With so many writers and directors keen to give us a look at a future ravaged by an impending war between man and his creations, it’s always a breath of fresh air when someone decides to show the potential of an evolutionary leap towards harmony. That’s not to say Caradog W. James‘ film The Machine is devoid of violent carnage at the hands of bloodthirsty militaristic bureaucrats sitting behind desks as their employed scientists crack the code of invincible killers beholden to their every whim. Any bid for peace is born from war whether one that decimates soldiers until truce becomes a final option or one where the threat of worldwide annihilation manifests a tenuous stalemate of mutual salvation. As weaponry advances to nightmarish heights our question, “Can we control it?” must change to “Can we trust it?”

These queries are given physical representation through two characters located on a secret Ministry of Defense base in Wales. The former lies with Thomson (Denis Lawson), a by-the-numbers political villain who cares more about the damage new artificial intelligence can inflict on England’s current Cold War enemy China than its capacity to protect home. The latter remains on lead scientist Vincent’s (Toby Stephens) mind courtesy of a personal need to play God propelled by life rather than death. With a daughter caught in a perpetual state of seizure, he hopes this government work unencumbered by budgetary constraints will bring him closer to a cure. So he recruits the best and brightest, testing their AIs to find one worthy of taking that next step. Ava (Caity Lotz) proves both the victor for peace and catalyst for destruction.

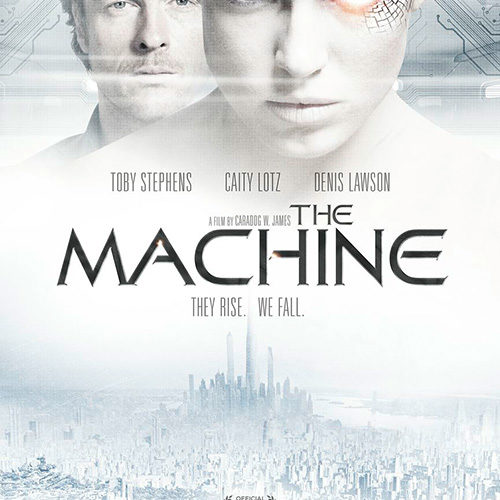

If you’ve seen the poster or trailer you’ll know Lotz also plays the titular machine, a fully formed creation made possible by mankind’s greed and hubris pushing the boundaries of morality (with seamlessly intuitive special effects). It’s a quick transition James’ writes in a way that allows for exposition to subtly inject itself into our consciousness. Who Ava is, why she created the intelligence she willfully gives to Vincent, and the future before her are rendered moot when you look beyond the surface. She is simply the newcomer for us to sponge tiny details from like her introduction to a hybrid security force consisting of brain-damaged war vets brought back to a mute consciousness through mechanical implants, their ability to converse telepathically with one another, and Thomson’s dismissal of their human beginnings as nothing more than tools for experimentation.

Ava is our conduit to look behind the curtain at what’s really going on—the last innocent piece of collateral damage Vincent can endure before he accelerates his own motives. Everyone involved has his or her own agenda that isn’t at first transparent, whether it be Thomson’s implanted head of security Suri (Pooneh Hajimohammadi), test subjects like paraplegic James (Sam Hazeldine), or the Machine herself. We sense a desire for revolution growing denser as the film goes on. We watch Vincent’s patience wear thin as his daughter is hospitalized and his creation usurped behind his back by Thomson. Tensions mount between controllers and controlees much like the impending war we hear about pitting the UK against China, each side positioning itself until confrontation can no longer be avoided. And a new question presents itself: What does it mean to be alive?

This is James’ thesis as so many forms of life are brought into the fold at differing states of consciousness and capacities for empathy and compassion. There’s Vincent’s daughter Mary (Jade Croot), a girl alive yet imprisoned within her body; the implanted soldiers given a second chance yet enslaved by their “heroes” via psychological blackmail; and the Machine, a creature with emotion, guilt, intelligence, and love that does not eat, breathe, or sleep. Are any of them less alive than the next? Flesh, hybrid, or metal—each sees what’s happening around them and adapts. Thomson sees consciousness as a threat to control while Vincent sees its autonomy as necessary for the future. After all, what is more human than survival? Unless a machine can value its own existence, can it ever value ours?

So here it is, trapped between Thomson and Vincent just as they are caught between it and each other. One hopes to prey on the Machine’s lack of “life” while the other looks to prove it’s as real as he. Consciousness and communication become the lynchpins to existence not as humans but as beings beholden to no one but themselves. We create for maximum impact and then fear a potential future where we lose control—this is the normal. James flips the conceit a bit by showing how it’s the creation’s capacity to know when to dial its strength down that should scare us. Only when it allows itself to choose which of us are worth saving does it wield unchecked power because the ones who wish to control it are generally its most dangerous adversaries.

Beyond even this level brought to life by Lawson’s stereotypical government enterprise baddie, Stephens compassionate father standing on a cliff’s edge, and Lotz’s monotone machine learning rather than mimicking lies the true commentary on our current state of affairs. While the science fiction concerning artificial intelligence and robotics thinking for themselves is present, there’s also the question of whether our reality’s constant rise and fall of alert levels, terrorist attacks, and preemptive strikes that could be construed as acts of terrorism by our victims means we’re even living ourselves. We’re only two decades removed from a time when kids could play in their front yards without risk of abduction and that domestic fear has only grown. It’s defense versus offense—Terminator 2 reappropriated killer into protector then, and The Machine looks to remind us of that lesson today.

The Machine is currently available on VOD and opens in limited release Friday, April 25th.