Writer/director/star Catherine Eaton’s feature directorial debut The Sounding is finally available nationwide digitally after a planned theatrical run was unfortunately scrapped due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s been a long time coming considering we reviewed it in 2017 out of the Buffalo International Film Festival, but even longer for its creator considering the one-woman theatrical show that spawned it, “Corsetless,” hit stages in 2007.

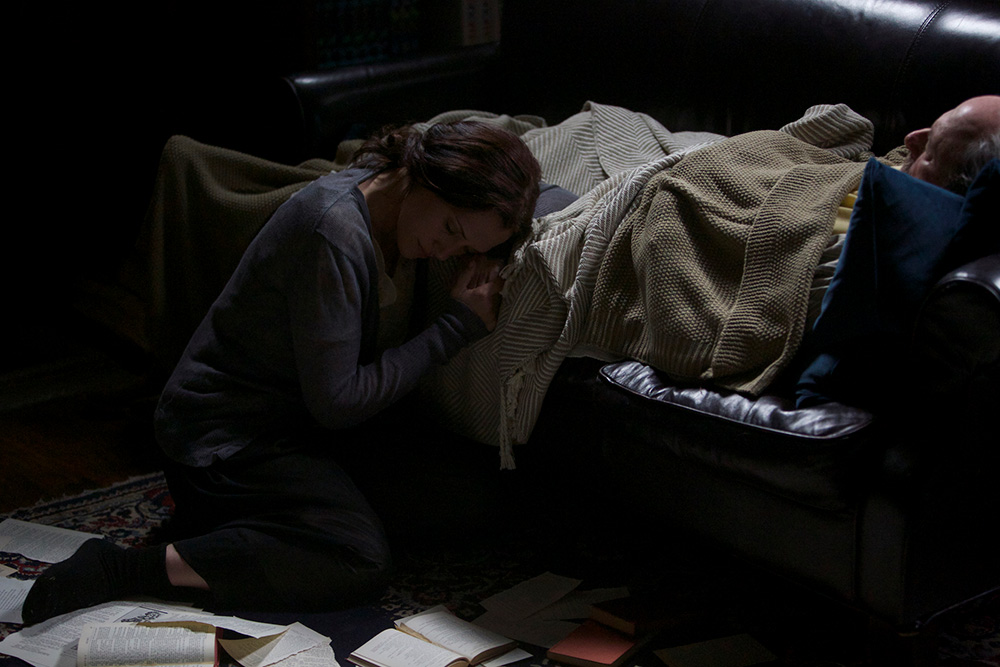

The film is a timely story about “otherness” and society’s desire to want to assimilate rather than accept. Eaton stars as a woman named Olivia who is introduced as a completely non-verbal (oral or written) person living with her grandfather on a tight-knit island off of Maine before tragedy forces her to speak … but only through the words of William Shakespeare. The result is an emotionally and philosophically touching piece that highlights the complexity of marginalization and seeks to find clarity in the notion that being different does not intrinsically mean being a threat.

We had the pleasure of speaking to Eaton about the years-long journey she took transferring this character from stage to screen, her writing process to integrate the Bard into her dialogue, and the sanctity of using one’s voice boldly.

The Film Stage: We’re now three years past when I first caught The Sounding—and it’s almost depressing to say—but its themes of “otherness” and isolation might be even more relevant now. How does it feel to be releasing the film now with everything it’s saying against this backdrop?

Catherine Eaton: Yeah. The film stands as a testament to living boldly when someone puts you in a box—in this case quite literally. I think that that, on a very simple level, is something many of us can relate to through our experience during the pandemic and what that has meant for people both physically and also emotionally in terms of living your entire life online and not being able to be in contact with other human beings. So there’s something that’s really spoken to there in a way that I hope is life-affirming and ultimately joyous, but is a struggle. The thing I keep likening Liv’s journey to is a “personal revolution.”

Initially the film was conceived, of course before the pandemic, about “otherness”—an extreme form of “otherness” in this case, but that’s really a stand-in for any of us who have felt marginalized for one reason or another and have felt an oppression as a result of that or a desire to rebel against that. I was really curious about what happens as we live our lives and make choices that aren’t accepted by society. What happens then? Sometimes we’re marginalized for things we can’t control and sometimes we’re marginalized for decisions we make and how we live our lives. So what happens when we make that decision and hold firmly to it?

Is it society’s responsibility to protect us or take care of us? Or is it—my personal belief—to allow us freedom to live that choice? Or is it society’s responsibility to take care of society and protect the structures that make society work? And what are those structures? Those are kind of the more heady ideas, but really, on a very essential level, I think the film is about pushing forward the freedoms of people who are marginalized. I hope that Liv’s voice—literally—helps people to find and stand up for their own voices. That’s what I would love for this.

