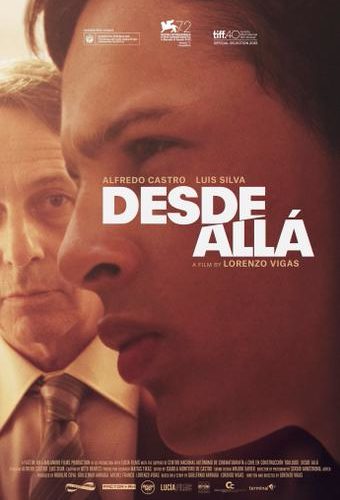

Proving yet again that festival juries don’t read the trades or pay attention to chatter, the Golden Lion of the 72nd Venice Film Festival was presented to the Venezuelan drama From Afar, a film that screened relatively late at the fest, when general opinion on the Lido seemed to have settled on this being a race between some other titles. In a discerning and gutsy move, the star-studded jury chaired by Alfonso Cuarón decided to recognize the achievement of writer-director Lorenzo Vigas’ debut feature over some perhaps higher-profile pictures from established masters. It’s gutsy because this film tells a moving if deeply unpleasant story with a significant ick factor that’s going to put many people off. It’s discerning because, as contained and particular as the film’s subject matter and as unassuming as its approach, From Afar delivers an incisive, poignant, surgically precise character study that deals a fatal blow in one crisp, clean stab.

We first meet Armando (Alfredo Castro), a middle-aged dentures shop owner who finds release for his closeted urges by bringing home young men he picks up from the streets. Not five minutes into the film we already see him fervently masturbating to the sight of a teenage boy’s exposed behind. There doesn’t seem to be any physical contact involved and the brief rendezvous goes down consensually. Yet the hushed atmosphere, the cash exchange and the marked age difference between the two participants, underlined by close-ups of one’s wrinkled face and the other’s babyishly smooth skin, give the whole episode a sleazy, repellent air.

Judging from Armando’s nonchalant demeanor and practiced orchestration of the meeting, you get the idea he’s been doing this for a while. But nothing has prepared him for Elder (Luis Silva), a street kid with a fiery temper who backs down from a deal, turns to assault and rob the older man before fleeing his apartment. It’s no surprise that Armando doesn’t report the incident to the police and silently stomachs the injuries he suffered. Things get interesting, however, when he seeks out Elder again and, without a hint of anger or fear, willingly offers to pay this violent, unreliable person a second time, thereby setting in motion a chain of events none of them could have expected.

Written with a forthrightness that cuts through caution and shame, Vigas’ screenplay allows a highly unconventional relationship to run its course. The two main characters are anything but sanitized, amply demonstrating their least appealing qualities while trapped in some desolate far reaches of the human psyche. There are no labels put on the many emotional gray areas they go through. Instead, we simply witness how out of an animalistic, mutually exploitative arrangement grows something approaching tenderness, which in turn triggers reactions in both of them as subtle as they are devastating. Through it all, Vigas’ writing remains non-judgmental and keenly observant. He doesn’t attempt to explain everything with words, but the raw honesty of his voice compels every step along the way.

Vigas the director also knows to keep the ambiguity alive, playing with composition, depth and distance in a way that emphasizes the gap between the protagonists. Armando is often seen from the back, looking out onto a pool of potential prey, his estranged, supposedly abusive father, or just this mysterious boy who might be sleeping right in front of him, yet could not be more remote, heartbreakingly unknowable. In the scene where Elder first introduces Armando to his family and friends at a dance, the camera traces the wondering looks of different parties from across the floor, communicating with little verbal help a tension simmering in the room as curiosity, attraction, jealousy and everything in between slowly take control. Like the rest of the film, the staging here is economical, the styling modest, but the immediacy and effectiveness of the visual language are unmistakable.

Both leads are excellent. After a brilliant turn as a pedophile priest in Pablo Larraín’s Berlinale-winner El Club (The Club) earlier this year, Castro dazzles again with the complex portrayal of someone harboring a secret. Restrained, alert, camouflaged by an exterior of prudence and indifference but desperate from a mind coarsened beyond repair, Armando is an exceptional creation that repulses, captivates and mystifies. On paper it would take some persuasion to buy a character of such contradictions and obscure motivations, but Castro’s face, at times hardened by despair, at others softened by longing, informs you so much of a chronically lonely person that, on an intuitive level, everything falls into place. Newcomer Silva brings an unpolished explosiveness to the picture, which plays off Castro’s calculated placidity tremendously.

Powered by a sea of suppressed, unreciprocated feelings, From Afar beautifully describes the mechanisms of desire in what begins as an almost-love story that ends up something tragically different. It might not be the most ambitious or technically achieved film of the Venice competition line-up this year, but it certainly cuts closest to heart, leaving behind the most jagged tear.

From Afar premiered at the Venice Film Festival and opens on June 10.