For its combination of rocking performances from famous musicians (the line-up included St. Vincent, tUnE-yArDs, Nelly Furtado, and Byrne himself), the dazzling work of athletic, often high school-aged color guard teams (those flag- and baton- and rifle-waving types who perform synchronized dance routines), and the compelling success story that comes with their meeting in an arena — to say nothing of the presence / brand carried by the show’s mastermind, David Byrne — last year’s Contemporary Color tour is an exceedingly film-friendly show, a visual-aural presentation the likes of which most directors would be thrilled to have placed before them. That also makes it potentially dangerous territory: if the glut of bland concert movies are any indication, many of those same directors might be tempted to do little except observe, essentially having their subjects meet them 70% of the way.

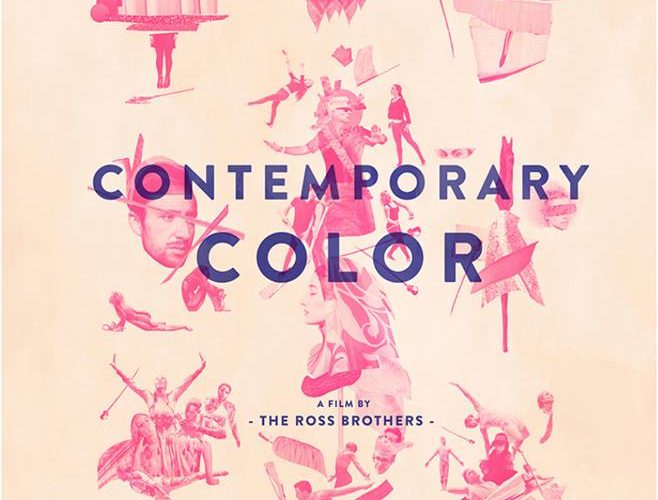

It’s important to note this when speaking of, and ultimately complimenting, filmmakers Bill Ross IV and Turner Ross, on their own Contemporary Color, a feature version of this event. Armed with full access, several camera operators — including indie darling DP Sean Price Williams, as well as directors Robert Greene (Kate Plays Christine, Actress) and Amanda Wilder (Approaching the Elephant) – and some vision of how to shape the obvious into the bold, they’ve created an experience that captures (and may even supersede) the fertile ground upon which it’s been built. In its formal inventiveness and compassion, Contemporary Color moves well past the boundaries of “concert movie.”

Not that those seeking as much would likely come away unsatisfied. The performances driving Contemporary Color, tour, are the loud and colorful center of Contemporary Color, movie, singing and twirling and doing whatever else their carefully arranged routines call for, each mostly presented in full and always played to a proper volume. But letting those figures take up the legwork doesn’t seem half enough for the Ross brothers, who take formal turns — some rather standard of the genre, some more visually explosive, and few of which are less critical than or out of step with another — that give Contemporary Color qualities that are both intimate and otherworldly.

One’s attention during specific song-and-guard turns will likely depend on how much one cares about an individual performer, yet the teams’ swirl of colors makes for a near-constant source of lavish sights. But more stimulating than that are the Ross’ (Bill IV is the credited editor) extensive use of cross-fades and superimpositions (see the below image for just a conservative example) that crush the space between musician and team, permitting intimate close-ups of a famous artist and wide shots of the up-and-comers to exist side-by-side. The movie will sometimes stack more images than I could count to create a confection of color, bodies, and music; when, for instance, St. Vincent performs, the post-production manipulation creates a vision that reminded me less of other concert movies and more of an orgiastic montage from Metropolis or wild-haired, wide-eyed glares from The Bride of Frankenstein.

There nevertheless persists some issue with regards to the how and why of this movie’s representation, one I couldn’t quite shake in moments when I wasn’t enraptured. For as much as the importance that this performance holds for many team members would be emphasized time and again via the announcers’ booming voice — e.g. that this is the final turn for many high-school outfits — and backstage footage, the movie sometimes lacks for something as essential as proper coverage of their works, be that a wider visual perspective or longer takes to emphasize the level of coordination.

If not a cure-all, one “solution” provided therein — and yet another neat device to help Contemporary Color expand past the boundaries of its ostensible genre — are the many cut-away sequences employed during performances. Call them flashbacks, fantasies, or interior monologues: one group performing in a gym as the music swells, an individual member running down a street or performing in a garage of what may very well be their childhood home, or two girls (whose friendship has been contextualized in a brief behind-the-scenes sequence) working for seemingly nobody but each other.

These can also create a lack of balance when giving participants their screen time, and yet those sequences manage to isolate and underline the young athletes’ turns in a fairly efficient way. The not-inconsiderable length of time this movie spends backstage and harnessing its performers’ pre- and post-show energy serves an efficient extension of that emotion by building up towards or coming off a curtain call, and thus part and parcel of its satisfaction.

Contemporary Color often plays as a snapshot of one moment in time — e.g. brief footage of an empty room’s TV broadcasting news of marriage equality passing in the U.S., one quiet moment of the world passing by that’s later externalized in a performance from Byrne and St. Vincent — as much as an apotheosis of effort for its young participants, for whom this may have passed as quickly as it began. But just as none of the involved players are likely to forget that moment for the rest of their lives, this film, in its displays and occasional transcendence, ensures their efforts and passions live forever.

Contemporary Color premiered at the 2016 Tribeca Film Festival and opens on March 1st.