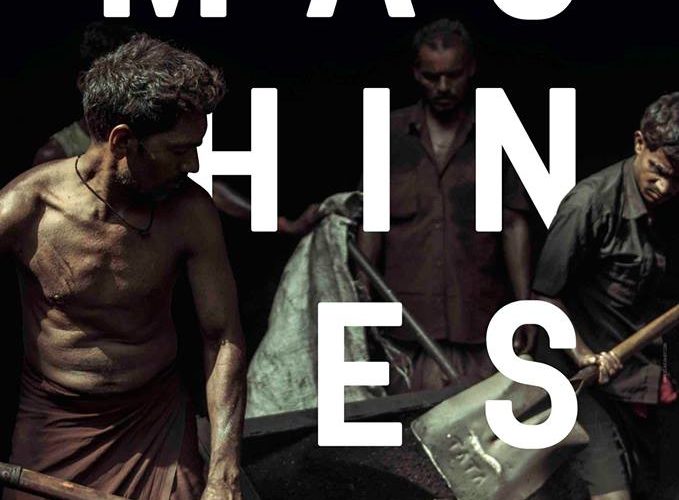

The most pointed question asked by Rahul Jain‘s documentary Machines comes from the camera. By showing us the gigantic textile spools, looms, and washers with only their rhythmic clanks, booms, and bangs opposite the Indian workers applying dyes, mixing chemicals, and ensuring there are no jams to the same sounds, we must wonder which are the “machines” of the title. This is an assembly line of ancient metal units kept moving by a revolving door of migrant workers that start at the age of ten to learn everything in youth and become irreplaceable by their thirtieth anniversary. The entire whole proves to be the machinery of an unseen man sitting in his office with a bank of surveillance screens flickering while he presses buttons on his phone.

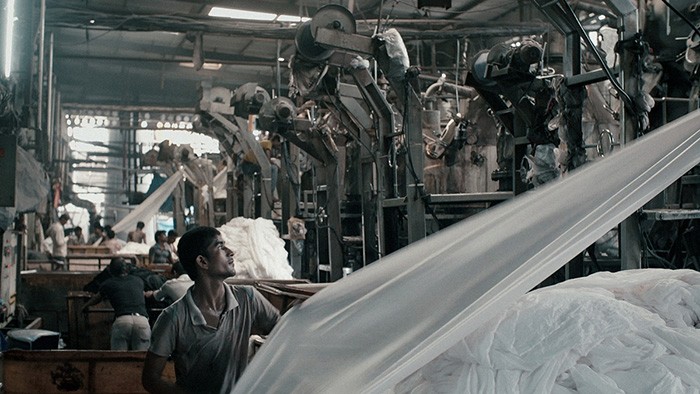

It’s an astonishing experience to push through the dark alleys between rows of massive apparatuses working tirelessly, navigating around the men caught in loops of muscle memory for twelve-hour shifts with sometimes only an hour respite in between. Rodrigo Trejo Villanueva‘s Sundance award-winning cinematography is glorious as his camera puts us into the process as voyeur: soaring down walkways, ducking beneath sheaths of fabric, and following from the ground behind heavy carts wheeled to who knows where as the pops and crackles of industry pulse in our ears. Besides a foreman telling his men to stand straight for the camera, the first fifteen minutes are devoid of words. And yet it’s as though we’re hearing a story unfold nonetheless. One of struggle, perseverance, and ultimately despair.

Jain does eventually break from the fly-on-the-wall approach at times, giving certain workers a one-on-one to speak freely about their experience. He lets them talk without injecting his own voice to push content or context this way or the other. One gentleman makes it clear that he isn’t being exploited, that whatever this film may become it shouldn’t be an exposé. This worker has taken out loans to get to work. We learn that many do. When droughts are putting farmers in debt around the country, they must pay to travel upwards of thirty-six hours to industrial parks like this Gujarat-set chemical and dye factory to earn their three American dollars per twelve-hour shift wage. This man speaks about what he does because he has no other choice.

We hear from a contractor who takes care of his men with gifts of rupees to ensure they don’t start unions—something another minion to the capitalistic dream says never work anyway because the union leader is fingered and subsequently killed. We hear from the owner who never goes on the floor, a man who fondly remembers decades past when employees made much less and weren’t so complacent because their heads were in a vice tighter than the one wielded now. And we hear from an outspoken champion of the people not asking for assistance from Jain or telling him what they need. This man merely asks, “Do you want to save us? Then tell us what to do and we will.” Their situation’s futility is unavoidable.

So the footage carries on. We move from a silkscreen station pushing forth white linen until it’s covered by multiple colors and patterns to the chemical containers carefully weighed, mixed, and measured. Two men are shown as they combine pigment and base with the effortlessly timed motion of a spoon—a system seemingly so arbitrary and yet resulting in a consistency that rivals a Pantone construction. One boy is lingered upon for minutes, his eyes initially converging into slits as though he’s feeling the fabric move between his hands without letting sight distract him before we realize he’s falling asleep. His head bobs and then jerks back up, not even a hint of embarrassment on his face when looking at the camera before doing it again.

Special pains are taken by Jain to not interfere, even when outside with workers emptying tubs of paint and refuse at the feet of young urchins seeking precious metals to scavenge and sell. The camera enters these spaces to observe. It documents the poor sanitation as it immortalizes the efficiency of skilled labor. The boss isn’t afraid of letting Jain come in because he knows he isn’t forcing these employees to do anything they don’t want to do. To him he’s providing a service, careers to sustain families he doesn’t believe half his workers care about anyway. It’s much the same when visiting India. I walked through multiple stores where employees sat at looms in rhythm without pause. Without laws forbidding such conditions, it isn’t exploitation. It’s life.

There’s a sense of awe and heartbreak as a result. To watch as this delicate cloth escapes such heavy, oppressive machinery is a brilliant juxtaposition especially when you also include the human aspect of soft hands and soot covered faces bridging the two aesthetics into one. We begin to feel the heat of the fire sparking onto a furnace coaxer. We begin to smell the chemicals a mixing supervisor only has a scarf to protect his respiratory system from. It’s impossible to therefore leave the film without a concrete answer to that pointed question of the camera—the experience revealing poverty as the real machine. When inequality, hunger, and destitution allow society to stand on the backs of men rather than lend helping hands, we all suffer.

Machines premiered at the Sundance Film Festival and opens on August 9.