The film didn’t originate from those bigger ideas. It originated from more personal questions and this character that kind of came whole to me. But then you start to explore who that character is and how they live and what that life means and then these things come from that.

In that vein: it’s been three years since the film hit the festival circuit, but this has been a much longer journey for you starting on the stage and moving towards a short before the feature. What was that evolution like?

It’s been a journey! [Laughter]

It’s been really extraordinary, actually. I have the best job in the world. For all its incredible ups and downs it’s a gift to have the chance to live with this story that I love and was spawned completely from my imagination. I have the blessing to work with so many incredible collaborators who are just as committed to this—in this case the final piece of work. But to each step along the way were just committed to the creative process and the world and to the character as I was. And that’s just humbling and inspiring and exciting.

Then to also bring it through these different forms and stages: the theater piece was incredibly different from the film. I mean really, really, really different. It had its own crazy life with incredible stories and the festival experience was just an utter joy. That’s really the chance for a lot of independent filmmakers to meet the audience in a way that we don’t maybe get to at this stage as directly, right? Because it’s going out widely on VOD and on digital platforms, so I don’t get to sit in the audience with human beings and watch them respond and hear them ask questions afterwards.

We played to a thousand people during one screening in Stony Brook and had three sold-out screenings in Istanbul where people waited four hours afterwards to ask questions because they found it incredibly relevant to the political atmosphere in Turkey and this sort of cry for rebellion and revolt. It happened to be the same week—I believe—when women were banned from performing on-stage again. So the festival experience was a gift meeting people and hearing their thoughts and seeing how this light and sound you throw up against a wall is resonating and living in people’s imaginations after they leave the theater and cinema.

Now I get to share it with so many people who didn’t get to see it yet who have been with me along the way. They’ve been asking about it and looking for it. So it’s a real gift. It’s been incredible.

The press notes talk about that “crazy life” of the theater piece. Could you elaborate on that?

I wrote this one-woman show [“Corsetless”] and it went all over the place. It went to Carnegie Hall. It played Irish Classical Theatre in Buffalo. It went to the UK. All over the place.

I was invited to do it at this glassed-in storefront space that is a part of the Roger Smith Hotel in Manhattan, which is on 47th and Lexington. I had been doing this series of artist salons up in the penthouse rooms where the hotel had generously donated the space to me to bring artists that were friends for no charge and with no audience to share work in process. So I had been doing that and sharing pieces of the play while I was working on it in the salon and the artistic director of the hotel—which they had because the owner is a sculptor—said, “I think you should do this in our performance art space downstairs. And I said, “No.”

After a year—we’d become very close friends—he wore me down and said, “Why are you in New York if you’re not going to do crazy, wonderful things?” And I had to agree. So I brought the director of the play, Derek Campbell, who’s an incredible stage director, in to re-direct it for this space. We made it into this hyper-modern isolation room in a psychiatric hospital and inside was a woman in a gown scrawled with Shakespeare, spouting Shakespeare. And it became this kind of cult hit.

The sound gets piped out onto the street and hundreds upon hundreds of people walk by every day. The sidewalks became packed and the police had to come because it became a fire hazard. The cars would stop in the intersection and wouldn’t keep moving. Stockbrokers would come and stand under the phone booths and talk on their phones saying, “There’s this crazy woman shouting Shakespeare in this glass box.” Parents with kids. There was a homeless man that lived somewhere nearby who would come and bang on the glass and say, “I’ll get you out! I’ll get you out!”

And every night this man would come in a tuxedo that I thought was a caterer because I didn’t know anyone else who would wear a tuxedo every day. He would sometimes come alone and sometimes with his family and he always had a peach colored Financial Times under his arm, so the guys in the back jokingly called him “the Financier.” They’d say, “Oh. Has the Financier come tonight?”

On the last night of the play he waited for me afterwards and said, “I want to turn your play into a feature film.” He became the first investor and literally changed my life. I had no aspiration to direct. It never occurred to me that I could. I had never worked with a female director before at that point—in theater I had, but never on-screen.

For both of us it was a big journey from that moment until we both understood what it meant. He supports the arts, but he’d never invested in a film before. And I had never made one. [Laughter] So it was that journey that took me to this point.

So does that mean it was your initial intent to find someone else to direct? When did you decide that you would take the helm yourself?

