In the same way that keeping your top five movies on-hand can save a not-insignificant amount of time and brainpower over the course of one’s life, it’s just as useful to have an answer ready for questions such as: what makes you like movies so much, or even why are movies important? In such moments I tend to take the Ebert line that film, at its best, is an empathy machine, a way of experiencing someone else’s reality for a short while, to see how it might feel to walk in another person’s shoes. Like a widowed housewife in 1950s New England, say; or an elderly couple visiting their kids in Tokyo; or, in the case of this excellent naturalistic debut from Lukas Dhont, a 16-year-old transgender girl awaiting the operation that will complete — in her eyes — her physical transition.

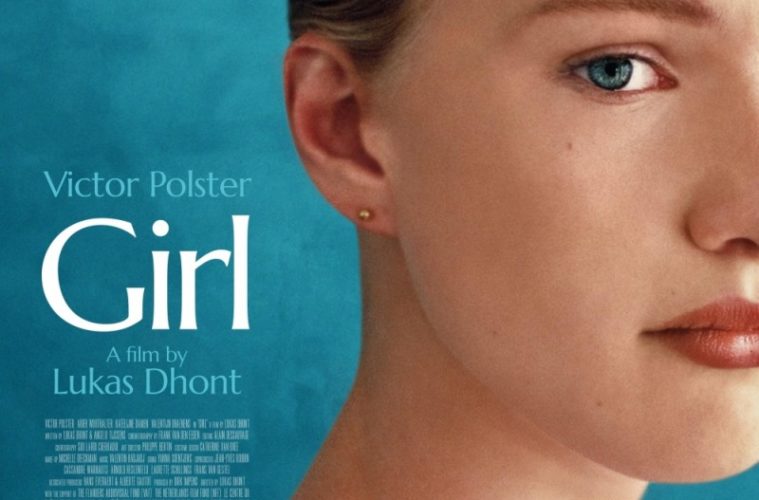

Cisgender actor Victor Polster plays Lara, a teenage girl living in an apartment in Brussels with her father and younger brother. She has just transferred to a new school where she dreams of becoming a ballerina. Lara was, however, born with a male body, so she has been undergoing hormone treatments while eagerly awaiting confirmation for a sex-reassignment operation. The people in her life, for the most part, are reassuringly supportive, if understandably inexperienced. On her first day, Lara’s teacher asks her to close her eyes so that the other girls in the class might have the chance to raise their hand if they feel uncomfortable with Lara using the same changing room. It is not the most comfortable moment, but the fact that she is made aware that the vote is even happening suggests an effort for inclusion and transparency. This is not ideal, Dhont seems to be saying, but society might just need a little time to learn by doing.

To Girl’s great credit, the director makes a point of never really putting Lara in any of the situations we have come to expect from films dealing with transgender experiences. We hear no heckles and we see almost no prejudice, at least not in the way we might have a few years ago. Girl is a film that wishes to show that her situation, existential in many ways, is surely hard enough as it is. Lara has to face one true moment of humiliation involving the girls in her dance group (who are welcoming and supportive for the most part) but it ultimately comes off as unmalicious, more a case of teens being teens. Indeed, growing up is a tricky enough time no matter what lens you see it through.

This effort to show Lara’s struggle like a coming-of-age story is what sets Girl apart. Dhont fleshes out his story with little growing-up moments everyone can relate to: the lunchroom on the first day of school, a first sexual encounter, the distance young people find with parents in those years, etc. The most moving and informative of these moments arise during Lara’s discussions with her councillor (a calming Valentijn Dhaenens), who asks her questions about who she might fancy in her class and whether or not she believes her upcoming operation or, more accurately, the skin she lives in ultimately defines who she is — the film’s key theme. Lara’s ballet class offers a distilled version of this very theme, as she tapes back her genitals and puts herself through physical torture in order to make it into a production, a goal she seems to feel will validate her transition.

It makes you wonder why we’ve had to wait so long for a film such as Girl (even the title, in its simplicity, suggests a blueprint others might follow). You would be a fool to deny Sebastian Leilo’s A Fantastic Woman any of the attention it has received, though I would argue it is more an important movie than a great one and preaches just a little too much to the choir to be regarded as universal. More significantly still, Leilo relied too often on incidents of prejudice and hate to tickle the viewer’s most passionate emotional responses. Girl (an important film and a great one) channels love and compassion and is incomparably more powerful for it.

Girl premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. Find more of our festival coverage here.