beauty, released the following year) which were such major strains of American cinema for grownups in the 90s and 00s. Its genius lies in crossing those strains, hammering with extreme and imaginative violence into the ironic comedy of audience discomfort zones while exhibiting a profound and complex empathy for America’s freaks and losers — the productive friction of these two modes notoriously exemplified by its deep dive into the disturbed mind of a pedophile (Dylan Baker, terrifying for his confident normieness), prodding audiences to both laugh at and relate to scenarios they never would have dared to consider such responses to.

This all might make Happiness sound like an edgy endurance test, but it really is a film so immaculately funny that pain becomes pleasure. Every performance and character in the ensemble, from the indie heavyweights (PS Hoffman as an unbearably shy pervert, Jane Adams as a dazed and directionless failed creative, Ben Gazzara as an unwilling alte kaker, etc.) to the bit players and child actors, is hyper-specifically caricatured to the point of that they feel like real people we once knew in passing, now taxidermied and blown up under a magnifying glass before us in the most masterfully ridiculous and lavishly ugly dioramas.

Solondz has real literary concerns too, but is too militantly unpretentious not to excuse himself from didacticism. The film’s most cartoonishly skewered character is a successful author (played by Lara Flynn Boyle) who yearns to relate to “losers” and fetishizes misery as “authenticity”, actively looking to become traumatized so she can write about it. Solondz himself clearly has a lot of thoughts about misery and authenticity, but he’s unwilling to be reductive: the film diagnoses an urgent crisis of people not living and connecting authentically, but also questions the limits of “authenticity” as a pursuit. Repression isn’t good, but what if people “living their truth” and expressing their “authentic selves” unfiltered is dangerous, unproductive, or simply blasé? Would the world really be a better place for extensive access to our inner monologues? Are we ourselves reliable judges of who our “authentic selves” even are? Solondz’s willingness to truly put himself on the level of his characters, no matter how low, before asking such questions open-endedly (if skeptically) is what most distinguishes him from his many more condescending peers in the field of American middle-class values critique. (A preternatural talent for casting, pacing, constructing scenes and landing anxious laugh lines certainly helps.)

I’m sorry I’m late to the party: Happiness is a canonical document of American life at the semi-privileged margins, and one of our great nation’s best films of the 90s.

2. Talking Head (Mamoru Oshii, 1992)

I’ve known I was an Oshii-head since Ghost in the Shell (films 1 and 2) captivated me in high school. But one of the highlights of 2025 for me, as preparation for my all-too-brief interview and pieces on Angel’s Egg and The Red Spectacles, was diving into my many blind spots in his back catalog to discover just how little about the great sage of anime I actually knew. The surprise revelation for me was, by far, his surreal satirical live-action film about anime and filmmaking – a widely neglected footnote in the Oshii catalog whose reputation among fans of his more iconic sci-fi and fantasy productions is mostly just, “it’s weird.” Well, it is weird, but it’s also one of the best and funniest metafilms I’ve ever seen – no small praise, because I usually find filmmaking to be one of the most banal subjects possible for a film.

Describing Talking Head in a nutshell isn’t easy, but Oshii starts from a simple joke: that directing a film within the strictures of a commercial system (and it doesn’t get much more commercial than anime) is akin to running a criminal operation. This is hardly a novel metaphor (though it was perhaps a bit more so in 1992); but whereas other commercial postmodernists like Mamet or Tarantino would make a glib crime film about sassy criminals dropping filmmaking double entendres, Oshii shoots a deconstructive film on a Brechtian stage that is literally about anime production, yet frames it all with the deadpan conviction of a dreamlike, discursive noir that fits right in with his genre catalog. Oshii’s wiry kabuki-clown leading man Shigeru Chiba hams up a tough-talking journeyman director hired, in the back of a limo in a foggy neon haze, to take over a blockbuster theatrical anime production from an absentee auteur. (The premise of the gun-for-hire commercial filmmaker as sketchy fixer noir protagonist, by the way, feels so fitting and obvious that I’m astonished I haven’t seen it elsewhere.) Attempting to wrangle the wayward production, he sets about interviewing the creative staff (all bizarre Alice in Wonderland-esque parodies of Oshii’s colleagues, like a spoof of screenwriter Kazunori Ito who can pluck off his own “talking head”) on their contributions and conflicting visions for the film. Each contributor – actors, colorists, sound mixers, editors, etc. – makes an elaborate argument, carefully situated in aesthetic philosophy, film history, and practical illustrations, for why their craft is the most essential element of the film; to this the director must push back and, eventually, synthesize the contributors’ distinct perspectives into the whole. But complications arise when a metafictional serial killer, seemingly escaped from the scenario of the film-within-the-film, begins picking off the staff; in trying to solve the mystery, please the studio financiers and complete the film all at once, the mercenary director is increasingly torn between the forces of art and commerce.