To be honest, initially I sort of thought: Does he mean archivally? To film the stage-play? So there was a lot of translation needed and he didn’t really know. He knew that the character of Liv resonated with him and he wanted her to have a bigger audience, a bigger platform. The story of her “personal revolution” was still a mystery and he wanted to make that happen. So we slowly went through the process of figuring out what that meant.

Then I was lucky enough to have incredible producers come on board and other investors. During that time we thought we would find a different director. I hadn’t even thought to direct at all. As we went through the process of talking to agencies and looking for the right director, I would talk more and more about what it needed to look like visually and how I felt it needed a subjective camera. And at a certain point, not too far into that process, the producers and investors came together to me and said, “We think you should direct the film. We think you have the vision for the film and no one will ever know this story better than you do because you’ve embodied it. And we think you have what it takes to do it.”

I sat on it for a minute. Went home and talked to my partner (playwright and co-writer of The Sounding, Bryan Delaney) and he said, “You’re crazy if you don’t say yes to this!” And he was right. So I said, “Yes.” And I’m so grateful and have never looked back.

What was the casting process like after that? I know Frankie Faison was also in the short film version, but also getting someone like Harris Yulin to deliver such a wonderful turn as Olivia’s grandfather.

They’re incredible. The talent and my crew were just amazing.

Frankie is fantastic. I’m a huge fan and we’re very good friends now. We had actually done a show together because I came up as an actor professionally before directing. Now I try and do both—sometimes together, like this. Frankie and I had done a show together called “Reparation” and had become friends. He heard about the project and was wonderful and said, “I really want to be a part of it. Is there something for me? How can I support you?”

When I did the short—which at the time I already knew the feature was happening. I had this kind of reverse blessing that a lot of directors don’t have: we had investors for the feature. I did the short as a way of—and we never released it—teaching myself, putting myself through a lab as a director and also seeing if I could direct and act and do I have a point of view as a director and do I like directing? What did it mean for me? Because I had never done it before and it was the most rewarding experience I had ever had. So I knew I had to do it after that.

So Frankie was kind enough and generous enough to be in that and then played his role again on a bigger scale in the feature.

Harris I did not know. Harris Yulin is a gift to us all. He is an extraordinary talent and human being. We went out directly on offer to him. I knew his work and I loved it and he was one of the first people I thought of for the role of Lionel. We went on offer to him through the casting director’s office and he graciously accepted it. He read the script and that’s what sold him on it. He said, “I have to do it and I want to do it.” And he’s classically trained.

Then he said, “Now I want to meet her. Now that I’ve said yes to this role, I need to meet her.” So he invited me to go and watch a production of a Shakespeare play that he directed at Julliard. Which is sort of, you know, am I going to be able to hold up in the conversation afterwards? I watched the production and it was outstanding. And then I met him for tea afterwards and he generously grilled me about Shakespeare and the film. We ended up staying for six hours. He had friends coming for dinner and invited me to join them and from that point forward I would lay down in traffic for him. He’s just an extraordinary human. I feel very lucky that he graced us in coming on-board.

And he really was a gift on set as well because someone with that history and legacy behind him can really set the tone—for better and worse on any film set. He was so committed to the project, to me as the director, to receiving my direction. He puts pressure on things when he has questions and made sure every word in the script mattered to him. But I love that. That’s exactly who I want to work with. Every actor who came on-board was really incredible—all extremely different in the way that they work. Some of whom I knew before and some I didn’t.

Speaking of Shakespeare: the logistics of what you’ve done is mind-boggling. Using his words to sometimes serve as one side of an entire argument like in the climactic scene between Olivia and Teddy Sears’ Michael—and yet you do it in a way where they always become her words. What was your process in writing the script and finding the right passages to re-contextualize through her voice?

Yeah. We call that scene “the battle.” The “Shakespeare Battle.”

In terms of how to work with the language, I had performed a lot of Shakespeare’s plays as an actor because I came up classically trained also. So I had a lot of it in me. And I love it. It is something I’m passionate about.

So it kind of worked a few different ways. Sometimes I would be searching for something that needed to be said and the language would come up from my memory and my experiences with Shakespeare. Sometimes I just loved a quote or a piece of Shakespeare and I knew that I needed to include it and wanted to find a way to do that. There are a few nods to that: like the “Henry V” speech, the “We few, we happy few, we band of brothers” speech is in there because I love it and have always wanted to deliver it and have never been given the opportunity because it’s a male role. Which, fortunately, there are all-female productions now.

