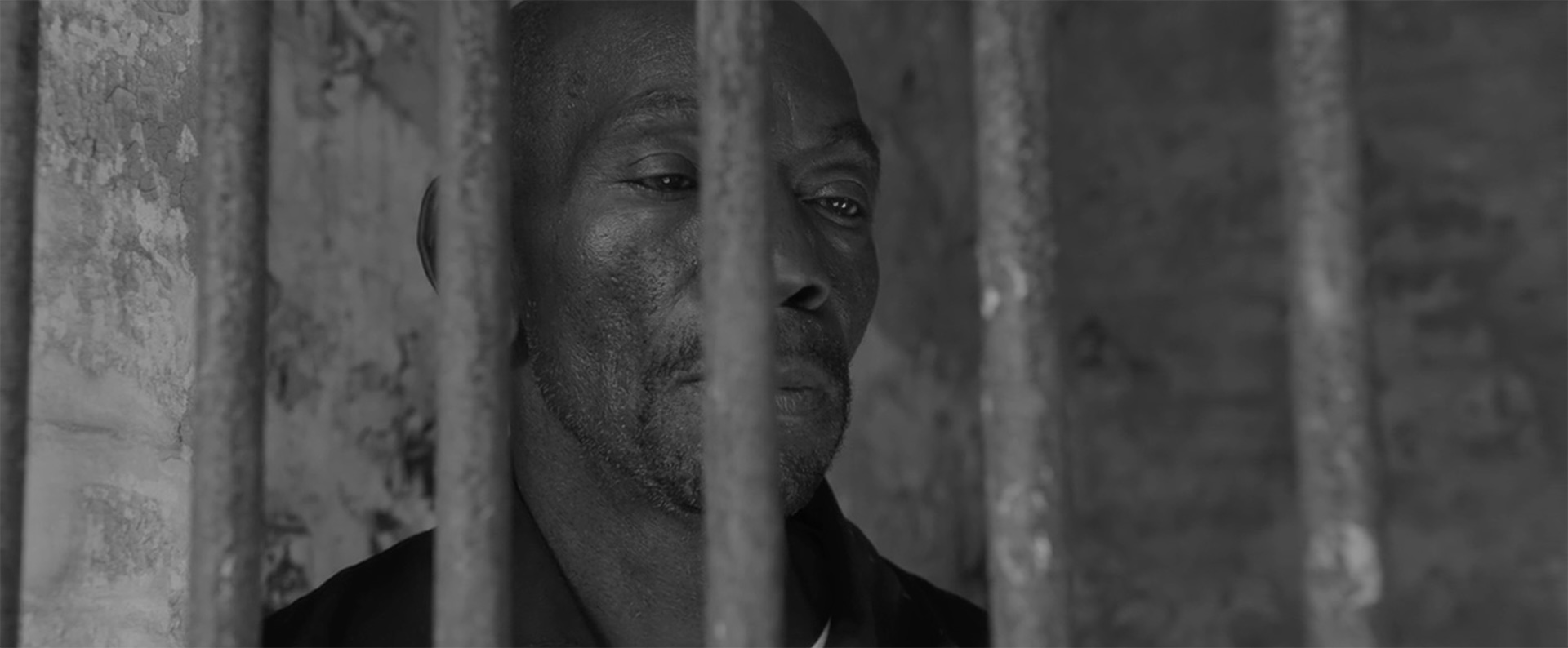

More than just a documentary detailing the circumstances surrounding Rickey Jackson’s 1975 conviction for a murder he did not commit, Matt Waldeck’s Lovely Jackson is a memoir granting its subject ability to exorcize his demons through a first-hand, in-his-own-words reckoning with the experience. The result creates an emotional juxtaposition that goes beyond simply narrating reenactments—it enlists Rickey to both play himself and stand watch as Mario Beverly plays the memory of the 18-year-old man he was upon entering Mansfield Reformatory, the actual prison he inhabited before he was sent to death row for eight months. The exercise thus exists somewhere between your conventional true-crime drama dissecting facts via interview and the heightened, visceral approach of Robert Greene’s Procession.

This approach is a necessary one, considering Jackson spent 39 years behind bars. 39 years surviving day-by-day as each night brought both the sobering realization of everything he lost and the dream-fueled approximation of what it might have been were he free. And all the while he plays back the words his mother told him: “Don’t let yourself be a prisoner.” She said he was going in Rickey Jackson and that he had to fight to ensure he left Rickey Jackson. Those words sought to keep him strong—and ultimately did after the state of Ohio voted the death penalty unconstitutional mere months before his execution date—but first they felt somewhat empty. Because hope isn’t easy for the hopeless. Neither is truth.

That’s what Jackson had on his side, though. Despite everything (including multiple parole boards all but telling him they’d set him free if he admitted guilt), Rickey remained steadfast. Even when two decades passed without a visit from friends or family, he refused to give into temptation and let the system take his truth along with his freedom. While that might be enough in a perfect world, ours unfortunately demands more. Years of letters desperately trying to find one person willing to fight with him. Years of tracking down the now-50-year-old witness (Edward Vernon) whose coerced testimony as a 12-year-old was the only “evidence” linking Rickey to the crime. And, even then, courage to risk never having another chance at release to seek a complete exoneration.

Before getting there we must first enter his headspace to understand how he could keep going. There’s the luck of finding fellow inmates that taught him how not to fall prey to the dog-eat-dog nature so many others do. His mother’s words helped. His resolve to stay positive allowed him to live the mantra of “get to tomorrow” rather than succumb to today. Rickey isn’t one to sugarcoat things, either—he speaks about time twisting in on itself or the violence and murder that he witnessed while inside. It’s no surprise we eventually see him onstage at a TED Talk during a brief post-prison montage; the film sometimes plays like a one-man motivational speech about perseverance, forgiveness, and second chances.

More than just him, however, we also get to hear from the other players in his story. There are the lawyers who mount the case for a retrial. The teenager who was in the store when Harold J. Franks was murdered and testified that the shooter wasn’t a local (and definitely wasn’t Jackson, whom she knew) to no avail when the police and court worked in lockstep to put Rickey away from day one. And, of course, Vernon himself: the boy whose words stole Jackson’s life and the man whose words gave it back. His inclusion isn’t malicious, though. He isn’t the villain and Waldeck knows that pretending he is only helps ignore the system that used him, ultimately destroying his own life via debilitating guilt.

This is possible because Rickey never lost his humanity. That’s its own miracle beyond the crazy strokes of fate that led him here today. Despite all the talk of steeling himself emotionally from the highs and lows of his plight, he never hardened himself beyond repair. We watch him go through the motions of playacting the jobs he had in jail, describing them with a fond appreciation rather than revulsion since they helped him pass the time. (Thankful, too, because their existence is to prepare inmates for a return to life outside—something his death sentence and subsequent life sentence didn’t promise.) We still see the immovable trauma in his tearful descriptions of memories and nightmares he can’t shake, but there’s also an indefatigable light that burns bright.

So while it seems Lovely Jackson should end around the 70-minute mark with Rickey’s release (as black-and-white turns color), that’s only the start of his happily-after-ever. He might be a lovely man, but the title is for his daughter. We see her in glimpses—fantasies of fatherhood during prison nights and sitting on his lap while stoically posing in an electric chair—but it’s not until later that we get to meet her in the flesh as the culmination of this horrific yet inspiring tale of rebirth. A father at 62 after everything he endured? You can’t make this stuff up. But listening to and seeing inside Jackson’s psyche as he contextualizes, reconciles, and remembers proves he deserves every good thing that comes his way.

Lovely Jackson screened at the Buffalo International Film Festival.