Even this description barely scratches the surface of this wildly dense and multilayered mindbender, where genre pastiche provides formal and emotional cover for Oshii to stage a series of complex dialectics on film theory, editorializing freely about the filmmaking process in hardboiled drag. Relative to his obvious touchpoints in Fellini, Godard and late-period Welles, Oshii leverages his unique experience working in both animation and live action, and on both big commercial projects and avant-garde indie productions, to offer wholly unique thoughts on the texture and identity of the cinematic image, the repressive structures and norms of “the industry”, and the successful filmmaker’s necessary split personalities of romantic artist and cynical hustler. It’s all very obviously autobiographical, but Oshii is less interested in auteur self-mythologization than in picking apart the medium(s) he works in and his personal and professional relationships with them, down to the very strands of their intellectual DNA. (In fact, the lack of authorial ego on display is remarkable for the metafilm genre – Oshii shows intense interest in the contributions of his cast and crew, and his self-insert protagonist, initially introduced as a punchclock hack, is ultimately defined not by his maverick personality or preternatural genius but by his commitment to the project.) The minimalist soundstage sets and expressionistic images, bathed in eerie crimson light as if under a blood moon, strewn with visual reminders of cinema’s past and scored to the ever-trancelike music of Kenji Kawai, evoke the animation studio as dream factory with extra-literal emphasis on both the “dream” and the “factory”: a harsh, cramped industrial space where gangsters call the shots and also a site of transcendent wonder and horror, a gathering place for strange and beautiful madmen (and women) in which dreams are born, killed, and linger on as ghosts to possess future generations. An obsessive love and bitter, jaded resentment for animation and cinema are in constant struggle throughout, and while it’s as exhaustive an onscreen statement of intent as any filmmaker has ever offered for their own craft, it’s also not too self-important to let loose and have fun – as when a creative conflict between director and animator is resolved via spectacular John Woo-style shootout laced with Duck Amuck-style hijinks – or even to make fun of its own indulgences, as when the film-within-the-film’s producer grouses about “all this deconstruction, metafiction, postmodern stuff.”

Like his idol Godard, Oshii’s sometimes-narrative, sometimes-essay film suggests that filmmakers require a sort of schizophrenia, an ability to occupy two spaces and hold two contradictory thoughts in mind at once, to make art in a capitalist system and postmodern world. Such holy madness defines the career of one of Japan’s most undervalued auteurs, and makes of Talking Head an impish prank hiding a singularly rich and challenging work in the director’s corpus. With the recent 4K restoration of The Red Spectacles, Oshii’s first live-action feature, here’s hoping for similar treatment and renewed availability for a film about filmmaking which, perhaps more than any other in the last four decades, deserves to sit in regular critical conversation with the New Wave classics of the form.