And then sometimes I’d also go searching through the canon or Bryan or I—because I wrote the play on my own, but Bryan and I wrote the screenplay together and it was a massive undertaking with an enormous amount of change. So a lot of the Shakespeare I use in the play got thrown out and we went searching for new things. In that case we would sometimes think about the themes of a play and then go looking and mining through that play and sometimes we would get more specific and think, “Okay. What are the words that we actually need for this section?” and would hunt for just those words. So it was a real mix of things.

I will say that a lot of the scenes worked hand-in-hand. We knew what the scene needed to be and the language would spawn from that and sometimes we knew what the language needed to be and the scene would be shaped around it.

So it’s definitely not for the faint of heart. But if you love something enough going in—weirdly, writing that part of the script was not unlike, in some ways, editing a film. You collect all the butterflies you can collect when you’re on-set and shooting. You’re this butterfly gatherer. And then you have these beautiful things to build the story from. It was a little bit like that. There was a symbiosis between the process of writing the script and shooting it.

And you get to inject some hilarious retorts with Liv insulting the psychiatrists. It’s great.

Thanks. Yeah. The insults are some of our favorite stuff to do. That’s the stuff that stuck around—that the whole team still uses. [Laughter]

Continuing with the psychiatrists: I thought the way you wrote them was really interesting. They always have Olivia’s health in mind despite the reality that they’ve imprisoned her. There’s a scene where they’re desperately trying to come up with a reason not to move her to the top floor. Films like this sometimes try to create a villain, but you didn’t. How important was it to give them that complexity?

Thank you so much for seeing that. I really appreciate it. That was really important to us both as writers and to me as the director.

Villains can be a delight in storytelling. They can be a joy. But I think when we’re talking about something—it didn’t interest me in this case to villainize anything or anyone. And certainly not the mental health systems or the people that commit to it. I did a ton of research before we wrote the screenplay. I went and talked to psychologists and neurologists. We had advisors on the script. I got to go to psychiatric institutions, see how they worked, and talk to the practitioners there. And without exception, everyone I spoke with—they all came for the right reason. They all wanted to help. They wanted to do good. They wanted to heal. Then the complexity of what happens within those systems—lack of money, lack of time, lack of resources, lack of the need for safety, and these long hours they’re working—it burns them out. They’re fighting this incredible uphill battle, but they really do want to heal and help and protect.

They’re all fascinated and interested in the beauty of the mind also. Or many, many of them are. But Liv is an enigma—and it worked on a micro level and a macro level. It was really important that they were trying to help her, but do we as a society have the skill-set to recognize what we’re seeing and to guide and protect the discussion and the life of people who are “othered.” By it’s very nature, someone who has been “othered” by society is being identified as a threat in some way, right? So how do we then take what’s important—we have to live as a society, we have to have agreements around how things work. But how do we take that situation and make it inclusive? There are ways to do this, but it’s very hard when you’re confronted with something that’s extremely different. And in Liv’s case: she explodes once she gets to the psychiatric hospital. Her need becomes huge and that can be threatening as well. So it was really important to me that we weren’t villainizing anyone.

And to this day people watch the film—and I hope it continues—and have all kinds of responses at the end about whether Liv belongs there or doesn’t belong there. Were the doctors right in the way they went about things? Should they have handled things differently? What alternative options were there? There are all these questions and I don’t have answers for them. I have my opinion, but I don’t have answers. I’m really grateful for that.

I worked with the actors that were playing those roles: Danny Burstein and David Furr, who are both Tony-nominated, amazing New York talents, and Allison Mackie. I talked to all of them about that idea. We worked on making sure that they were using everything they had. Their characters were using their entire skill-set. It’s just possible those skill-sets are exclusive and shut people out.

And what about Olivia as far as building her character and creating her psychology? How did you go about that?

When I went in to perform the role of Liv for the screenplay, for the film, I had only experienced her from the time that she starts speaking Shakespeare. I had not experienced her silence because the play took place after she had started speaking. I knew that directing would be everything and I wouldn’t have time to spend on acting at that point. I needed to do that work in advance. Before pre-production and before I had my crew and needed to focus on the actors and my collaborators.

So I went to an island off the coast of Maine and lived there for four weeks without speaking to see what that experience was like. I didn’t use language. I didn’t write. I kind of used gestures and interacted with the community. I had ideas of why Liv would be silent or what it was like to live as a silent human being and wanted to know if it was actually possible—if someone could do this with no language, no sign language. Could someone interact with a community in a way that allowed them to exist? It was incredible to find out that in certain circumstances it seems that it was possible. In this island community in particular because there are these closed communities that both respect each other’s privacy and idiosyncrasies out of necessity by being in this small space, but also depend on each other and protect each other.

