If you told people in 1967 that Andy Warhol’s house band just released one of the most revered rock albums of all-time, they would ask what they’re called, and when you told them they would laugh. As far as the public was concerned, there were a hundred acts capable of that historical success in the ‘60s, and none were called the Velvet Underground (or Nico).

To a certain extent they would be right. It would be another decade before the banana-adorned The Velvet Underground & Nico would have its pop cultural comeuppance and over half a century before the glam avant-garde group would receive definitive documentary treatment by one of the best living filmmakers. But as history and said doc have proven, we would have the last laugh in that exchange.

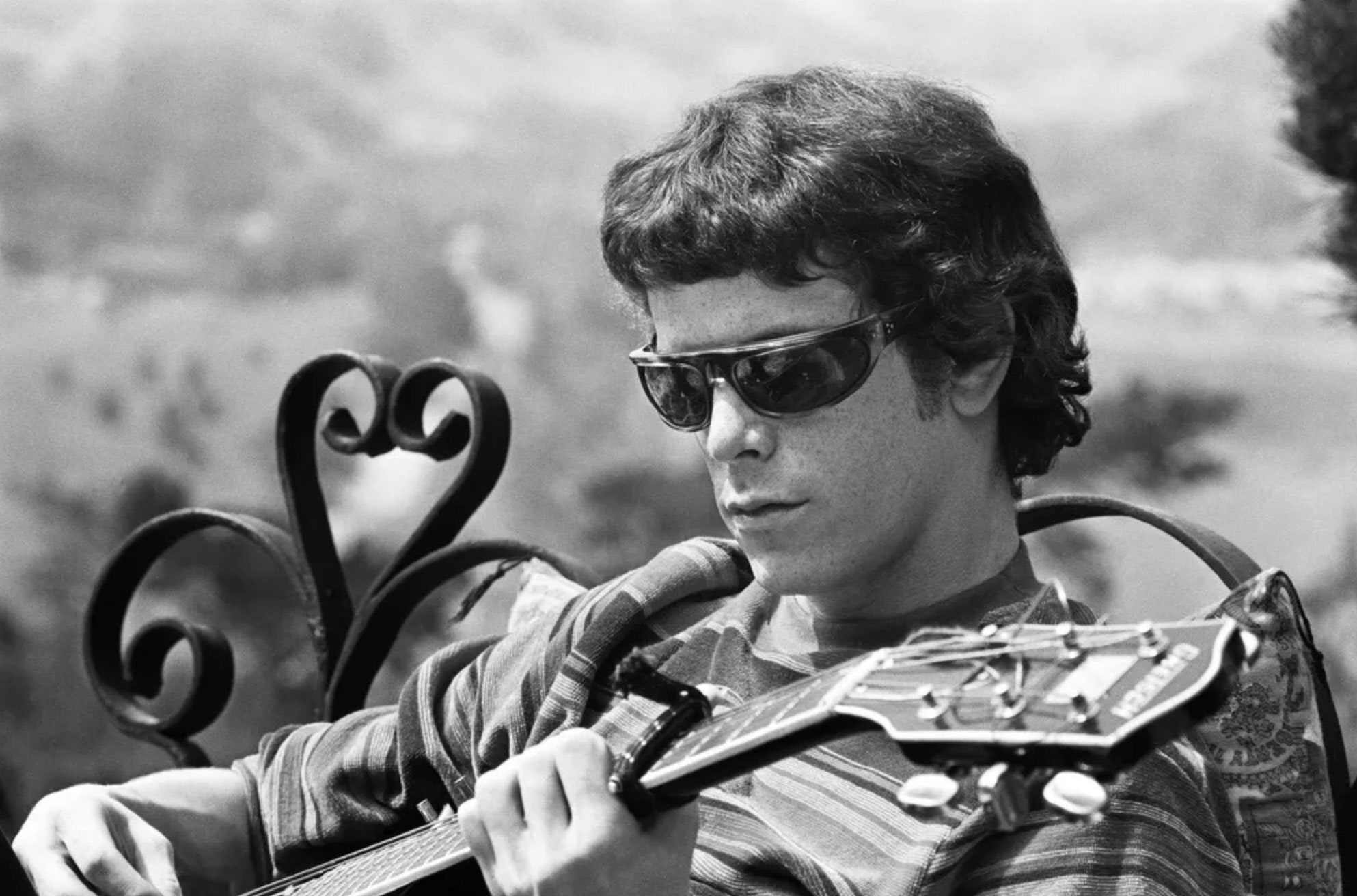

The arresting mood of writer-director Todd Haynes’s The Velvet Underground––his first feature documentary but far from his first foray into music––can be summed up in two pieces of art you might already know. First, “Venus in Furs,” the Bohemian fourth track off the group’s 1967 debut, known for its lyrical sadomasochistic provocation and slow, noisy instrumentation, courtesy of John Cale’s droning viola and Lou Reed’s innovative ostrich guitar (all strings tuned to the same note). The cacophony of sound bursts onto the scene sans introduction, establishing pace and tone.

The dark, hypnotic music spawns the film from nothing, much as the group suddenly surfaced from the unknown of the underground following Reed’s solo success in the ‘70s. The track plays over the dizzying gold title card and returns more often than any other, acting more like a thematically harmonious score than something pulled from the discography. It grounds Haynes’s doc in the lavish aural monotony on which this band was founded.

The second, equally repetitive mood-defining piece is Andy Warhol’s “Screen Tests,” a series of short films––played properly in 16 frames per second to create aesthetic dissonance––in which subjects stare as unblinkingly as possible into the camera for a few minutes. Using only a small portion of the frame’s center, Haynes employs a split-screen function that loops Reed’s screen test on the right side and archival footage chronicling his life on the left.

In time, Reed’s staring face burns out and starts over again on the left, where it eventually blues out before returning to the other side; Cale’s screen test is used similarly. It’s incredibly affecting. When else are we given the opportunity to stare into an artist’s soul while we learn about their lives? Some might find the technique, and the rest of Haynes’s direction, uninspired, but any such critique should be lodged at the band itself.