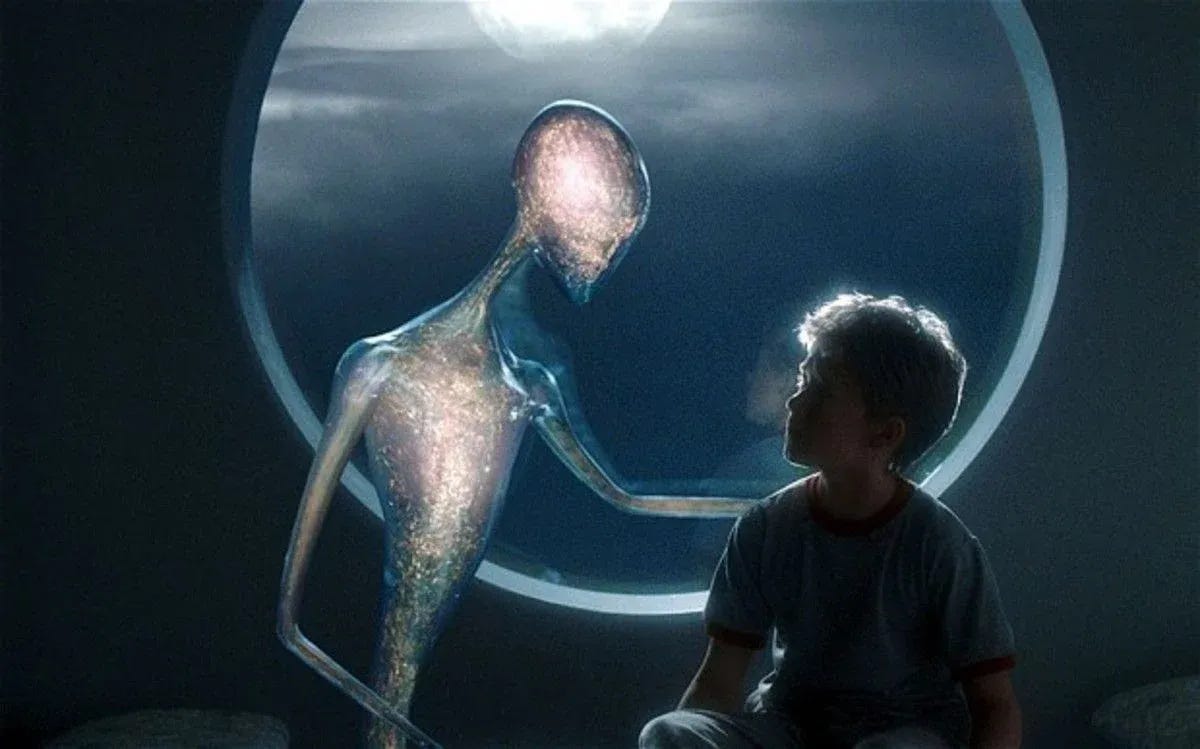

1. AI: Artificial Intelligence (Steven Spielberg, 2001)

Hard to know what to add to the conversation about a film that’s been so influentially and eloquently championed since its release (and right up to the almost-present moment) by living legend Jonathan Rosenbaum.

Here goes nothing.

AI was on my “milestone list” of movies for years. These are movies I anticipate and fear seeing for the first time so much, I cannot bear to lose my virginity to them until I know the moment is right. For instance: I still to this day haven’t seen Barton Fink, even though the Coen brothers are among my favorite filmmakers, because the Coen brothers are among my favorite filmmakers, and once I’ve seen Barton Fink there will be no more new old Coen brothers movies to discover. Often these milestone-potential movies are the last, among the last, or the only one of something. Thinking a couple forks in the road ahead, I suspect that, having finally laid eyes on them, I will have permanently closed a gate dividing “life experiences I am yet to have” from “life experiences I have had”. Watching each one will also be the opening of a gate, the objects on the other side of which are now just visible enough in silhouetted contours to stoke my fantasies, but not enough to know for sure if they are solid or mirage. To reach out and touch them could, depending on the texture of the object and my state of mind in touching it, result in a pleasure on par with holy ecstasy or a disappointment to send me tumbling into despair. That’s how sensitive my skin is, and it’s sensitive because I keep it carefully covered up, because I don’t want to lose what’s left of that capacity for sensation. And whether tactile, visual or purely psychological, a truism here is (mostly) true: you only get one first impression.

Films are synchronized sequences of images and (usually) sound. Films are hard data. They can be encoded into objects and mass produced, or they can be encoded into digits and made infinitely reproducible. They are signals, patterns, and automatic imprints, a finite number of frames that can be analyzed, deconstructed, and fabricated down to the last one. They are pinned-up tapestries, to be admired for the pleasingness of their patterns and the density of their weaving. They are friendly chess matches, intellectual dialogues with an author, in which each party tries to read and anticipate the other. They are jigsaw puzzle scavenger hunts, a game of looking for shapely pieces someone clever left behind, finding those pieces’ place in a big picture that no one player ever fully completes.