I went every day and ate with the fishermen—it was largely a fishing island—in the one general store where they had lunch around 10:00 or 11:00 most mornings. I would go in and eat with them and they never asked why I didn’t speak. There was never a question around it. I was just allowed to be there and included in the circle. When I interacted with visitors or tourists—they wanted to know why. They would ask. They would need a reason. But the island residents themselves didn’t.

My experience of that journey started with these intellectual ideas and then it was very frightening to be alone on an island with no way to communicate or ask for anything: directions, assistance, get what you need. Those options aren’t available. It felt very selfish because I couldn’t offer help to people even though I could. If someone asked me for directions. If someone asked me for assistance that they needed verbally—I was capable of it, but I didn’t give it because I needed to understand why someone would make that choice.

It turned into this deeper understanding of how connected we all are. That so much of our connection happens under the surface of what we’re saying. The idea of allowing space for that can be pretty exciting. Suddenly people were coming up and sharing secrets and private memories and things I suppose they found someone who wasn’t speaking to be open to or available—or perhaps they felt their secrets were hidden, I don’t know. It was a very, very moving experience.

And of course this is not the same as someone who physically cannot speak. That ability was there for me, so there’s no way I could understand that experience. This was just my effort to investigate more deeply where Liv might have been coming from in the course of the film.

There was one instance where I was hiking and I passed this mother and daughter and they said, “Oh. There’s a man up ahead and he’s having a little bit of trouble, but if you just go around him you won’t have to worry about him.” I nodded and went on. It was a very difficult path with rungs and ladders and extremely hard to climb—kind of closer to bouldering. And I found this middle-aged man buried in the corner of this tiny little ledge, sweating, his head buried in his arms. I couldn’t go around him. I didn’t know what to do. So I put my hand on his shoulder and he said—I think he thought I was his wife or daughter—”Just leave me alone. Just leave me alone. I just need a minute.” He was so angry.

So I waited and he didn’t move. After a while I put my hand on his shoulder again and he said, “Just give me a minute” and he turned and looked at me and said, “Oh. I’m so sorry. I thought you were someone else.” And then he started asking me questions, “Do you know how long this path is? Do you know …” And I just nodded. I kept my hand on his shoulder and eventually he asked, “Will you hike the rest of the way up underneath me? And catch me if I fall?” I could never have stopped him from falling. He was heavier than I was, but I nodded “Yes” and climbed incredibly slowly up the rest of the climb under this man, helping him up the path.

At the top his wife and daughter joined us and hugged me and left. And then two days later I met them again on a path and they treated me like I was family. They said, “Oh my God, it’s our angel.” And he said, “I never knew”—and still I’m not speaking—”I never knew that you weren’t speaking. My wife and daughter told me afterwards. I thought that maybe you were an angel, literally an angel and not an actual human being, and you had come to help me up this mountain. We told everyone about you. This angel that’s out on the mountains helping people.” I just thought what an incredible thing because I think if I had spoken, he couldn’t have been vulnerable enough to ask me for the help that he needed.

Anyway. Some of that led to the film and how we ended up here.

Definitely. Because watching the film—when Olivia doesn’t speak, everyone is kind of okay with it. The moment that she says a word in a “strange” way, that’s when everyone is like, “Oh my God. We can fix her.”

Yes! Yes. That’s wonderfully said. I agree. People want reasons. But beyond the reasons, there’s a comfort in the story of The Sounding and also in life—there’s a comfort with the silence. There isn’t a comfort with speaking up in a way that is unique. And that probably brings us back to your first question about how does the film resonate stronger now than it did even when it was made. We’re full circle now.

Any new projects you’re working on now that we should be on the lookout for or expect in the near future?

Sure. Expect is a question—I mean who knows at this point how things go? I have three television projects now. They’re all original projects. One of them is based on my own experience working with freelance news crews in conflict zones, but it’s fiction. That went to IFP Project Forum.

I have a dramedy that’s called On the Outs that is, again, kind of embracing—people who watched The Sounding will understand it was created by the same person although the tone is extremely different. It’s embracing the idea of the mental health fringe and “otherness” from the perspective of the human that’s living that. And that was given a wonderful award at Tribeca.

And I have what I’m calling a tramedy called Flawless that I wrote with my co-writer Deborah Rayne. We call it a feminist fairytale and it’s a sort of social satire about what happens if all of the fairytale princesses lived a day in New York City and got tired of the narrative they were stuck in. And then what happens to the princes all floating around without a partner.

So it’s all television at the moment. I have a film script, but it’s not something I’m ready to talk about yet. Maybe I will be soon.

The Sounding is now available digitally.