In essence, the choice communicates his approach in telling the Velvet Underground’s story—to reflect the singular art of the group, not to achieve the total comprehension of an encyclopedic entry. Cale was known for wanting to hold one note and listen to all the variations, beauties, and intricacies within, like a riff sustained for the duration of a track. Haynes aims to do the same, visually, with his subjects.

Lead guitarist Sterling Morrison and drummer Maureen/Moe Tucker don’t have Warhol films to their faces, so their sections are split with other archival footage and, in Tucker’s case, a present-day interview. Cale, the only other living member of the original four, also talks to us in the present. While Tucker and Morrison were vital to the group’s sound, Cale and Reed get the most attention because they’re most responsible for the Velvet Underground’s pioneering qualities. Reed wrote wild songs and talk-sang them unlike anyone else; Cale brought natural harmonics and an avant-garde, La Monte-esque sense of extended time yet unheard in the pop-rock arena.

Haynes leaves interpretive excavation up to the impressive zoo of firsthand talking heads: filmmaker and friend Jonas Mekas, film critic and Warhol club staple Amy Taubin, and short-lived late-band members whose involvement was borne from the turmoil that preceded them. The same folks, in concert with audio recordings of the deceased, detail delicious inside scoops.

They talk at length about the New York City Ludlow St. apartment that led to early alternate versions of the group, like the Primitives and the Dream Syndicate. They tell of how the Velvet Underground played “Heroin” in their audition at the Factory, shattering through the elegance most Factory acts carried. We learn they initially disliked Nico because she couldn’t hold pitch, and that Warhol’s presence alone in the studio made it possible for them to record anything they wanted.

Haynes traces the amphetamine underbelly of the band once distilled into White Light/White Heat, a triumph of Cale’s experimental mind and Reed’s mastery of lyrical storytelling that had absolutely no commercial value and sold as such. We learn how Reed got rid of Warhol and Cale; how Morrison left, Tucker suffered, and Reed finally took off on his own. But Haynes gives us a restorative coda in Reed’s rehabilitation, complete with audio of Reed talking about reconnecting with everyone and lovely footage of them hanging out.

It isn’t the most entertaining version of a Velvet Underground documentary, but it’s the truest to the group. Haynes hones in on character and new elements they brought to the table which, like elements of modern art, are best captured through philosophies and conceptual understanding, as they are here. Ultimately The Velvet Underground is evidence of an ever-crystallizing cinematic truth: give a great director some cash and archival access to his favorite band, and you’ve got a winner.

The Velvet Underground premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and will be released on October 15 in theaters and on Apple TV+.