But films are also not that at all. Films are the memories of having watched them. Films are the person you were and the place you were in and the people you were with when you watched them. They are the first face you turned to or the first person you messaged to talk about them after the credits rolled. They are both the path and the destination. They are your journey as you besotted yourself with the sights and sounds of the path, as you felt your mind alight at the sensations of the moment, dizzily adrift in the possibilities of what can come next. They are the arrivals, the eurekas, the flashes of light when puzzle pieces connected; they are the unique and fleeting solution you found when you ran them through the codex of every sight you’ve seen and sound you’ve heard and daydream you’ve dreamt and person you’ve known right up to one exact moment; they are the way your perspective on the great unsolvable puzzle shifted even the tiniest bit in that moment, the way gravity dropped out for a split second as your view changed.

Repeat visits may yield new paths, pieces, strategies, and solutions. If the film is truly great, they will do so every time, even as the rate of yield starts to slow, even as certain wings of the journey start to feel automatic, reflexive, as the roads start to wear down with use, as faces and words slip into patterns and signals, as experiences slip into copies of experiences. Great films grow older and wiser with you, but in a core way you will always understand them by reference to that one first journey together. Your mind is a cavernous space in which all notes become echoes, and the echoes fade but rarely go away; even if you try to re-hear the note, the instrument and the echo will now overlap, and you will end up hearing a different and busier sound entirely, no matter if you discover a richer harmony (rare, and lucky) or only wish it could be as clear and sharp as the first time.

Is that enough metaphors? The point is AI – a film about the difference between copies and originals and between life and data that asks, among many other questions, whether emotions induced by fiction are “real” or simulated – was perched atop some lofty expectations for me. Steven Spielberg and Stanley Kubrick were two formative voices in cultivating my love of film, and two filmmakers I make no apologies for loving to this day; big-ticket mythological science fiction, done right, is one of my most beloved types of movie. Emphasis on “done right.” Spielberg and Kubrick’s sensibilities, both brilliant, are also so vastly far apart, almost diametrically opposed – sincerity versus irony, motion versus stillness, individual versus system, sentiment versus intellect, optimism versus cynicism – that even just the idea of combining them, i.e. AI’s major pitch to cinephiles, felt… odd. And indeed, AI has the reputation of being a polarizing oddity, with a common consensus that the ghost of Kubrick sits uncomfortably and imperfectly in the shell of Spielberg.

This year I covered the New York Film Festival. It was the first time, in all this time, that I had both the opportunity and courage to attend a multi-day event surrounded by people/Twitterers whose knowledge and appreciation of film could make me look like the biggest poser in the tri-state area. I think I managed to not make a complete fool of myself. (Thank you to Odie Henderson especially, if you’re somehow reading this, for treating me like I was interesting.) The best films I saw during that week weren’t the actual festival selections, but the restored classics at the Metrograph that I ran off to see every open night. I caught an original 35mm print of AI the one time it was playing, the same evening I would later realize I had also caught Covid-19. (If anyone who attended a Metrograph screening of AI: Artificial Intelligence on the first of October came down with Covid-19: I am truly, deeply sorry.)

It was worth it. It was worth saving my first time for the big screen and the hum of the city. Hell, it was worth getting sick as a dog for half of October. That’s how mind-expanding it felt to watch AI for the first time on real film in a real, non-simulated theater.

It turns out everything they say about it is true. And not true. A dead director possessing a live one. Two distinct and very different voices, sometimes clashing, sometimes harmonizing, and sometimes producing a sound you can’t even classify beyond the deep discomfort it instills.

