When thinking about the Israeli army, images of badass Mossad agents covertly wreaking havoc across the world crop up. It’s a hyperbolic generalization, but that’s kind of the flavor our media delivers being that the country is such a strong defensive ally of the US. We’re to believe in their power. The problem with this, however, comes from the fact every citizen eighteen and older is conscripted to a mandatory two-year stint. No country can have a law like that and expect to receive only brawny heroes ready to lay down their lives because orders say so. It’s probably more accurate to expect the majority of enlistees to be on the exact opposite end of that idealistic spectrum. Luckily for the officers there isn’t a scarcity of thankless jobs to fill with those deemed ill-equipped for combat.

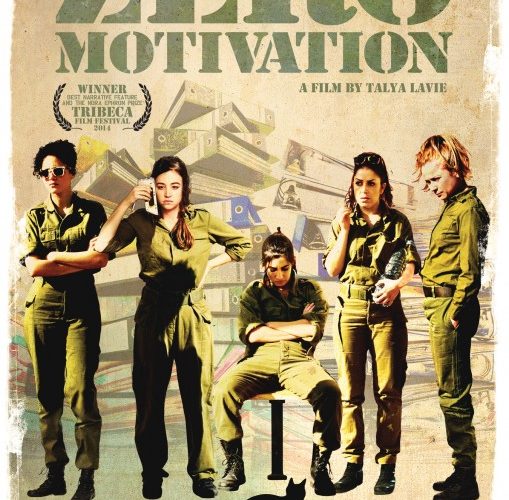

This reality ensures a mass of uniformed soldiers simply passing the time behind computers and paperwork because of their need for the government to stamp a release form and free them from servitude. Writer/director Talya Lavie was one of these poor souls dying of boredom at an administration building in the desert, biding time and hoping complacency didn’t completely destroy her. An artist earning plenty of critical acclaim already in her home country despite Zero Motivation being her debut feature (it won five Israeli Academy Awards and Tribeca’s Best Narrative Feature), it’s hardly a surprise that she’d take her experience and package its futility’s inherent humor for mass consumption. Centering on three characters stuck on a similarly sandy base, Lavie takes us through the unavoidable comedy of errors, biting irony, and unflinching takes on taboo the army provides.

Comparisons to MASH are warranted. This story is about the cogs of the machine humorously slogging through menial work no one else wants. I’ve never served in the military so it may be glib for me to make this comparison, but it’s as though these characters are participating in an unpaid internship. Their bosses barely pay attention, more games are played than papers filed, and the level of frustration is high enough to feed pranks that ultimately create more work than if everyone simply did his/her job. Lavie uses stereotypes to facilitate such a relatable environment but never belittles the authenticity of each within that façade. The same can be said about prevalent situations concerning suicide and rape. While each is portrayed with a comical aura, their severity remains and sometimes finds itself augmented by the levity.

At the forefront is Zohar (Dana Ivgy)—the most underachieving member of the entire base. She constantly plays Minesweeper, does anything possible to subvert her commanding officer Rama’s (Shani Klein) authority, and goofs off with best friend Daffi (Nelly Tagar) because the rest of the office treats her with derision. Even though the first chapter deals with a young girl in love (Yonit Tobi‘s Tehila) replacing “princess” Daffi so she may escape to the more hospitable Tel Aviv and the third focuses on Rama’s drive for promotion alongside Daffi’s fateful trajectory’s joke of a resting place, it’s Zohar who plays catalyst. It’s her actions that drive the others to move, leave, or apply themselves; her troublemaking reputation and complete indifference to reprimand ensuring everyone rises or falls while she remains forever in purgatory.

Ivgy delivers a nuanced performance despite being that ignition point by continuously displaying the sense of worthlessness we’d all feel under similar circumstances. She is given little respect, watches as the only things keeping her awake are taken away, and resigns herself to doing less than the bare minimum in hopes they’ll send her packing just so they won’t have to deal with her anymore. You can see her pain when she’s angry even if it isn’t as obvious as the disappointment towards her worn by Tagar and Klein because you relate to her wanting to appear strong despite her world crumbling down. To Lavie’s credit, however, this isn’t some fluff piece of sorority drama and jokes. There are still consequences for every action and just because Zohar is the lead doesn’t mean she’s immune to them.

This reality exposes the muddier details of conscription. There’s obvious sexism involved, an issue of safety when responsibility is given to soldiers not ready to possess it, and the inevitable ambivalence cultivated inside an institution populated by those who don’t want to be there. So while there’s a lot to laugh at, Lavie doesn’t ask us to take the mental anguish and psychological fracturing lightly. It’s funny to smirk as everyone mocks the girl unable to come to grips with sleeping in the bed of someone who killed herself, but we’re also exposed to the truth of what that means. We’re shown the meaning of friendship through it being put to the test, the fulfillment of taking pride in your work when no one else will, and the arduous process of surviving a nightmare by any means necessary.

To some it’s singing pop songs in tandem for the displeasure of everyone else; others revel in the different ways they can get away with refusing to do the one thing they must despite it being as simple as shredding papers. These girls are trying to stay sane in an insane institution run by workers counting the days until a new recruit replaces them. There’s no incentive to do a good job if you don’t plan on staying past two years and those who do are saddled with the impossible duty of motivating soldiers with one foot out the door to help their advancement. Lavie for all intents and purposes gives us American cubicle humor as transplanted to the Israeli warfront. A hilarious analogy for us, it’s a head-smacking expose of absurdity for those who’ve lived it there.

Zero Motivation opens in NYC on Wednesday, December 3rd. See the trailer above.