AI is absolutely a part of Kubrick’s body of work, and in many ways a more fitting capstone than Eyes Wide Shut: a direct culmination of his thoughts on consciousness, humanity, modernity, and technology that brings them to their farthest conclusions at both the micro and macro scale. It touches on Dr. Strangelove’s witlessly self-inflicted technological doomsday, 2001’s pondering of “intelligence” and its potential non/post-human manifestations, A Clockwork Orange’s fear of a postmodern society desacralizing the body and mind, The Shining’s corruption of the nuclear family and intimation of historic horrors waiting to recur, Eyes Wide Shut’s weighing of sex and love as biological puppet strings and transactional commodities, even what we might assume to be the unproduced Aryan Papers’ child’s-eye view of the Holocaust as directly downstream of industrial modernity – each of these revisited strains twisted in a meaningfully new way and woven together toward a totalizing (yet tantalizingly ambiguous), bleakly absurd (or absurdly bleak) conclusion. All throughout is the distinctly Kubrickian view of humanity: as myopic, irrational, tragicomic brutes, with an awe-inspiring spirit of invention yet ultimately defined by their base desires, doomed to one day be overtaken by their own beautiful and frightening creations.

Yet it is indelibly Spielberg as well: Kubrick would never with such abandon have framed a bourgeois American suburban home as soft-golden-hued Garden of Eden in quite the way Spielberg does, nor directed such disarming and heartwrenching performances of uncanny, not-quite-human innocence as Spielberg coaxes out of lead androids Haley Joel Osment and Jude Law. (Osment’s performance in particular is among the most breathtakingly nuanced in the history of child leads, and his favorite role to this day for good reason.) Kubrick certainly wouldn’t have had John Williams tearing into our emotions with aching piano melodies and haunting futuristic lullabies in already devastating scenes (though, per Kubrick’s request, there is one marvelous needle drop of Strauss’s “Rosenkavalier” incorporated into an original piece). It is far and away the most fucked up of Spielberg’s fables about trials of faith and parental abandonment – which is really saying something! – yet it slots in comfortably alongside the full gamut of his work from E.T. to Schindler’s List. Spielberg’s humanism crossed with Kubrick’s sighing, chuckling misanthropy means that no character is without sin and selfishness, yet none is fully denied sympathy, leading to one of the film’s most incisive observations: that all of its characters’ cruelest acts stem from a mortal fear of being discarded and replaced, emotionally, socially or economically, in a world where all that is human is objectified and any object or experience can be replicated. His perpetually searching, naive view of cruel and incomprehensible realities renders the icy modernism of Kubrick with a lurid, hot pain that Kubrick could never have wrought. (It must be highlighted that a film conceived as hi-tech Pinocchio also happens to offer one of the most eerily, enduringly plausible prophecies of decline in the history of dark Hollywood futures: accelerating climate disaster and socioeconomic disparity in an isolated America where technocrats are gods; roving bands of conservative populists, people in search of a paycheck, or just plain sadists rounding up an entrenched underclass of “disposables”, created for exploitable labor, to subject them to grotesquely commercialized public spectacles of torture and erasure. Brendan Gleeson’s briefly seen but memorably spit-flecked demagogue all but shouts, “You will not replace us!”)

What seals the film’s greatness more than anything else is its profoundly twisted Freudian fairytale ending, the one so widely misread that some still falsely accuse Spielberg of tacking it onto Kubrick’s story. In fact it’s the most breathtaking harmonization of the two men’s visions in the entire film, one which plays out like the titanic and intimate final passages of 2001 and Empire of the Sun, not combined but multiplied by one another: at once bitterly ironic and utterly sincere, a dance of matter and souls, obliteration and recreation, transcendence and oblivion, selfishness and love, restored innocence and childhood’s end, a universe that is cold and empty and yet so so full, a twining of two thoughts we struggle to madness to hold at once in our heads all our lives and the lives of all our civilizations. It breaks people, rightfully, and I had the immense privilege of seeing it break a half-full theater of grown adults. (And yeah… me too.) That’s the objectively correct way to enjoy your first time with this movie.

Two contradictory thoughts, again, held in mind in the face of meaning’s death. Not just an embrace of uncertainty; a tactical insanity that makes it possible to move, feel, and create in a world that seems to be trapped in deadly entropy. That’s what love is, I guess, and faith as well. It’s my moviegoing lesson of 2025, entirely by accident.

Thanks for reading.